Artist | Martin Honert (*1953)

https://www.artist-info.com/artist/Martin-Honert

Biography

Biography

born in 1953

About the work (english / deutsch) Photo

About the work (english / deutsch) Photo

When I first saw Martin Honert's work, I immediately associated it with an image from my own childhood: "Off you go and sit down," says mother in the kitchen, "you'll get your tea in a minute." Hungry as I am, I watch her making it.

But the work we are looking at here is called Photo. The Photo on which the work is based - Martin Honert does not use it publicly - shows the family Honert, father, mother, two brothers and a sister sitting at the table. On the right in the background, where the father is sitting, there is a window through which the light comes streaming in. They seem to be doing their homework together. The mother, looking amused, casts a glance towards the father, who is engrossed in a notebook with the hint of a smile on his face. The older brother and the sister are concentrating hard on their work. Only the youngest, little Martin Honert, is gazing attentively into the camera of the photographer. In other words, in his 'spatial image', the artist has not only excluded all the other people, but even the schoolbooks and notebooks on the table, leaving only himself sitting at the table, reiterating the selfsame expression, look and pose captured on the photo.

This work is also entitled Photo because the figure and table portray the light and shadow and their transitional zones very precisely. The top of the tablecloth, for example, is relatively over-exposed in comparison to the sides hanging down, which are darker. Also, the little boy's face and his clothing on the side towards the light are painted in much lighter tones than the side in shadow.

What is remarkable about this 'spatial image' is its apparent banality. It is neither extraordinary nor exotic. Yet its imagery is so powerful that it hits us directly. We do not even have time to regard it with astonishment: we sense it almost physically. We feel the pain of remembering.

Memory is Martin Honert's theme. In each new work, he asks once again how to lend expression to the act of remembering.

Forays into the realm of memory involve a certain degree of risk and the danger of detachment from the present. After all, recollection is revealing only when it implies the present. For Martin Honert, remembering is inextricably linked with the work process. He even goes so far as to approach each new work by consciously seeking a completely new experience in handling materials. This new experience forces him to bring the properties of the material into line with the image of recollection.

In my description of this work at the beginning of the text, I did not mention the complexity of its production and the experimentation involved at each stage in the quest for ways and means of transposing photography into spatial reality. When I spoke of the way the 'spatial image' is painted, I meant painting in the fine art sense, for Martin Honert actually 'paints' a three-dimensional picture. Transposing photography into the third dimension necessarily involves the process of painting. Painting in the sense of applying a coat of paint is not an act carried out once everything else has been completed, but is in fact an added spatial dimension of the 'sculptural' concept itself.

It is important to use quotation marks here because Martin Honert does not actually regard himself as a sculptor. He creates images. Images of memory: that which has been seen as that which I have perceived in my memory or as that which has been captured in a photograph.

Foto

Als ich das Werk von Martin Honert zum ersten Mal gesehen hatte, prägte sich sogleich ein Bild aus meiner eigenen Kindheit ein: "Setz' dich mal schön hin," sagt die Mutter in der Küche, "du kriegst gleich dein Vieruhrbrot." Hungrig wie ich bin, schaue ich ihr zu wie sie es vorbereitet.

Nun heißt aber das Werk Foto. Das Foto, das dem Werk zugrunde liegt - Martin Honert macht davon nicht öffentlich Gebrauch - zeigt die Familie Honert, Vater, Mutter, die beiden Brüder und die Schwester am Tisch sitzend. Rechts im Hintergrund, dort wo der Vater sitzt, befindet sich ein Fenster mit starkem Lichteinfall. Es scheint, als ob gemeinsam Schulaufgaben bewältigt werden. Die Mutter schaut belustigt zum Vater hinüber, der seinerseits, in ein Heft vertieft, ein feines Lächeln zeigt. Der ältere Bruder und die Schwester sind angestrengt mit ihren Arbeiten beschäftigt. Einzig der jüngste, der kleine Martin Honert, blickt aufmerksam in die Kamera des Fotografen.

Somit hat der Künstler für sein "räumliches Bild" alle anderen Personen, aber auch die auf dem Tisch liegenden Schulhefte ausgeblendet und nur noch sich selbst am Tisch sitzend mit demselben Blick, demselben Ausdruck und derselben Haltung wie nachträglich im Werk festgehalten.

Foto heißt diese Arbeit aber auch deshalb, weil das "räumliche Bild" in der Bemalung von Figur und Tisch den Lichteinfall und das Schattenspiel mitsamt den Übergangszonen sehr genau berücksichtigt. So zeigt die Tischdecke eine Überblendung im Unterschied zu den dunkleren, seitlich herunterfallenden Partien. Und die dem Licht zugewandte Gesichtshälfte des kleinen Jungen wie auch seine Kleidung sind sehr viel heller gemalt als deren Schattenseite.

Das bemerkenswerte an diesem "räumlichen Bild" ist seine Selbstverständlichkeit. Es ist weder außergewöhnlich noch exotisch. Die Bildhaftigkeit ist so stark, daß man betroffen ist. Man hat nicht mal Zeit, es staunend zu betrachten: Man nimmt es sogleich im eigenen Körper wahr. Ein Schmerz der Erinnerung macht sich bemerkbar.

Erinnerung ist das Thema von Martin Honert. Für den Künstler stellt sich von Werk zu Werk die Frage neu, wie dieser Erinnerung Ausdruck zu geben ist.

Sich in die Erinnerungen zu begeben ist nicht ungefährlich, denn man kann sich von der Gegenwart abkoppeln. Erinnerung ist nur dann aufschlußreich, wenn sie den Standpunkt der Gegenwart impliziert. Für Martin Honert ist Erinnerung an den Werkprozeß gebunden. Er geht sogar soweit, daß jedes Werk eine völlig neue Erfahrung im Umgang mit Materialien beinhaltet. Diese jeweils neue Erfahrung zwingt ihn, gewissermaßen die Materialeigenschaften mit dem Bild der Erinnerung in Einklang zu bringen.

So wie ich dieses Werk zu Beginn geschildert habe, habe ich die Komplexität der Herstellung verschwiegen, also die über viele Etappen eruierten materialbedingten Möglichkeiten, die Realität der Fotografie in die Realität des räumlichen Ereignisses zu überführen. Wenn ich von "Bemalung" sprach, ist in Wirklichkeit "Malerei" angesagt, denn Martin Honert "malt" ein dreidimensionales Bild. Die Übertragung der Fotografie in die dritte Dimension enthält konstitutiv den malerischen Prozeß: Die Malerei als "Bemalung" erfolgt konzeptuell nicht nachträglich, sondern versteht sich als deren räumliche Ausweitung unter "skulpturalen" Bedingungen.

Die Anführungszeichen sind deshalb wichtig, weil sich Martin Honert nicht als Bildhauer betrachtet. Er schafft Bilder. Bilder der Erinnerung: das Gesehene als das in meiner Erinnerung Wahrgenommene oder als Fotografie Festgehaltene.

German text by Jean-Christophe Ammann / Translation by Ishbel Flett

(Extract - Full printed version available in the Museum)

MMK - Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main

About the work (english / deutsch) Kinderkreuzzug / Children’s Crusade

About the work (english / deutsch) Kinderkreuzzug / Children’s Crusade

In the mid-1980s, when Martin Honert began drafting his sculptural picture on the Children's Crusade, it was the heyday of the large picturesque gestures, so-called Neo-Expressionism, with established painters-cum-heroes like Gerhard Richter. In such a context, Martin Honert's intention of having the figures in his presentation sculpturally step forward out of the landscape plastic must have seemed naive or at the very least strange. It was to be his diploma project at the Düsseldorf Academy, where he had studied under Professor Fritz Schwegler. Once the work was complete, the initial response among his fellow students was not wholly without malice - it attracted great attention on the occasion of its first presentation along with the other diploma projects at the Academy, not least owing to its great size. With this work, Martin Honert had broken radically with everything which at that time was regarded as artistically worthy in terms of content and formally. Perhaps people at first thought it was an example of a historical painting.

The history to which the work refers dates back to the bellicose crusades advocated by the Church as so-called "Holy Wars" against "heathens and heretics" in the Middle Ages (1st-7th Crusade, 1096-1291). The legend would have it that the fervor of the crusades even seized hold of children in France and the Lower Rhine in their thousands and led to their ruin. The Children's Crusade from 1212 to 1214, that is after the 4th Crusade, ended chiefly when the children arrived in Marseilles and Genoa. Thousands of children were shipped by deceitful ship-owners not to the Holy Land, but to Alexandria and sold into slavery. The "pueri" mentioned by the historical sources were most probably servants, farm-hands and day laborers.

The Crusades linked the idea behind the pilgrimages (which at no other point in time captivated the masses to such an extent) with the fight against the heathens and the reconquest of the Holy Land from the end of the 11 th through to the end of the 13th century. They went hand in hand with various political, cultural, social and economic interests - with a devastating extent, for hundreds of thousands of persons lost their lives in the process.

The model on which Martin Honert's work is based could originatefrom a children's book or schoolbook, where, thanks to the child's imagination, the figures step out of the picture as if in a dream. However, in point of fact Honert drew on some picture in his memory, and not on an actual model. What he was interested in was reconstructing a memory and giving it a fixed form. In conversation with Heinz-Norbert Jocks, he described the history of the creation of the Children's Crusade as follows: "I started from a subjective history which has to do with the history classes I had in elementare school, where we talked about the crusades. Sometime, toward the end of a chapter, the teacher mentioned that there had also once been a children's crusade, but he would not go into detail. Instead, he emphasized that it had been far too awful and dreadful to discuss and further recommended that we immediately forget what he had said, as it was an all too embarrassing moment in history. Now of course he should not have said that, for it was that which really kindled my attention. I remember quite clearly how an image immediately came into my head. It was as though the blackboard swung open and a group of children in heavy clattering armor entered the classroom. In other words, the teacher's minor remark in passing called forth in me in a matter of seconds a picture, one that was just as full of life as was cinema." (Martin Honert in: Kunstforum International, October 1995, p. 282)

In Honert's work, painting, one could almost say the painting of the old masters, is completely in the thrall of the living, three-dimensional picture. You look at the painting as if gazing at a stage with a strong perspectival thrust. Your eyes are drawn via the life-sizefigures of 14 or 15-year-old children into the foreground of the landscape, as it were, until your eye gets lost somewhere in the background in the midst of the hilly landscape, following the nearly endless train of children. Perhaps we should describe the work as a "scenic model". There is an obvious comparison here to Martin Honert's contribution to the German pavilion at the 1995 Venice Biennial, which featured a group of figures from Erich Kästner's book "The flying classroom". In this respect, Honert said when interviewen by Boris Groys that: "I am fully aware that I am treading a tightrope here... But exactly this balancing act is what interests me." He went on: "Naturally, I am interested in the tightrope between reality and staged depiction or between reality and depictions of reality ... After all, the figures allude to toy figures which I have blown up to full life-size. And the intention is for the viewer to see clearly that they are figures that they are not depictions of persons, but the portrayal of figures." (Martin Honert in: Artforum, Feb. 1995) As if by some film trick, the figures seem to be stepping out of the past and into the present of the exhibition hall.

Martin Honert's conception was initially based only on completely three-dimensional figures and only later did he design the carefully constructed panoramic landscape. The figures are copies of toy knights, quoting the industrial mass production of plastic toys. Painted by hand, the figures imitate the industrial product. Honert therefore did not paint any further detail onto the individual facial characteristics of the figures, such as their pupils. And the typical way plastic toys stand, namely on little green platforms, is also emulated. Choosing plastic as a material, in this case molded polyester, constituted an important artistic decision when it came to elaborating such a work. Honert also did not smooth over the seams left by the mold. The material itself is an expressive medium and tends to give the figures a cheap, worthless appearance, avoiding any claim that they are art.

The idea of the knightly orders, who linked an ascetic with a chivalrous ideal (the monk's vows: poverty, chastity, obedience; the knight's mission: protect the oppressed) has forever inspired numerous childlike fantasies. The uniform of the knightly orders, such as the white tunic with the red cross, play an important role in the child's identification with his hero. Who does not remember the Crusader's oath, the castles and the adventures of Prince Ironheart, Richard Coeur de Lion and Ivanhoe. Inwardly, the child identifies completely with his role model, does not play knights or Indians, but is a knight or an Indian thanks to a costume or by staging the encounters with its toyfigures. In the case of the "Children's Crusade" the game suddenly becomes deadly senous.

Memory is the theme of most of Martin Honert's works and he often presents it by means of imagined images from childhood. The pictures are, as it were, frozen in time. Each Honert work originates in subjective experience and a subjective image, which has been transposed into his adult world. It is a children's dream from the viewpoint of an adult. However, there is nothing sentimental or nostalgic about it - on the contrary: The work instead has something depictive, indeed vivid, about it, like an illustration in an encyclopedia. In such works, the viewer will never confuse the imaginary with the actual event. Martin Honert's work is thus no illustration of a myth. Indeed, he explicitly avoids the "picture" becoming illusionist. Precisely the ruptures in the transition from two to three dimensions make this evident. Perhaps what first comes to mind are the somewhat naive displays using 3-D pictures in natural history and ethnographic museums or in a waxwork museum.

Martin Honert generally refers to everyday objects, as, in this case, to toys. "By means of the characteristics they share with toys, the figures are intended to show that the picture is a reconstruction. The distance thus created by means of the trivial helps to make the overall work more factual. " (Martin Honert in: Kunstforum International, October 1995, p. 288)

Immediately after first going on show in 1989 in the Johnen und Schöttle Gallery in Cologne, the monumental, large-size work became part of a private collection in New York and first went on show again as part of the exhibition "Views from Abroad" in the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York (Oct. 18, 1996 - Jan. 5, 1997). The MMK's collection contains numerous works by Martin Honert and we count ourselves lucky that, following the New York exhibition, precisely this key work by Honert has generously been loaned to us to be displayed in Frankfurt. Ten years after being made, it is the first time that it is being made accessible to a wider European audience.

Kinderkreuzzug

Mitte der Achtziger Jahre, als Martin Honert mit dem Entwurf für sein plastisches Bild zum Kinderkreuzzug begann, war die Zeit der großen malerischen Gesten, der sogenannten "Wilden Malerei" und etablierter Malerheroen wie Gerhard Richter. Martin Honerts Vorhaben, die Figuren seiner Darstellung aus dem Landschaftsbild plastisch heraustreten zu lassen, mußte damals naiv oder zumindest kurios anmuten. Es sollte seine Abschlußarbeit an der Düsseldorfer Akademie sein, wo er bei Prof. Fritz Schwegler studiert hatte. Nicht ganz ohne Häme war dann auch zunächst die Reaktion seiner Mitstudenten nach der Fertigstellung dieses Werkes, das alleine schon durch seine immensen Ausmaße große Aufmerksamkeit erhielt, anläßlich der ersten Präsentation auf dem Akademie-Rundgang. Martin Honert hatte mit dieser Arbeit einen radikalen Bruch vollzogen, mit allem was man damals inhaltlich und formal für bildwürdig erachtete. Man hielt das Werk vielleicht zunächst für Historienmalerei.

Die Geschichte, auf die sich das Werk bezieht, geht zurück auf die von der Kirche geförderten kriegerischen Kreuzzüge, die sogenannten "Heiligen Kriege" gegen "Ungläubige und Ketzer im Mittelalter" (1.-7. Kreuzzug von 1096-129 1). Der Kreuzzug-Eifer soll der Legende nach sogar Kinder in Frankreich und am Niederrhein zu Tausenden ergriffen und ins Verderben geführt haben. Der Kinderkreuzzug von 1212 bis 1214, zeitlich nach dem 4. Kreuzzug gelegen, endete größtenteils bereits in Marseille und Genua. Tausende von Kindern wurden von betrügerischen Reedern nicht ins Heilige Land sondern nach Alexandrien verschafft und als Sklaven verkauft. Die "pueri" der historischen Quellen waren wahrscheinlich Knechte, Landarbeiter und Tagelöhner.

Die Kreuzzüge verbanden das Gedankengut der Pilger- und Wallfahrten, die zu keinem anderen Zeitpunkt die Massen derart begeisterten, mit dem Kampf gegen die Heiden und der Rückeroberung des Heiligen Landes vom Ende des 11. bis zum Ende des 13. Jahrhunderts. Damit verbunden waren vielfältige politische, kulturelle, soziale und wirtschaftliche Interessen, allerdings mit verheerenden Ausmaßen, denn Hunderttausende von Menschen kamen dabei ums Leben.

Die Vorlage Martin Honerts zu diesem Werk könnte aus einem Jugend- oder Schulbuch stammen, bei der mit der Vorstellungskraft des Kindes die Figuren wie in einem Traum aus dem Bild heraustreten. Es handelt sich dabei allerdings um ein erinnertes Bild ohne Vorlage. Wichtig ist für Martin Honert die Rekonstruktion einer Erinnerung und deren Fixierung. Gegenüber Heinz-Norbert Jocks beschreibt er die Entstehungsgeschichte des Kinderkreuzzuges wie folgt: "Von einer subjektiven Geschichte gehe ich da aus, die mit meinem Geschichtsunterricht an der Volksschule zu tun hat, als die Kreuzzüge besprochen wurden. Irgendwann, am Ende eines Kapitels, erwähnte der Lehrer, daß es auch einmal einen Kinderkreuzzug gegeben hat, worüber er sich dann ausschwieg. Das sei zu schrecklich und entsetzlich, um sich damit näher auseinanderzusetzen, betonte er und riet, das, was er gerade angedeutet habe, da zu peinlich, gleich wieder zu vergessen. Das hätte er natürlich nicht sagen dürfen, denn dadurch hat er erst meine Aufmerksamkeit geweckt. Blitzartig, daran erinnere ich mich noch sehr genau, fiel mir dazu ein Bild ein. Es schien mir, als klappe die Wandtafel auf, damit eine Kindergruppe in schwerer klirrender Ritterausrüstung das Klassenzimmer betreten konnte. Also, die kleine Bemerkung des Lehrers am Rande des Unterrichts hatte in mir in Sekundenschnelle ein Bild hervorgerufen, und zwar so plastisch wie im Kino." (Martin Honert in: Kunstforum International, Oktober 1995, S. 282)

Die Malerei, fast ist man geneigt sie als altmeisterlich zu bezeichnen, steht ganz im Dienste des plastischen Bildes. Man blickt wie in ein Bühnenprospekt mit stark perspektivischer Wirkung. Der Betrachter wird über die lebensgroßen Figuren, von etwa 14- 15jährigen Kindern, im Vordergrund quasi in das Landschaftsbild hineingeführt, bis man sich, dem schier endlosen Zug von Kindern folgend, im Hintergrund in der Weite der hügeligen Landschaft verliert. Man könnte das Werk auch als "szenisches Modell" beschreiben. Der Vergleich mit der Figurengruppe zu Kästners "Das fliegende Klassenzimmer", Martin Honerts Beitrag für den Deutschen Pavillon in Venedig 1995, liegt nahe. Diesbezüglich äußerte sich der Künstler in einem Interview gegenüber Boris Groys wie folgt: "Ich bin mir über diese Gratwanderung sehr im klaren ... Aber genau das interessiert mich auch, dieser Balanceakt." Und weiter: "Natürlich interessiert mich die Gratwanderung zwischen Realität und Inszenierung oder zwischen Realität und Darstellung der Realität ... Die Figuren zitieren ja Spielzeugfiguren, die habe ich dann 1:1 lebensgroß gemacht. Man sollte aber richtig sehen, daß es Figuren sind - daß es nicht Darstellungen von Menschen sind, sondern es sind Darstellungen von Figuren." (Martin Honert in: Artforum, Febr. 1995) Wie in einem Filmtrick scheinen die Figuren wie aus einer anderen Zeit in unsere Gegenwart des Ausstellungsraumes herauszutreten.

Martin Honerts Konzeption ging zunächst von den vollplastischen Figuren aus und erst als zweites entwarf er das durch und durch konstruierte Landschaftspanorama. Die Figuren zitieren Spielzeugritter und die industrielle Massenherstellung von Plastikspielzeug. Die von Hand bemalten Figuren imitieren das industrielle Produkt, daher wurde auf ein weiteres Ausmalen der individuellen Gesichtszüge wie der Pupillen verzichtet. Und das für Plastikspielzeug typische Stehen der Figuren auf grünen Plinthen wurde mitübernommen. Der Kunststoff als Material, in diesem Fall ein Polyesterguß, ist eine wichtige künstlerische Entscheidung für die Ausarbeitung eines solchen Werkes. Die Gußnähte wurden daher auch nicht geglättet. Das Material wird zum Ausdrucksträger und gibt den Figuren einen eher billigen wertlosen Anschein, der jeglichen Kunstanspruch vermeidet.

Die Vorstellung der Ritterorden, die das asketische mit dem ritterlichen Ideal verbindet (Gelübde des Mönchs: Armut, Keuschheit, Gehorsam; Aufgabe des Ritters: Schutz der Bedrängten) beflügelte seit jeher zahlreiche kindliche Phantasien. Die Ordenstracht, wie der weiße Waffenrock mit rotem Kreuz, spielt bei der Identifikation des Kindes mit seinem Helden eine wichtige Rolle. Wer erinnert sich nicht an Kreuzfahrer-Eid, Ritterburgen und die Abenteuer von Prinz Eisenherz, Richard Löwenherz und Ritter Ivanhoe. Das Kind identifiziert sich innerlich vollständig mit seinem Vorbild, es spielt nicht Ritter oder Indianer, es ist ein Ritter oder ein Indianer durch Kostüm und Inszenierung oder mittels Spielzeugfiguren. Im Fall des "Kinderkreuzzuges" schlägt das Spiel allerdings in tödlichen Ernst um. Thema der meisten Arbeiten Martin Honerts ist die Erinnerung, die er mit imaginierten Bildern der Kindheit hervorruft. Es handelt sich um stillgelegte Bilder. Jede Arbeit des Künstlers hat ihren Ursprung in subjektivem Erleben und einem subjektiven Bild, das in sein Erwachsensein hinübergewechselt ist. Es ist ein Kindertraum aus der Sicht des Erwachsenen. Es hat jedoch nichts Sentimentales oder Nostalgisches, ganz im Gegenteil. Das Werk hat vielmehr etwas Abbildhaftes ja Anschauliches wie man es in Lexikon-Illustrationen findet. Der Betrachter wird jedoch das Imaginative mit dem Realen niemals verwechseln. Martin Honerts Werk ist keine Illustration eines Mythos. Auch vermeidet der Künstler, daß das "Bild" zu illusionistisch gerät. Gerade die Brüche des Übergangs vom Zwei- ins Dreidimensionale machen dies erkennbar. Man denkt vielleicht sogar an die etwas naive Darstellung von plastischen Bildern in Natur- und Völkerkundemuseen oder im Panoptikum. Martin Honert bezieht sich meist auf den Alltagsgegenstand, wie in diesem Fall das Spielzeug: "Mittels des Spielzeugcharakters soll der Rekonstruktionscharakter eines Bildes sichtbar werden. Diese Distanz per Gebrauch des Trivialen hilft, etwas zu versachlichen." (Martin Honert in: Kunsforum International, Oktober 1995, S.288)

Das monumentale, raumfüllende Werk war bereits 1989 direkt nach seiner ersten Ausstellung in der Galerie von Johnen und Schöttle in Köln in eine New Yorker Privatsammlung gelangt, und es wurde zunächst anläßlich der Ausstellung "Views from Abroad" im Whitney Museum of American Art in New York (18.10.1996 - 5.1.1997) gezeigt. Martin Honert ist mit zahlreichen Werken in der Sammlung des Frankfurter Museums für Moderne Kunst vertreten und man muß es als Glücksfall bezeichnen, daß gerade dieses Schlüsselwerk des Künstlers durch eine großzügige Leihgabe, im Anschluß an die New Yorker Präsentation, in unserem Haus gezeigt werden kann. Es wird damit erstmals, zehn Jahre nach seiner Entstehung, einer größeren, europäischen Öffentlichkeit zugänglich gemacht.

German text by Mario Kramer / Translation by Jeremy Gaines

(Extract - Full printed version available in the Museum)

MMK - Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main

Bibliography

Bibliography

Ammann, Jean-Christophe: Martin Honert. Verlag Wilk, Friedrichsdorf, 1994.

ISBN: 3-88270-472-1

offers / Requests offers / Requests  |

About this service |

|---|

Exhibition Announcements Exhibition Announcements  |

About this service |

|---|

Visualization |

Learn more about this service | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Interested in discovering more of this artist's networks?

3 easy steps: Register, buy a package for a visualization, select the artist.

See examples how visualization looks like for an artist, a curator, or an exhibition place: Gallery, museum, non-profit place, or collector.

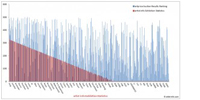

Exhibition History

|

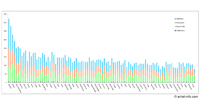

SUMMARY based on artist-info records. More details and Visualizing Art Networks on demand. Venue types: Gallery / Museum / Non-Profit / Collector |

||||||||||||

| Exhibitions in artist-info | 44 (S 7/ G 37) |

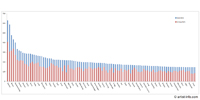

Did show together with - Top 5 of 625 artists (no. of shows) - all shows - Top 100

|

||||||||||

| Exhibitions by type | 44: 8 / 19 / 16 / 1 | |||||||||||

| Venues by type | 33: 7 / 11 / 14 / 1 | |||||||||||

| Curators | 17 | |||||||||||

| artist-info records | Feb 1991 - Sep 2016 | |||||||||||

|

Countries - Top 5 of 7 Germany (30) United States (3) France (3) Italy (2) Spain (1) |

Cities - Top 5 of 24 Frankfurt am Main (11) New York (3) Bremen (3) Bonn (3) Düsseldorf (3) |

Venues (no. of shows )

Top 5 of 33

|

||||||||||

Curators (no. of shows)

Top 5 of 17

|

| Kunstmuseum Bonn | G | Jun 2016 - Sep 2016 | Bonn | (181) | +1 | |

| Berg, Stephan (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Adolphs, Volker (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Kasseler Kunstverein | G | Jul 2015 - Aug 2015 | Kassel | (123) | +0 | |

| Schmidt, Sabine Maria (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Carré d’art - Musée d’art Contemporain | G | May 2015 - Sep 2015 | Nîmes | (118) | +0 | |

| Chevrier, Jean-François (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Pijollet, Élia (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Deutsche Bank Collection - Artists | S | Apr 2015 - Apr 2015 | Frankfurt am Main | (1) | +0 | |

| Kunsthalle Bremen | G | Jun 2013 - Jan 2014 | Bremen | (197) | +0 | |

| Schmidt, Sabine Maria (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen | G | Feb 2013 - Jul 2013 | Düsseldorf | (55) | +0 | |

| Cragg, Tony (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Gohr, Siegfried (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Fleck, Robert (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Ackermann, Marion (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Müller-Schareck, Maria (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Keep reading |