Artist | Andreas Slominski (*1959)

https://www.artist-info.com/artist/Andreas-Slominski

Biography

Biography

born in 1959

About the work (english / deutsch)

About the work (english / deutsch)

Traps

Since 1984 Slominski has been concerning himself with something perhaps best described as field studies - the aesthetic exploration of the most casual forms of everyday perception. The inconspicuousness of the objects and materials selected often has a treacherous and also cunning side to it, making us chuckle. In Slominski’s works, the normal function of the objects is somehow always subverted, the context and contents altered. In so doing, everything is kept in a decidedly unsteady balance. The incidental becomes a sculpture, and the claim originality is undermined by that lack of stable balance. The works are often ambiguous, a characteristic that frequently ambushes the observer.

Beauty and horror, banality und sublimeness, wit and profound seriousness coalesce, the admixture that emerges forming a complex artwork.

Slominski’s systematic collection of commonly available animal traps could be regarded as the basis of this way of visual thinking. Traps set to catch the unwary, viewed as independent three dimensional sculptures and placed as exhibits in galleries or museums, often take the notion of exhibiting to the limits. It is the reality of the traps as objects in their own right that first generates the artwork.

All of Slominskis works can be „traps“ in a metaphorical sense. To his mind, the notion of a „trap“ functions as a meta-concept. lt became a solution in his search for his particular artistic form of expression, for an artistic strategy. Slominski constructs „trap“ forms using everyday objects and by combining the different uses to which they can be put.

He frequently adopts as a structural principle harmonious proportional relations, such as the „golden section“, known in the applied arts and architecture since the days of Ancient Grecce. All endeavours to use this compositional principles were informed by the notion that it enabled the „true“ proportions of the human body to be grasped and rendered in canonical form.

In his Untitled of 1987, common unused washing-up and dusting clothes as well as tea towels are placed on a traditional plinth. They are folded and stacked with exceptional care, indeed almost with an obsessive mania. The intentional ordering of the clothes strikes the eye even at first glance. This is a process which is calculated down the smallest detail and thus apparently precludes chance, although this does not rob the structure of its incredible tenderness and poetry.

Yet this is also the order in our clothes cupboard at home. Cleanliness and purity are not just the supreme order of the day in Gennany. They can also be our undoing. One thinks involuntarily of the functions of the different textiles, their absorptive capacity or their dusting qualities, their fluffy softness or their impregnated smoothness. They are useless and useful at one and the same time. This is poetry of the banal, yet serious poetry. Protected from any particles of dust in a bacteria-free zone, the cleaning cloths lie like snow-white in her glass coffin in a display case. But who kisses dusters?

Where can a distinction be made between image, copied image and the copied things itself, i.e. between signifier and signified? There is an extremely fine line between objectiveness and abstraction.

There can, as with all Slominskis works, infact be no real talk of objet trouvés here. After a long search, the objects and materials selected are then sifted further according to numerous different criteria.

The „Children’s Bicycle“ is probably the piece that most provokes the majority of the museum visitors who are not prepared for it. If we were to encounter it Ieaning against a wall somewhere in the city centre it would certainly surprise us. In such a context it would have an inviolable aura about it, and no one would dream of stealing something off it or even making off with the cycle itself. But how did it end up in the museum? Does the completely overladen bicycle bear all the belongings of a homeless child? The bags, which seem to be packed onto it without any discernible order, are in fact distributed economically in terms of mass and weight. The plastic bags are, for the main, from department stores or supermarkets. Yet everyone of us knows: nothing was bought there. The household contents here have been hunted together, collected and stored. The shape the „children’s“ bike has seems to contradict its current function. Yet it is no objet trouvé. After seeing the „original“ larger-frame adult’s bike here in Frankfurt, and finding it, as if glancing in a mirror, to bear a sort of elective affinity to his work, Slominski photographed it and then set about carefully constructing it. His activity in this regard has an almost ineluctable consequence: it is a children’s bike, packed and laden as if for survival in an emergency by someone without a home. By being switched from the adult world into the world of children it has been transposed into an almost abstract picture. The work has become an inexorable, existential question for the artist himself. It is an artwork about existence, including that of the observer. In 1988, when asked in an interview what it was he sought in art, Slominski answered: „Life“.

German text by Mario Kramer / Translation by Jeremy Gaines

(Extract - Full printed version available in the Museum)

MMK - Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main

Fallen

Das, womit sich Andreas Slominski seit 1984 beschäftigt, könnte man ganz allgemein als Feldforschung beschreiben - ein ästhetisches Erkunden von Alltagswahrnehmungen beiläufigster Art. In der Unscheinbarkeit der ausgewählten Dinge und Materialien liegt oft etwas Heimtückisches, aber auch Listiges, was uns schmunzeln läßt. Es kommt immer zu einer Umwendung der Funktion, des Kontextes und der Inhalte. Dabei hält Andreas Slominski alles in einem überaus labilen Gleichgewicht. Das Beiläufige wird zur Skulptur. Die Originalitätsansprüche werden durch Instabilität ins Wanken gebracht. Die Werke haben oft einen doppelten Boden und bilden einen Hinterhalt.

Schönheit und Entsetzen, Banalität und Erhabenheit, Witz und tiefer Ernst vermischen und durchdringen sich zu einem komplexen Werk.

Als Basis seines bildnerischen Denkens könnte man seine systematische Sammlung von handelsüblichen Tierfallen bezeichnen. Die fängisch gestellte Falle, als eigenständige plastische Skulptur betrachtet und als Exponat in Galerie- und Museumsräume versetzt, grenzt oftmals an die Ausstellbarkeit. Die eigenständige Wirklichkeit der Falle als Objekt erzeugt erst das Kunstwerk.

Alle Arbeiten Slominskis können „Fallen“ im übertragenen Sinne sein. Die Vorstellung der „Falle“ ist für ihn zu einem Überbegriff geworden. Sie wurde zur Lösung auf der Suche nach seiner eigenen künstlerischen Ausdrucksform, zur künstlerischen Strategie.

Aus alltäglichen Gebrauchsgegenständen und mit der Kombination ihrer unterschiedlichen Gebrauchswerte, konstruiert Andreas Slominski „Fallen“-Formen.

Als Ordnungsprinzip benutzt er häufig harmonische Proportionsverhältnisse, z.B. den „Goldenen Schnitt“, deren Anwendung wir in der bildenden Kunst und Architektur seit der Antike kennen. Alle Bemühungen um diese Gliederungs- und Kompositionsprinzipien wurden immer von der Idee getragen, die „wahre“ Proportion der menschlichen Gestalt zu fassen und zu kanonisieren.

Im Werk Ohne Titel von 1987 werden gewöhnliche, unbenutzte Spül-, Wisch- und Staubtücher auf den traditionellen Sockel gehoben. Mit äußerster Sorgfalt, fast mit obsessiver Manie sind sie gefaltet und gestapelt. Die absichtsvolle Anordnung wird auf den ersten Blick deutlich. Ein bis ins kleinste Detail kalkulierter Prozeß, der den Zufall völlig auszuschließen scheint; was dem Gebilde jedoch nichts von seiner ungeheuren Zartheit und poetischen Erscheinung nimmt.

Es ist aber auch die Ordnung in unserem häuslichen Wäscheschrank. Sauberkeit und Reinheit sind nicht nur in Deutschland oberstes Gebot. Sie können auch zum Verhängnis werden. Man denkt unwillkürlich an die Funktion der unterschiedlichen Gewebe, ihre Saugfähigkeit oder ihre Wischqualität, ihre flauschige Weichheit oder imprägnierte Glätte. Sie sind wertlos und wertvoll zugleich. Es ist eine Poesie des Banalen. Ein ernstes Spiel. Vom Staub keimfrei geschätzt, liegen die Reinigungstücher in einer Vitrine wie Schneewittchen in ihrem gläsernen Sarg. Aber wer küßt schon Staubtücher?

Wo ist der Unterschied zwischen Bild, Abbild und Abgebildetem, zwischen Bedeutung und Bedeutendem? Es herrscht eine sehr feine Balance zwischen Gegenständlichkeit und Abstraktion.

Von „Fundstücken“ kann, wie bei allen Arbeiten Slominskis, hier eigentlich keine Rede mehr sein. Nach langer Suche müssen die Gegenstände und Materialien bei der Auswahl zunächst vielfältigen Qualitätskriterien genügen.

Das „Kinder-Fahrrad“ ist wahrscheinlich für die meisten unvorbereiteten Museumsbesucher die weitreichendste Provokation. Würde es doch, wenn es uns an einer Straßenecke an der Konstabler Wache begegnete, große Verwunderung hervorrufen. Es hätte dort eine unantastbare Aura, niemand käme auf die Idee, etwas wegzunehmen oder gar dieses Fahrrad zu stehlen. Wie aber kommt es ins Museum? Trägt das übervoll bepackte Rad das ganze Hab und Gut eines obdachlosen Kindes? Das vollständig ungeordnet erscheinende Gepäck folgt durchaus einer ökonomischen Verteilung von Masse und Gewicht. Die Plastiktüten stammen zumeist aus Kaufhäusern oder Supermärkten. Man weiß aber genau: hier wurde nichts eingekauft. Der Hausstand ist vielmehr zusammengesucht, gesammelt und gehortet. Die Art des „Kinder“-Rades scheint seiner heutigen Funktion zu widersprechen. Es ist jedoch kein Fundstück. Nachdem Andreas Slominski das „originale“ große Fahrrad eines Erwachsenen hier in Frankfurt sah und in ihm, wie in einem Spiegelbild, eine Art Wahlverwandtschaft fand, hat er es fotografiert und bis ins kleinste Detail konstruiert. Sein Tun hat dabei eine geradezu unausweichliche Konsequenz. Es ist jedoch ein Kinderfahrrad, bepackt und bestückt wie für das Überleben in einer Notsituation ohne Zuhause. Es wurde durch die Wendung von der Erwachsenen zur Kinderwelt in ein nahezu abstraktes Bild übertragen. Das Werk wurde zu einer unerbittlichen, existentiellen Frage für den Künstler selbst. Es ist ein Werk über die Existenz, auch die des Betrachters. 1988 antwortete Andreas Slominski in einem Interview auf die Frage, was er in der Kunst suche: „Das Leben“.

Text von Mario Kramer

(Auszug - Der vollständige Text ist als Informationsblatt beim Museum erhältlich)

MMK - Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main

Bibliography

Bibliography

Ammann, Jean-Christophe/Kramer, Mario: Andreas Slominski. Verlag Wilk, Friedrichsdorf, 1993.

ISBN: 3-9803053-1-7

offers / Requests offers / Requests  |

About this service |

|---|

Exhibition Announcements

Exhibition Announcements

Visualization |

Learn more about this service | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Interested in discovering more of this artist's networks?

3 easy steps: Register, buy a package for a visualization, select the artist.

See examples how visualization looks like for an artist, a curator, or an exhibition place: Gallery, museum, non-profit place, or collector.

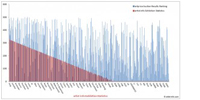

Exhibition History

|

SUMMARY based on artist-info records. More details and Visualizing Art Networks on demand. Venue types: Gallery / Museum / Non-Profit / Collector |

||||||||||||

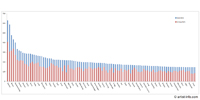

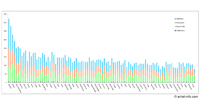

| Exhibitions in artist-info | 115 (S 28/ G 87) |

Did show together with - Top 5 of 1531 artists (no. of shows) - all shows - Top 100

|

||||||||||

| Exhibitions by type | 115: 31 / 34 / 47 / 3 | |||||||||||

| Venues by type | 80: 20 / 20 / 37 / 3 | |||||||||||

| Curators | 51 | |||||||||||

| artist-info records | Jun 1988 - Nov 2024 | |||||||||||

|

Countries - Top 5 of 13 Germany (84) France (5) United States (5) Belgium (3) Italy (2) |

Cities - Top 5 of 44 Frankfurt am Main (19) Berlin (17) Hamburg (11) Köln (8) Paris (4) |

Venues (no. of shows )

Top 5 of 80

|

||||||||||

Curators (no. of shows)

Top 5 of 51

|

| Kunst Museum Winterthur | G | Sep 2024 - Nov 2024 | Winterthur | (166) | +1 | |

| Kost, Lynn (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Tower - MMK | G | Feb 2017 - May 2017 | Frankfurt am Main | (10) | +0 | |

| Kramer, Mario (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Weserburg | Museum für moderne Kunst | G | May 2016 - Feb 2017 | Bremen | (121) | +0 | |

| Deichtorhallen Hamburg - Halle für aktuelle Kunst | S | May 2016 - Aug 2016 | Hamburg | (59) | +0 | |

| Luckow, Dirk (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Galerie Bärbel Grässlin | S | Apr 2016 - May 2016 | Frankfurt am Main | (210) | +0 | |

| Galerie Anita Beckers | G | Sep 2015 - Oct 2015 | Frankfurt am Main | (184) | +0 | |

| Keep reading |