New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic, 1919–1933

October 4, 2015–January 18, 2016, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

Curator: Stephanie Barron, Nana Bahlmann

Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity, was an approach to art-making that emerged in Germany in the aftermath of World War I, simultaneous with the formation of the nation’s firstdemocracy, the Weimar Republic. Less a style or a cohesive movement than a shared attitude, New Objectivity rejected the tendencies toward exoticism and impassioned subjectivity that had characterized Expressionism, the predominant prewar avant-garde.

In contrast, artists who became associated with New Objectivity—a term popularized in 1925 by German art historian Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub—observed the modern environment with divergent styles that were sober, unsentimental, and graphic. This exhibition examines the varied ways these artists depicted and mediated contemporary reality; by presenting photography alongside painting and drawing, it offers the rare opportunity to examine and compare New Objectivity across its different media.

While they were not unified by manifesto, political tendency, or geography, these artists did share a skepticism regarding German society in the years following World War I and an awareness of the human isolation brought about by social change. They chose themes from contemporary life, using realism to negotiate rapidly changing social and political conditions. By closely scrutinizing everyday objects, modern machinery, and new technologies, these artists rendered them unnatural—as uneasy as individuals alienated from each other and their surroundings. As if to correct the chaos of wartime, they became productive voyeurs, dissecting their subjects with laser focus, even when overemphasis on detail came at the expense of the composition as a whole.

New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic, 1919–1933 is divided into five thematic sections that address the competing and at times conflicting approaches that the adherents to this new realism applied to the tumultuous and rapidly changing Weimar years. Some of the works included here attack political and social wrongs; others seem nostalgic or long for the past; still others focus on objects and human subjects, rendered in uninflected surfaces and seemingly frozen in time. The overall severity of New Objectivity reflects the harshness of its historical moment and the dedication of its artists to capture, if not to critique, the turmoil that surrounded them.

Adolf Hitler’s appointment as Germany’s chancellor in January 1933 brought New Objectivity to a premature end. The cultural ministry of Hitler’s Third Reich declared many artists and artworks “degenerate,” and a significant portion of New Objectivity’s output was lost or destroyed in the years between 1933 and 1945. While the view we have today of New Objectivity is thus necessarily a partial one, it neverthelessoffers a compelling snapshot of a nation, and its artistic avant-garde, between the two world wars.

Life in the Democracy and the Aftermath of War

The Weimar Republic, Germany’s first democracy, was a social, political, and economic experiment initiated in the immediate aftermath of World War I, which had devastated the nation. Lasting from 1919 until 1933, the Weimar era was characterized by uneasy contradictions: at the same time that people enjoyed newfound freedoms and liberties, their daily realities continued to be deeply troubled by the consequences of war and the ensuing political and economic instability.

Some of the most harrowing images of the war emerged in the 1920s. Even a decade after fighting in the trenches, artists were still processing their wartime experiences and struggling to give form, however gritty, to chaos and brutality witnessed first-hand. Those who directly confronted the lingering trauma of war in their work, including Otto Dix, Heinrich Davringhausen, August Sander, Rudolf Schlichter, and Jeanne Mammen, often represented street scenes populated with the collateral sufferers of the war—disabled veterans, unemployed workers, prostitutes, and murder victims. The amputee, a common sight throughout Weimar Germany, served as the emblem of a society irreparably scarred, both literally and metaphorically. Prostitution was widespread, as was sexual aggression and violence, which artists approached with a mixture of fascination and revulsion.

In addition to raw depictions of those suffering under the Weimar Republic, artists also took as their subjects those in power who benefited from the deprivation and chaos of the period. Several, including George Grosz, Georg Scholz, and Karl Hubbuch, cast a critical eye on the rampant black-market profiteering and political extremism that threatened a young democracy already crippled by hyperinflation. Employing satire and exaggeration, New Objectivity artists offered close observations that emphasized the ugly and the grotesque as an intentional affront to comfortable bourgeois society.

Bourgeois Leisure And Nightlife

Smoke-filled nightclubs, dance floors, and cafes, all brimming with flamboyantly dressed patrons, are among the most enduring images of Weimar Germany. Berlin in particular was a prime locus of activity in the era that became known as the Golden Twenties. For the bourgeoisie, endless revelry, whether in posh bars or seedy cabarets, was a means to escape from a reality that, by day, was complicated by the pervasive social and economic troubles of the urban metropolis.

Artists catalogued a wide spectrum of Weimar’s many social spaces, from the formal dancehall of Max Beckmann’s Dance in Baden-Baden to the garish fetish club of Rudolf Schlichter’s Tingel-Tangel. Under the harsh light of New Objectivity, what might have been deliriously pleasurable in reality has been stultified and made grotesque, as in Paul Kleinschmidt’s Drunken Society, which offers a sobering picture of the after- math of overindulgence.

Social Misery

Wartime food shortages and rising inflation reached a crisis by war’s end. The Treaty of Versailles, signed in 1919, demanded that Germany pay 132 billion gold marks in reparations, which crippled the economy. Hyperinflation took hold, peaking in November 1923, when a loaf of bread cost 200 billion marks. The following year, Germany and the United States signed the Dawes Plan, which provided economic relief. But stability was short-lived: the crash of the New York Stock Exchange in 1929 forced the U.S. to withdraw economic support to Germany, sending the country into a tailspin of record unemployment and pervasive poverty.

Images of wounded veterans, such as those in Otto Dix’s prints The Match Seller and Card Players, made visible the long-lasting effects of war. August Sander included the unemployed and the disabled in his photographic documentation of social types, while other artists such as Georg Scholz and Karl Hubbuch created portraits of the downtrodden that reflected the harsh realities of many.

Prostitution

The early Weimar era was marked by widespread fears and anxieties about moral decay. Female prostitutes, working in rising numbers in major cities during and after World War I, were seen as emblematic of this moral decline, especially because they were believed responsible for the spread of venereal disease. Prior to 1927, the year the German government decriminalized prostitution and launched a sexual health initiative, prostitution had been illegal, although it was tolerated in certain cities (including Berlin), where regulations were in place to police registered prostitutes, whose movements were strictly limited.

New Objectivity artists depicted prostitutes most commonly as debased commodities, calculated to arouse revulsion rather than to be arousing. Artists such as George Grosz and Otto Dix de-eroticized and dehumanized the sex workers they so often made the subjects of their work, while at the same time treating them as sexually voracious objects, thereby blurring the distinction between delight and disgust.

Lustmord

Several shocking cases of Lustmord, or sexual murder, rocked Weimar Germany in the early 1920s. Lustmord was defined as a murder committed in a sexual frenzy, in which the act of mutilating and defiling the body of the victim substituted for the sexual act. Such titillating crimes, further sensationalized by the news media, fueled existing obsessions with sexual deviance.

Quickly becoming a part of popular visual and literary culture (as demonstrated by the selection of books and magazines in this gallery), Lustmord also captivated the imagination of a number of New Objectivity artists. Otto Dix, whose works following World War I often explored violence and human brutality, depicted himself as a sex murderer for a 1920 self-portrait, and featured the gruesome aftermath of similar crimes in the etching on view here—an image as haunting as Rudolf Schlichter’s Sex Murder, rendered in sketchy watercolor and crayon. Heinrich Davringhausen’s The Sex Murderer foregoes explicit gore and invests an image of the reclining nude—a trope of classical painting— with psychological foreboding by picturing a predator lurking under the bed, lying in wait to attack his unsuspecting but seemingly sexually available victim.

Politics

1918 marked the end of World War I and the beginning of a period of unprecedented political turmoil in Germany. In response to mounting social and economic problems, the newly formed German Communist Party called for mass strikes, leading to the Spartacist uprising in Berlin that ended in the state-sponsored assassinations of Communist leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. Political tensions cooled after the official formation of the Weimar Republic and the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in the summer of 1919, fostering a short period of stability before the hyperinflation crisis of the early 1920s.

Although the artists associated with New Objectivity were not uniformly leftist, many of them used their work as a vehicle for liberal sociopolitical critique. George Grosz and Georg Scholz, both members of the November Group (a radical artists’ organization), specifically targeted corrupt politicians, conservative war veterans, monarchists, and profiteers, caricaturing their complicity in the misfortunes of the nation. They did so in the midst of a series of events that set the stage for Germany’s next calamitous chapter.

The National Socialist German Worker’s Party (more commonly known as the Nazi Party) was formed in 1920; three years later, party leader Adolf Hitler attempted an overthrow of the government that landed him in prison, where he wrote his manifesto, Mein Kampf (My Struggle), famously scapegoating Jews and Communists for the nation’s troubles. Former field marshal Paul von Hindenburg’s election to the presidency in 1925 put into motion Hitler’s appointment to the chancellery in 1933; when Hindenburg died in 1934, Hitler installed a dictatorship, ending the Weimar Republic and initiating the Third Reich.

The City and the Nature of Landscape

The Weimar Republic gave rise to the urban metropolis in Germany—a space of new possibilities emerging from modernization and political and sexual freedom, but also one that denoted a growing alienation from nature and between individuals. In painting and photography, artists thematized the frictions between the rural and the urban—the former seen as connected to the past, the latter seemingly imbued with the future. Artists such as Georg Schrimpf and Georg Scholz sought to contrast the rapid encroachment of twentieth-century industrialization with nostalgia for the supposedly simpler, bucolic life of the nineteenth century. A sense of displacement characterizes how these artists related to landscape, suggesting an erosion of the boundaries between natural and manmade environments.

A number of photographers created striking images of the Neues Bauen (New Building) architectural style. Arthur Köster and Werner Mantz, for example, offered close views of modern materials (poured and reinforced concrete, steel, and plate glass) framed with tight cropping, experimental lighting, and overlapping forms. These postwar housing developments were intended to integrate light and air into modern, costeffective, “healthful dwellings.” Most often these highly ordered photographs show no sign of inhabitants, and a mood of stillness dominates.

Painters also reflected this mood of urban alienation. With his restrained colors, smooth paint application, and cool objectivity, Anton Räderscheidt cultivated a sense of eerie tranquility that manages to be simultaneously hyper-real and unreal. Although the idealized, rural landscapes favored by artists such as Schrimpf generally lacked overt ideological and social content, they can be seen as a retreat from the challenges posed by the city environment.

Schrimpf and Classicism

Georg Schrimpf was one of the major progenitors of what was termed the classicist wing of New Objectivity, which was centered in Munich. He looked to contemporaneous Italian painter Carlo Carrà in developing a style that looked back to Renaissance precedents. In the years just before World War I, Carrà, in conjunction with Giorgio de Chirico, had developed a style called Pittura metafisica (metaphysical art), which employed single-point perspective to create illusionistic spaces populated by enigmatic objects, all to disquieting effect. The polemical magazine Valori plastici spread their influence across Europe, offering a counterpoint to the anti-establishment avant-garde.

For Schrimpf, adopting a classicist style was part of a search for calmness, harmony, and timelessness in the midst of the turbulence of the Weimar Republic. By contrast, some of Schrimpf’s contemporaries, especially Heinrich Davringhausen and Carlo Mense, appropriated classicist tropes to heighten the eerie sense of psychological disturbance imbued in their work.

Man and Machine

The Weimar era, which alternated between times of great want and incredible wealth, engendered varying attitudes toward the objects of everyday life. Modernization and technological innovation made mass production possible, while urbanization and a robust advertising industry created mass markets ready to shop.

New Objectivity practitioners developed a range of iconographies and allegories through contemplative studies of disparate, everyday objects. Artists focused on banal items of daily life (a dish towel, a broom, a bucket, an egg cup), newly mechanized appliances (an electric coffee pot, a sewing machine), or botanical species or organic forms (agave plants, rubber trees, eggs). As painter Grethe Jürgens observed: “One paints pots and rubbish piles, and then suddenly sees these things quite differently, as if one had never before seen a pot . . . . One looks at technological objects with different eyes when one paints them or sees them in new paintings.”

Closeup photographs by Hans Finsler, Albert Renger-Patzsch, and Aenne Biermann divested objects of their contextual identity, appearing as studies in texture and composition—an approach that worked particularly well for companies that wanted to promote their products in advertisements and brochures. Finsler and Renger-Patzsch emphasized mass production through serial groups of objects. These “object portraits” not only register the mundane details of daily existence but also reflect the ways in which new commodities, and consumerism in general, had begun to insinuate themselves into modern German life.

Still Life and Commodities

The rapid modernization of industry in the Weimar era expanded mass production, accelerated urbanization, and created new relationships between people and technology. The factory floor symbolized both the displacement of man and his historical advancement. Artists expressed the mix of fascination and skepticism with which Germans (and their fellow Europeans) viewed the technological progress of the period. New Objectivity paintings of industry oscillate between recognizing the transformative power of new technologies and conveying the lack of humanity embedded in contemporary industrial practices.

Photographers such as Hans Finsler and Albert Renger-Patzsch and painters such as Carl Grossberg rendered machines with formal beauty and rigorous clarity—positioned like works of art set on plinths on a factory floor. Time seems frozen in these images; the actual human labor associated with the machines is often invisible and the anonymity of the machinery prevails. Renger-Patzsch believed photography was uniquely capable of capturing “modern technology’s rigid linear structure,” while Grossberg rendered the technological components of machines with photographic precision, registering every detail with equal exactitude. This feat— impossible to attain in a photograph—challenged the supposed inability of painting to offer an objectively credible (re) presentation of the object itself.

Exotic Plants

The exoticism of cacti and succulents—species not native to Germany—explains their prevalence in the still lifes on view as well as their widespread popularity as houseplants during this period. With their dense green stems, leaves, and prickly protrusions, exotic plants lack the sentimental beauty of flowers, offering instead indelicate, monolithic forms that evoke what was referred to in the Weimar era as “thing character.” Many New Objectivity painters and photographers, including Aenne Biermann, Fritz Burmann, Xaver Fuhr, and Georg Scholz, favored exotic plants because they lent themselves to representations of nature as inanimate object; such an approach assimilated nature to the hard aesthetic of commodities and machines that dominated the reality— and the imaginary—of the era.

New Identities: Type and Portraiture

The works in this section are perhaps those most commonly identified with New Objectivity: unflinching portrayals of the men, women, and children of Weimar Germany. Many of these portraits simultaneously typify the subject as part of a group while allowing him or her to remain outside of it, offering a snapshot of the tensions between collectivity and individuality that characterized the era.

In unsentimental works that defied traditional portraiture, artists frequently took as their subjects the social types of Weimar Germany, reflecting a more generalized approach to classification that extended to the systematic categorization of handwriting, facial characteristics, and sexual traits in an attempt to stabilize and organize societal structure. August Sander’s monumental photographic project documenting the people of the twentieth century reflects the widespread desire for social order in a time of constant change and upheaval.

While New Objectivity artists shared a general outlook, their approaches to portraiture remained diverse. Otto Dix’s portraits, for example, are often exaggerated, revealing the seemingly disturbing or strange qualities of his subjects, while Christian Schad’s portraits are more sober and straightforward. Portraiture of the period also reflects how traditional notions of gender and sexuality were being challenged in Germany. Painters and photographers frequently took as their subject the newly emancipated German woman, dubbed the “New Woman,” a fashionable figure often associated with lesbianism and androgyny who sported bobbed hair and often wore traditionally masculine attire, including suits and monocles. While some of these portraits concern individuals or pairs who appear isolated or estranged from one another, others capture intimate, sensitive relationships between same-sex couples.

New Identities

The tumult of the Weimar Republic made it a breeding ground for new social identities. The liberated “New Woman” rejected traditional notions of femininity, choosing instead to dress androgynously, work outside the home, and exercise her newly granted right to vote. Though sexual acts between men were illegal, homosexuality, lesbianism, and transvestism were more accepted and visible than ever before, generating vibrant communities and garnering a place in popular visual and literary culture, as demonstrated by a number of books and magazines on display in the vitrines in this gallery.

August Sander’s photograph of a radio station secretary and Lotte Jacobi’s portrait of the actress Lotte Lenya immortalize the stereotypical New Woman, her hair cropped short and a lit cigarette between her fingers. Sexual identity also received frank artistic treatment, from Christian Schad’s drawing of a gay couple mid-embrace to Gert Wollheim’s gender-ambiguous lesbian couple.

Children

New Objectivity artists often turned a cold gaze onto their subjects; children were no exception. In these portraits, young boys and girls are accurately but uncannily rendered, with the suggestion that underneath their placid expressions lurks something sinister or disturbed. These are children coming of age, in the eyes of the artists who painted them, in a time characterized not by joy, play, and innocence, but by alienation and objectification—qualities that can both be read in these portraits.

The visage of Hans Grundig’s Little Boy with Red Cap, for example, is deliberately distorted, lending a sense of unease to his dispassionate gaze and polite posture; the sitter’s position at the extreme foreground of the painting, juxtaposed with the deeply receding space that extends from his side, suggests a tension between surface and depth. Otto Dix approaches the distinction between exterior and interior more literally, applying his dissective precision to the nearly transparent skin of the prepubescent Little Girl.

August Sander and Weimar Types

In 1910, when August Sander began his ambitious People of the Twentieth Century project, he envisioned a set of forty-five folios containing twelve photographic prints each, documenting the broad range of human “types” making up the social fabric of Weimar Germany. Reflecting the contemporary impulse to create order out of chaos in a time of social change, Sander’s proposed taxonomy organized his subjects according to class or profession, with sections including farmers, skilled tradesmen, women, artists, city youth, and the unemployed; the project was to culminate in a collection of images of “idiots, the sick, the insane, and the dying.”

Sander published sixty photographs from the project in his 1929 book, Face of Our Time, but in 1936, the newly empowered Nazi regime—threatened by Sander’s dignifying treatment of those social types they considered “degenerate”—banned the book and destroyed Sander’s photographic plates.

This exhibition was organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, in association with Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia.

Source: Press Release

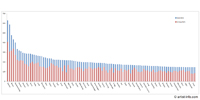

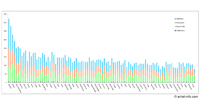

artist-info.com Exhibition Page

https://www.artist-info.com/exhibition/Los-Angeles-County-Museum-of-Art-Id379589

Exhibition Announcements

Exhibition Announcements