Artist | Antony Gormley (*1950)

https://www.artist-info.com/artist/Antony-Gormley

Artist Portfolio Catalog

Artist Portfolio Catalog

| Image | Artist | Title | Year | Material | Measurement | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

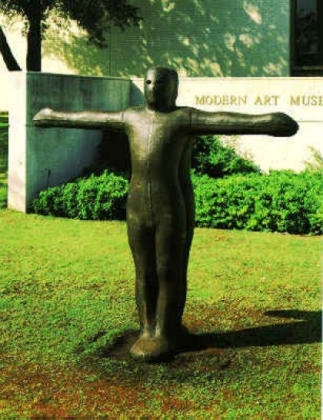

Antony Gormley | Sculpture for Derry Walls | 1987 | ductile iron and stainless steel | 7 x 96 x 43 inches | ||||||||||||||||||||

Antony Gormley (*1950)Sculpture for Derry Walls

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Biography

Biography

1950 - Born, London

Currently lives and works in London

"The quarry is itself a powerful tribute to the small bands of men that worked it, using blocks and wedges as well as the natural fissuring to cut the stone. Their technique (using neither complex machinery nor explosives) was a mixture of science, intuition and hard teamwork that is a model for us all.

Working with stone is a fine job. Working on stone in the quarry is a challenge. You have to consider the material as part of the place; as part of the earth. the joy of this project at Tout is that this very special place provides the inspiration, the material, the studio and the exhibition space."

Antony Gormley

About the work (english)

About the work (english)

What are the roots of 20th century art and how should artists relate to the past? Can our response to art transcend our own culture? Antony Gormley, Britain’s foremost sculptor and a recent winner of the Turner prize, discusses the purpose of art and much else, with Ernst Gombrich, the great art historian.

Antony Gormley: You ought to know that it was reading your book The Story of Art at school that inspired my interest in art.

Ernst Gombrich: Really!

AG: It made the whole possibility not only of studying art but also of becoming an artist a reality.

EG: That’s very flattering and very surprising.

AG: I thought we might talk about the relationship of contemporary art to art history generally: what is necessary to retain and what we can discard.

EG: I would like to start with Field (see right). I’m interested in the psychology of perception; if a face emerges from a shape you are bound to see an expression. The Swiss inventor of the comic strip, Rodolphe Tžpffer, says that one can acquire the fundamentals of practical physiognomy without ever actually having studied the face, head or human contours, but just through scribbling eyes, ears, and nose. Even a recluse, if he’s observant and persevering, could soon acquire all he needs to know about physiognomy to produce expressive faces. I have called this Tžpffer’s law: the discovery that expressiveness does not depend on observation or skill but on self-observation.

AG: For me the extraordinary thing about the genesis of form of the individual figures in Field is that it isn’t about visual appearances at all. What I’ve encouraged people to do is to treat the clay almost as an extension of their own bodies. It’s about taking a ball of clay and using the space between the hands as a kind of mould out of which the form arises.

EG: Anyone who has ever played with clay has experienced this elemental form. It has played a crucial role in 20th century art. Picasso did it from morning to night, didn’t he? He just toyed with what would come out when he created these shapes. When we loosen the constraints of academic tradition we not only create an expressive physiognomy but an expressive shape, a more independent usage; that’s what we admire in children’s drawings. The basis of our whole relationship to the world, as babies or as toddlers, is that we make no distinction between animate and inanimate things: they all speak to us, they all have a kind of character or voice. If you think back to your childhood, not only toys but most things which you encounter have this very strong character or physiognomy as "beings" of some sort. I’m sure that this is one of the roots of 20th century art, to try to recapture this. It was too exciting to discover how creative and expressive the images made by children, the insane and the untutored were. It’s no wonder that artists longed to become like little children, to throw away the ballast of tradition that cramped their spontaneity and thus thwarted their creativity. But it’s no wonder also that new questions arose about the nature of art which were not so easily answered. Deprived of the armature of tradition and skill, art was in danger of collapsing into shapelessness. There were some who welcomed this collapse—the Dadaists and other varieties of anti-artists. But anti-artists only functioned as long as there was an art to rebel against, and this happy situation could hardly last. Whatever art may be, it cannot pursue a line of resistance. If the pursuit of creativity as such proves easy to the point of triviality then there is the need for new difficulties, new restraints. I believe that it would be possible to write the history of 20th century art not in terms of revolutions and the overthrow of rules and traditions but rather as the continuity of a quest, a quest for problems worthy of the artist’s nature. Whether we think of Picasso’s restless search for creative novelty, or of Mondrian’s impulse to paint, all the modernists may be described as knights errant in search of a challenge. Would you accept this?

AG: I think it’s true that this idea of a reaction against a kind of orthodoxy is no longer a viable source of energy for art today. But I did not simply want to continue where Rodin left off; I wanted to re-invent the body from the inside, from the point of view of existence. I had to start with my own existence.

EG: I think in your art also, you are trying to find some kind of restraint. You want us to respond to the images of bodies, of your "standard" body?

AG: I like that idea of a "standard" body, but what I hope I’ve done is to completely remove the problem of the subject. I have a subject, which is life, within my own body. But in working with that I hope that it isn’t just a "standard" body: it is a particular one which becomes standardised by the process.

EG: The question is whether this internal body can be externalised. The problem starts from the most trivial fact that when we feel the cavities of our own body, let us say the interior of the mouth, we have an entirely different scale. Any crumb in our teeth feels very large and then when we get it out we are surprised that it is so small, and if the dentist belabours your tooth you have the feeling that the tooth is as large as you are. Then it turns out, if you look in the mirror, that it was an ordinary small tooth. In a sense that is true of all internal sensations: the internal world seems to have a different scale from the external world.

AG: I think that’s a brilliant, accessible example of what I’m interested in. There was a repeated sensation that I had as a child before sleep, which was that the space behind my eyes was incredibly tight—a tiny, dark matchbox, suffocating in its claustrophobic imprisonment. Slowly the space would expand and expand until it was enormous. In a way I feel that experience is still the basis of my work.

EG: In our sleep we are governed by these body sensations which we project into some kind of outside world and see as things which they aren’t. You say that in Buddhist meditation this is also so—but it isn’t. There you try to get away from thingness.

AG: What I was trying to describe was the first experience of this inner body which was in my childhood. I think then the experience of learning Vipassana with Goenka in India was much more disciplined, but was about the same thing. The minute you close your eyes in a conscious state you are aware of the darkness. With the Vipassana you explore that space systematically. First of all you…

EG: You have to learn to relax.

AG: Well, it is an interesting mixture. Anapana, or mindfulness of breathing, gives you concentration. You then use that concentration to look at the sensation of being in the body; that is a tool I try to transfer to sculpture.

EG: Yes, but my problem is how you bridge these intense experiences which we can call "subjective," and what you want the other to feel.

AG: That for me is the real challenge of sculpture. How do you make something out there, material, separate from you, an object among other objects, somehow carry on the feeling of being. In a way, where you ended in Art and Illusion is where I want to begin. The idea that there are things which can be conveyed in a material way, but which can never be given a precise word equivalent.

EG: Certainly not. Our language isn’t made like that. Our language serves a certain purpose, and that purpose is orientation of oneself and others in the three- dimensional world. But I cannot describe the feeling I have in my thumb right now, the mixture between tension and relaxation. Sometimes if you go to the doctor you feel this helplessness in describing what your sensations are, there are no words. That is an important part of all human existence, that we have these limits. But your problem as far as I see it is to transcend these limits.

AG: I want to start where language ends.

EG: But you want to make me feel what you feel.

AG: But I also want you to feel what you feel. I want the works to be reflexive. So it isn’t simply an embodiment of a feeling I once had… It’s a meeting of the expressiveness of me, the artist, and the expressiveness of you, the viewer. For me the charge comes from that confrontation. It can be a confrontation between the movement of the viewer and the stillness of the object, which is an irreconcilable difference, but also an invitation for the viewer to sense his own body through this moment of stillness.

EG: In other words, what in early textbooks was called "empathy"—a feeling that you share in the character of a building, or a tree, or an animal. I am always interested in our reaction to animals, because we react very strongly. The hippopotamus has a very different character from the weasel, there is no doubt; we also talk to them in different ways.

AG: I think that you are saying two things there. One is the anthropomorphising of external stimuli and the other thing, which I am more interested in, is the idea of body size, mass; that a hippopotamus is huge and has rather a simple body shape, and a weasel is like a line and sharp. I am trying to treat the whole body in the same way as perhaps portrait painters in the past have treated the face. I am trying to use the body as a medium.

EG: It is not self-expression.

AG: I think that underlying my return to the human body is an idea of re-linking art with human survival. You have always been concerned with finding a value in art, the application of rational principles to the understanding of an emerging language, and I think that art—certainly in the earlier part of the 20th century—took a view of that history in order to validate its own vision. I think that it is more difficult to do that now. All of us are aware that western history is one history among many histories, and in some way there now has to be a reappraisal of where value has to come from. Subjective experience exists within a broader frame of reference. When you think about what happens next in art, it is very hard not to ask the question: what happens next in the development of global civilisation?

EG: I agree with you in that the value of our civilisation and the values of art are linked. One cannot have an art in a civilisation which believes in no value whatever. I think that all our response to art depends on the roots of our own culture, that is why it is quite hard to get to the root of eastern art. I also think that sometimes we can’t understand the art of our own culture just as we don’t understand the letters in Chinese calligraphy. Don’t you agree?

AG: I think that it is invariably misunderstood, certainly at first experience. But my reply to the Chinese calligraphy question is my reply to anyone who finds it impossible to understand any one artist’s work today. If there is some sympathy there, then the invitation is to get more familiar—look at the organic development of an individual language and see if that has a universal significance.

EG: The problem is how to distinguish a work of art from a crumpled piece of paper, which also has its physiognomy and its character. I think there is still a feeling of a person behind it, which adds to the confidence of the viewer, that here is an embodiment and the viewer is interested in engaging in it.

AG: Yes, that idea of purpose is embodied in the way in which something is put together, not just in its form. In some way that sense of purposefulness has to do with how clear the workmanship is, how…

EG: How manifest…

AG: Yes.

EG: It is really the "mental set" in 20th century art which is behind all these problems. You have to have a certain feel of what is going on there, otherwise it’s just an object like any other.

AG: I think that we all are very visually informed these days. Maybe classical education within the visual arts has been replaced by a multiplicity of visual images that come through computers and advertising and all sorts of sources.

EG: Then you have the weirdest forms on television (I don’t own one by the way), and the sometimes amusing shapes created for advertising or whatever else. The problem here is the limits of triviality.

AG: Yes exactly. How do you condense from this multiplicity of images, especially in sculpture, which is something still, silent, and therefore rather forbidding because it isn’t like a moving image on a screen. It is not telling you to buy something. It is something that has a different relationship to life. That for me is the challenge of sculpture now: it may have within it a residue of 5,000 years of the body in art, but it must be approachable to somebody whose main experience of visual images is those things.

EG: You want them to feel the difference between a superficial response of amusement and mild interest, and something that has a certain gravity.

AG: Yes, I think it should be a confrontation (laughs).

EG: Coming to terms with it.

AG: And through coming to terms with it, coming to terms with themselves.

EG: Yes, perhaps that is a different matter.

AG: But that question of the difference between subjective response and the object is the essence of what I’m trying to get at. For me, the idea that the space that the object embodies is in some way both mine and everyone else’s is very important—that it is as open to the subjective experience of the person looking as it is to me, the possessor of the body that gave that form in the first place.

EG: You’ll agree that everybody’s experience is likely to be a little different.

AG: Absolutely. We have moved out of the age where you would argue that, yes that is a Madonna, but, well, the drapery isn’t quite fully achieved. Today we have moved from signs that have an ascribed meaning and an iconography that we know how to judge, to a notion of signs that have become liberated. Now that has a certain annoyance factor (laughs), but it also has a certain invitation for an involvement that was not possible before.

EG: But it was with architecture.

AG: Yes that’s true. I think of my work, certainly in its first phase, as being a kind of architecture. It’s a kind of intimate architecture that is inviting an emphatic inhabitation of the imagination of the viewer.

EG: But in architecture there was the constraint of the role of the tradition and purpose of a building. This is a church, and this is a railway station, and we approach them with different expectations. The problem for every artist is to establish some kind of framework wherein the response can develop.

AG: I’m working on it. I’d like us to talk a bit more about casting.

EG: Well, did you know that it has turned out that part of Donatello’s Judith is cast from the body? It’s astonishing. I remember Rodin was charged with casting from the body, it was considered a short cut, seen as very lazy, or cheating even.

AG: Yes, there’s a negative attitude.

EG: Quite a number of posthumous busts are based on the cast of the death mask that is usually modified. But this practice is not usually condemned.

AG: Because the in-built morbidity of the death mask is in keeping with the idea of a memorial portrait…

EG: It fits into what you call the context.

AG: But the interesting thing is that idea of trace. Certainly as a child, probably the most potent portraits which affected me in visits to the National Portrait Gallery were the portrait of Richard Burton, which was a rather dark oil painting, and the head of William Blake, which was cast from life. What affected me as a child was feeling the presence of someone through the skin. It was as if something was trying to come through the surface of the skin. In a way the casting process in that instance, and I hope also in my work, is a way of getting beyond the minutiae of surface incident and instantly into that idea of presence, without there being something to do with interpretation. One of the bases of my work is that it has to come from real, individual experience. I can’t be inside anyone else’s body, so it’s very important that I use my own. Each piece comes from a unique event in time. The whole project is to make the work from the inside rather than to manipulate it from the outside and use the whole mind/body mechanism as an instrument, unselfconsciously, in so far as I’m not aware while I’m being cast of what it looks like. I get out of the mould, I reassemble it and then I reappraise the thing I have been, and see how much potency it has. Sometimes it has none; I abandon it and start again.

EG: What does the potency depend on?

AG: The potency depends on the internal pressure being registered.

EG: How much of this is subjective and how much is inter-subjective?

AG: I am interested in something that one could call the collective subjective. I really like the idea that if something is intensely felt by one individual that intensity can be felt, even if the precise cause of the intensity is not recognised. I think that is to do with the equation that I am trying to make between an individual, highly personal experience and this very objective thing.

EG: You work as a guinea pig in a test to find out if the cast affects you. If it doesn’t, you discard it.

AG: Yes, I think that has to be what I am judging when I see the immediate results of the body mould. What I am judging is its relationship to the feeling that I want the work to convey. Once I am out of it, it does become a more objective appraisal. I work very closely with my wife, the painter Vicken Parsons. Once we have defined what the position of the body will be then it is a matter of trying to hold that position with the maximum degree of concentration possible. Sometimes it’s a practical thing; the position is so difficult to maintain that the mould goes limp. I lose it, I don’t have the necessary muscular control and stamina to maintain it. More often, and more interestingly, it isn’t those mechanical things but others that are more to do with intensity, and that can have to do with how much sleep I have had or simply with how in touch I am with what we are doing. The best work comes from a complete moment, which is a realisation. I then continue to edit the work. It rarely involves cutting an arm off and replacing it with another, but it may involve cutting through the neck and changing the angle two degrees. In terms of the process, we are talking about two stages, the first stage is making the mould. Then I go into the second stage which is making a journey from this very particularised moment to a more universal one, which is a process of adding skins. In the past this has meant using different colours, to make sure that each layer was exactly the same thickness. Now I just rely on my judgement that I have reached the point at which this notion of a universal body and a particular body is in a state of meaningful equilibrium.

EG: What you describe is a little like a painter stepping back from the canvas judging it, examining it as if it were from the outside. Now I will ask you a shocking question: why don’t you just take a photograph of your body?

AG: This is a photograph; I regard this as a three-dimensional photograph.

EG: As you say a three-dimensional photograph, it could be done by holograph. Would you accept it?

AG: That wouldn’t interest me. I am a classical sculptor in so far as I’m interested in mass.

EG: Tactility.

AG: Yes, the tactility is very important and the idea of making a virtual reality for me denies the real challenge and the great joy of sculpture which is a kind of body in space.

EG: And of course it is to scale, while the photograph on the whole needn’t be and can hardly be demonstrably to scale.

AG: The other problem with a photograph is that it is a picture, and I am not really interested in pictures as I am not interested in illusion. This idea has in a way informed your book: the history of art as a succession of potential schema by which we are invited to make a picture of the world. As we evolve the visual language we continually revise the previous schema in order to find an illusion that works more and more effectively. I feel that I have left that whole issue behind. We have to find a new relationship between art and life. The task of art now is to strip us of illusion. To answer your question, how do we stop art from descending into formlessness or shapelessness? How do we find a challenge worthy of the artist’s endeavour? My reply to that is, we have somehow to acknowledge the liberty of creativity in our own time, which has to abandon tradition as a principle of validation, to abandon the tradition of mainstream western art history and open itself up. Any work in the late 20th century has to speak to the whole world.

EG: It may have to, but it won’t.

AG: Well, there is this whole question of gender and masculinity and how it relates to the idea of a universally recognisable experience. In some of my work, the sexuality is declared and relevant to the subject of the work and at other times it isn’t. I have tried to escape from the male gaze, if we are thinking about the male gaze both in relation to nature as a place of slightly frightening otherness and the male gaze in relation to the female body as the object of desire, or the object of idealisation. I think the idealisation of my work and its relationship to landscape are very different from historical models. I am aware that the work is of a certain sex.

EG: Well everybody belongs to a certain gender and a certain age, you can’t get out of that and I think it’s silly to try.

AG: Yes, but what I’m saying is that this is a modified maleness; without trying to be the orthodox new man, a lot of work tests the prescribed nature of maleness in various ways, but I can’t deny that it comes from a male body and from a male mind. Part of the reason that so much of the work tries to lay the verticality of the body down, or re-present it by putting it on the wall, is that I am aware that even when a body case is directly on the floor, because I am tall there is a sense of dominance, of a male confrontation… But I want to ask you one important question; you have done a lot for all of us in terms of making apparent the structures of our own visual culture and I get the feeling that you have a faith in the value of that story. I don’t know what your faith is in the art of now, or of the future.

EG: About the future I know nothing. I am not a prophet. About the situation at present, I think that the framework of art is not a very desirable one—the framework of art-dealing, art shows and art criticism. But I don’t think that it can be helped, it is part of destiny. Sensationalism and lack of concentration are not very desirable and not very healthy for art, but I don’t despair of the future or at least the present of art. I wouldn’t despair because there will always be artists as long as there are human beings who think that this is an important activity.

AG: But do you feel that we are at the end of the story that you wrote?

EG: No, of course not. I do feel that there is a disturbing element in the story; in the new edition I am working on the intrusion of fashions into art, which has always existed. Romanticism has created an atmosphere that makes it harder for an artist to be an artist, because there are always seductive cries or traps which may tempt the artist to this kind of sensationalism—like exhibiting the carcass of a sheep—because they are talking points. This temptation to play at talking points becomes the pivot of what the young then want to do, also to have the same talking point. I think this is a social problem rather than a problem of art.

AG: It is very difficult not to start talking about such things without sounding sententious and moralistic, but I do feel that art is one of the last realms of human endeavour left that hasn’t been tainted by ideologies. In some way art does have this potential to be a focus for life which can be removed from the constraints of moral imperative, but nevertheless can invite people to think about their own actions.

EG: It has its own moral imperatives.

AG: It does for the artist making it. I think it is very, very difficult then to transfer that degree of moral commitment.

EG: It is not all that difficult. The artist mustn’t cheat. It’s as simple as that.

AG: He must take responsibility for his own actions.

EG: If he feels, as you just said, that something isn’t good enough he must discard it. Self-criticism is part of this moral imperative, and has always been. It is the same whether you write a page or whatever you do; if it isn’t good enough, you have to start again. It’s as simple as that, isn’t it? I once said it is a game which has only one rule; the rule is that as long as you think that you can do better you must do it, even if it means starting again. From that point of view I don’t think that the situation has changed much.

AG: We keep touching on this problem of subjectivity and I don’t think we are ever going to nail it down, but we have to replace the certainties of symbolism, mythology and classical illusion with something that is absolutely immediate and confronts the individual with his own life. Somehow truth has to be removed from a depicted absolute to a subjective experience.

EG: Your faith is a very noble one. I don’t for a moment want to criticise it. The question with every faith is whether it holds in every circumstance, and that is a very different matter, isn’t it?

AG: I think the idea of style as something that is inherited and with a kind of historical development now has to be replaced by an idea of an artist responsible to himself, to a language that may or not be conscious of historical precedent.

EG: But there is a problem in your faith; would you expect from now on every artist do what you do? Surely not.

AG: No, no.

EG: Exactly, so it’s only one form of solving the problem, isn’t it?

AG: I think that we can no longer assume that simply because the right subject matter or the right means are being used that there is value in an artist’s project. I think that the authority has shifted from an external validation to an internal one and I would regard that as the great joy of being an artist. The liberation of art today is to try to find forms of expression that exist almost before language and to make them more apparent. I think that in an information age, in a sense, language is the one thing that we have plenty of, but what we need is a reinforcement of direct experience.

EG: I fear that this is a false trail; people always say: if it could be said it wouldn’t be painted and things of that kind. But language serves a very different purpose. Language is an instrument; it was created as an instrument. Cavemen said "come here" or "run, there are bison about." It is quite clear that language is an instrument. Painting a bison is a very different thing from talking about a bison. Language is in statements, art is not. Language can lie. I would say that the majority of experiences are not accessible to language, but that some are.

AG: I agree with your idea that in some way language is an orientation, but the point is that once you have oriented yourself, you then have to leap, you have to go somewhere. The question then is whether you go into the known or into the unknown.

From: Prospect Magazine; August / September 1996

Solo Exhibitions

Solo Exhibitions

1981 Solo Exhibition - Whitechapel Art Gallery (London)

1981 Solo Exhibition - Serpentine Gallery (London)

1983 Solo Exhibition - Coracle Press (London)

1984 Solo Exhibition - Riverside Studios (London/Cardiff)

1984 Solo Exhibition - Salvatore Ala Gallery (New York)

1981 85 - Salvatore Ala Gallery (New York)

1981 85 Solo Exhibition - Städtische Galerie / Kunstverein (Regensburg / Frankfurt)

1981 85 Solo Exhibition - Galerie Wittenbrink (Munich)

1981 85 Solo Exhibition - Galleria Salvatore Ala (Milan)

1986 Solo Exhibition - Salvatore Ala Gallery (New York)

1986 DRAWINGS - Victoria Miro Gallery (London)

1987 MAN MADE MAN - La Criee Halle d'Art Comtemporain (Rennes)

1987 DRAWINGS - Siebu Contemporary Art Gallery (Tokyo)

1987 VEHICLE - Salvatore Ala Gallery (New York)

1987 Solo Exhibition - Gallerie Hufkens de Lathuy (Brussels)

1987 FIVE WORKS - Serpentine Gallery (London)

1988 Solo Exhibition - Burnett Miller Gallery (Los Angeles)

1988 Solo Exhibition - Contemporary Sculpture Centre (Tokyo)

1988 THE HOLBECK SCULPTURE - Leeds City Art Gallery

1989 Solo Exhibition - Louisiana Museum of Modern Art (Denmark)

1989 Solo Exhibition - Salvatore Ala Gallery (New York)

1989 Solo Exhibition - Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Edinburgh)

1989 DRAWINGS - McQuarrie Gallery (Sydney)

1989 A FIELD FOR THE ART GALLERY OF NSW

1989 A ROOM FOR THE GREAT AUSTRALIAN DESERT - Art Gallery of NSW (Sydney)

1990 BEARING LIGHT - Burnett Miller Gallery (Los Angeles)

1991 DRAWINGS & ETCHINGS - Frith Street Gallery (London)

1991 Solo Exhibition - Galerie Isy et Christine Brachot (Brussels)

1991 AMERICAN FIELD - Salvatore Ala Gallery (New York)

1991 BEARING LIGHT - Gallery Shirakawa (Kyoto)

1991 SCULPTURE - Galerie Nordenhake (Stockholm)

1991 SCULPTURE - Miller Nordenhake (Kšln)

1991 AMERICAN FIELD AND OTHER FIGURES - Modern Art Museum (Fort Worth, Texas)

1992 AMERICAN FIELD - Touring: Centro Cultural Arte Contemporaneo (Mexico City), San

1992 Diego Museum of Cont. Art (La Jolla, CA)

1993 The Corcoran Gallery of Art (Washington DC), The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Montreal)

1993 RECENT IRON WORKS - Burnett Miller Gallery (Los Angeles)

1993 BODY AND SOUL: LEARNING TO SEE - Contemporary Sculpture Centre (Tokyo)

1993 LEARNING TO THINK - The British School (Rome)

1993 Solo Exhibition - Galerie Thaddeus Ropac (Paris) Touring : Malmö Kunsthalle (Sweden), Tate Gallery (Liverpool)

1994 Irish Museum of Modern Art(Dublin)

1994 EUROPEAN FIELD - Touring: Centrumsztuky (Warsaw)

1994 Moderna Galerija (Ljubljana), Muzej Suvremene Umjetnosti (Zagreb), Ludwig Museum (Budapest) 1995: Prague Castle (Prague)," Sala Rotunda", National Theatre (Bucharest, Romania)

1994 LOST SUBJECT - White Cube (London)

1994 FIELD FOR THE BRITISH ISLES - Touring: Oriel Mostyn (Wales), Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Edinburgh);

1995 - Orchard Gallery (Derry), Ikon Gallery (Birmingham) (with Concrete Works), National Gallery of Wales

1995 ESCULTURA - Galeria Pedro Oliveira (Porto, Portugal)

1995 DRAWINGS - PaceFoundation (San Antonio)

1995 Solo Exhibition - Kohji Ogura (Nagoya)

1995 CRITICAL MASS - Remise Museum (Vienna)

1996 - FIELD FOR THE BRITISH ISLES - Greensfield BR Works (Gateshead); Hayward Gallery (London)

1996 NEW WORK - Obela Gallery (Sarajevo)

1996 INSIDE THE INSIDE - Galerie Xavier Hufkens (Brussels)

1990 - 94 - BODY AND LIGHT AND OTHER DRAWINGS - Jay Jopling in Association with Independent Art Space (London)

Group Exhibitions

Group Exhibitions

1980 NUOVE IMAGINE – Milan

1981 BRITISH SCULPTURE IN 20TH CENTURY - Whitechapel Art Gallery (London)

1981 OBJECTS AND SCULPTURE - ICA (London) Arnolfini (Bristol),cat.

1982 FIGURES AND OBJECTS - John Hansard Gallery (London), cat.

1982 OBJECTS AND FIGURES - Fruitmarket Gallery (Edinburgh)

1982 CONTEMPORARY CHOICES - Serpentine Gallery (London)

1982 WHITECHAPEL OPEN - Whitechapel Art Gallery (London)

1982 HAYWARD ANNUAL:BRITISH DRAWING - Hayward Gallery (London), cat.

1982 APERTO '82 - Biennale de Venezia (Venice), cat.

1983 NEW ART - Tate Gallery (London), cat.

1983 VIEWS AND HORIZONS - Yorkshire Sculpture Garden (Yorkshire)

1983 THE SCULPTURE SHOW - Hayward and Serpentine Galleries (London), cat.

1983 WHITECHAPEL OPEN - Whitechapel Art Gallery (London)

1983 TONGUE AND GROOVE - Touring: Coracle Press (London), St Pauls Gallery (Leeds) Ferens Gallery (Hull)

1983 ASSEMBLE HERE:New English Sculpture - Puck Building (New York), cat.

1983 PORTLAND CLIFFTOP SCULPTURE - Camden Arts Centre (London), cat.

1983 / 84 - TRANSFORMATIONS: NEW SCULPTURE FROM BRITAIN XVIIBienal de Sao Paulo; Museu de Arte Moderna (Rio de Janiero); Museo de Arte Moderno (Mexico); Fundacao Calouste Gulbenkian (Lisbon), cat.

1984 Camden Arts Centre (London)

1984 AN INTERNATIONAL SURVEY OF RECENT PAINTING & SCULPTURE - The Museum of Modern Art (New York), cat.

1984 ANNIOTTANTA - Galleria Cimunale d'Arte Moderna (Bologna), cat.

1984 THE BRITISH ART SHOW - Birmingham, Edinburgh, Sheffield, Southampton, cat.

1984 METAPHOR AND/OR SYMBOL - National Gallery of Modern Art Tokyo), cat.

1984 HUMAN INTEREST - Cornerhouse Gallery (Manchester)

1985 WALKING AND FALLING - Plymouth Arts Centre (Plymouth); Kettle's Yard (Cambridge); Interim Art (London), cat.

1985 NUOVE TRAME DELL'ARTE - Castello Colonna di Genazzano (Italy), cat.

1985 THE BRITISH SHOW - Art Gallery of Western Austrailia, Art Gallery of NSW, Queensland Art Gallery (Australia), National Gallery, Wellington Gallery (New Zealand), cat.

1985 BEYOND APPEARANCES - Nottingham Castle Museum

1985 THREE BRITISH SCULPTORS - Neuburger Museum, State University of New York

1985 FIGURATIVE SCULPTURE - Susanne Hilberry Gallery (Birmingham, Michigan)

1986 ART AND ALCHEMY - Venice Biennale (Venice), cat.

1986 PROSPECT '86 - Frankfurt Kunstverein (Frankfurt), cat.

1986 THE GENERIC FIGURE - The Corcoran Gallery of Art (Washington DC), cat.

1986 BETWEEN OBJECT AND IMAGE - Minesterio de Cultura & British Council, Palacio de.Velasquez, Parque del Retiro (Madrid); Barcelona & Bilbao, cat.

1986 NEW ART NEW WORLD AUCTION - Jay Jopling/Charles Booth-Clibborn/Greville Wothington (London), cat.

1986 VOM ZEICHNEN: ASPEKTE DER ZEICHNUNG - Frankfurt Kunsverein, Kasseler Kunstverein, Museum Moderner Kunst (Vienna), cat.

1987 MITOGRAPHIE: LUOGHI VISIBILI/INVISIBILE DELL'ARTE - Pinachoteca Comunale (Ravenna), cat.

1987 DOCUMENTA 8 - Kassel, cat.

1987 AVANT-GARDE IN THE 80'S - Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Los Angeles), cat.

1987 T.S.W.A. 3D - City Walls (Derry, Ireland), cat.

1987 THE REEMERGENT FIGURE - Storm King Art Center (Mountainville, New York), cat.

1987 STATE OF THE ART - ICA (London), book

1987 CHAOS & ORDER IN THE SOUL - University Psychiatric Clinic (Mainz, Germany), cat.

1987 REVELATION FOR THE HANDS - Leeds City Art Gallery; Univ. of Warwick art centre

1987 THE DOCUMENTA ARTISTS - Lang O'Hara (New York)

1987 / 88 VIEWPOINT - Musees Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique (Brussels), cat.

1988 THE IMPOSSIBLE SELF - Winnipeg Art Gallery; Vancouver Art Gallery (Canada), cat.

1988 LEAD - Hirschl & Adler Modern (New York), cat.

1988 MADE TO MEASURE - Kettles Yard (Cambridge), cat.

1988 STARLIT WATERS:BRITISH SCULPTURE

1968 - 88Tate Gallery Liverpool, cat.

1988 ROSC'88 - Dublin, cat.

1988 PORKKANA-KOKOELMA - Vanhan Galleria (Helsinki), cat.

1988 / 89 - BRITISH NOW: SCULPTURE ET AUTRES DESSINS - Musee D'Art Cont. de Montreal (Montreal), cat.

1989 IT'S A STILL LIFE - Art Council Collection (South Bank Centre, London), cat.

1989 OBJECTS OF THOUGHT - Tornberg Gallery (Malmo, Sweden)

1989 CORPS-FIGURES - Artcurial (Paris), cat.

1989 VISUALIZATION ON PAPER: DRAWING AS A PRIMARY MEDIUM - German van Eck (New York)

1990 CONTEMPORARY BRITISH SCULPTORS-WORKS ON PAPER - Connaught Brown (London)

1990 GREAT BRITAIN - USSR - The House of the Artist (Kiev); The Central House of the Artist (Moscow), cat.

1990 BEFORE SCULPTURE-SCULPTORS DRAWINGS - New York Studio School (New York), cat.

1990 SAPPORO SCULPTURE GARDEN 2 - Sapporo (Japan), cat.

1990 BRITISH ART NOW: A SUBJECTIVE VIEW - British Council Show touring Japan, cat.

1990 5TH ANNIVERSARY EXHIBITION - Burnett Miller Gallery (Los Angeles)

1990 MADE OF STONE - Galerie Isy Brachot (Brussels), cat.

1991 VIRTUAL REALITIES - Scottish Arts Council touring show, cat.

1991 SCULPTURE FOR THE OLD JAIL - Spoleto Festival USA (Charleston, South Carolina), cat.

1991 INHERITANCE AND TRANSFORMATION - The Irish Museum of Modern Art (Dublin), cat.

1991 GOLDSMITHS' CENTENARY EXHIBITIONS - 1991 Goldsmiths' Gallery (London), cat.

1991 COLOURS OF THE EARTH - British Council exhibition touring India and Malaysia, cat.

1991 DES USAGES A LA COLEUR - Ecole Regionale des Beaux-Art (Rennes, France)

1992 DRAWINGS AND ETCHINGS - Frith Street Gallery (London)

1992 C'EST PAS LA FIN DU MONDE - TOURING: La Criee (Rennes); Faux Mouvement (Metz); FRAC Basse Normandie (Caen); FRAP oitou Charentes (Angouleme)

1992 ARTE AMAZONAS - TOURING: Museu de Arte Moderna (Rio de Janiero), Berlin Kunsthalle;

1994 Museum Ludvig (AAchen), cat.

1994 SCULPTURE FOR A GARDEN - Roche Court (Wiltshire)

1994 SCULPTURE IN THE CLOSE - Jesus College (Cambridge), cat.

1994 FROM THE FIGURE - BlumHelman Gallery (New York)

1994 SUMMER SHOW - Marisa del Re Gallery (New York)

1994 NATURAL ORDER - Tate Gallery Liverpool, cat.

1994 IMAGES OF MAN - Insetan Museum of Art (Tokyo); Daimura Museum (Umeda-Osaka); Hiroshima City Museum of Cont. Art, cat.

1994 DES DESSINS POUR LES ELEVES DU CENTRE DES DEUX THIELLES, LE LANDERON - Centre scolaire et spotif des Deux Thielles (Le Landeron); Offentlich Kunstsammlung (Basel), cat.

1993 VANCOUVER COLLECTS - The Vancouver Art Gallery (Canada), cat.

1993 THE HUMAN FACTOR: FIGURATIVE SCULPTURE RECONSIDERED - The Albuquerque Museum (Albuquerque, NM), cat.

1993 THE RAW AND THE COOKED - Barbican Art Gallery (London);

1994 Museum of Modern Art (Oxford), Taipei Fine Arts Museum (Taiwan), Glynn Vivian Art Gallery (Swansea);

1995 Shigaraki Ceramic Sculpture Park (Japan), MusŽe d'Art Contemporain de Dunkerque (France), cat.

1994 AIR AND ANGLES - ITN Building (London)

1994 TURNER PRIZE FINALISTS - Tate Gallery (London), cat.

1994 FROM BEYOND THE PALE - Irish Museum of Modern Art (Dublin), cat.

1994 THE ESSENTIAL GESTURE - Newport Harbor Art Museum (Newport Beach, CA), cat.

1994 ARTISTS' IMPRESSIONS - Kettle's Yard (Cambridge)/

1995 Castle Museum (Nottingham), cat.

1995 ARS 95' - Helsinki, Finland, cat.

1995 THE MIND HAS A THOUSAND EYES - Burnett Miller Gallery (Los Angeles)

1995 CONTEMPORARY BRITISH ART IN PRINT - Scottish Museum of Modern Art (Edinburgh), cat.

1995 FREDSSKULPTUR '95 - Denmark, cat.

1995 THE WELTKUNST COLLECTION: British Art of the 80's and 90's - Irish Museum of Modern Art (Dublin)

1995 ZEICHNUNGEN SAMMELN - Elisabeth Kaufmann (Basel)

1995 DIE MUSE? - Galerie Thaddaeus (Salzburg), cat.

1995 HERE AND NOW - Serpentine Gallery (London),cat.

1995 100 WORKS OF THE ART COLLECTION OF IWAKI CITY ART MUSEUM - Iwaki City Art Museum(Iwaki, Japan), cat.

1995 AFTER HIROSHIMA - Hiroshima City Musuem of Contemporary Art.(Hiroshima), cat.

1989 - 95 ACQUISITIONS Musee des Beaux-Arts (Rennes)

1996 WORKS ON PAPER - IMMA (Dublin)

1996 TATE ON THE TYNE - Laing Art Gallery (Newcastle)

1996 PROEM - Rubicon Gallery (Dublin)

1996 ENGINEERING ART - Former Swan Hunter Canteen Building, Wallsend (Tyneside)

1996 UNSIECLE DE SCULPTURE ANGLAISE - Jeu de Paume (Paris)

1997 BODYWORKS - Kettle's Yard (Cambridge), Marking Presence, ArtSway, New Forest

Public Collections

Public Collections

OPEN SPACE - Place Jean Monnet (Rennes)

IRON : MAN - Victoria Square, Birmingham

HAVMANN - 10m high black Arctic granite body form - commissioned for Skulpturlandskap

Norland (Mo i Rana, Norway)

Arts Council of Great Britain

Birmingham City Council

The Ashmolean Museum (Oxford)

British Council

The British Museum (London)

Contemporary Arts Society

Henry Moore Foundation for the Study of Sculpture

Jesus College (Cambridge)

Leeds City Art Gallery

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

Southampton City Art Gallery

Tate Gallery (London)

Victoria and Albert Museum (London)

Winchester Cathedral

Art Gallery of NSW (Sydney)

Caldic Collection (The Hague)

Caldic Collection (Rotterdam)

The Hakone Open-air Museum (Japan)

Herning Kunstmuseum (Denmark)

Irish Museum of Modern Art (Dublin)

Israel Museum (Jerusalem)

Iwaki City Art Museum (Japan)

Lhoist Collection (Belgium)

Louisiana Museum (Denmark)

Malmo Konsthall (Sweden)

Marquiles Foundation (Florida)

Moderna Museet (Stockholm)

Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles)

Museum of Contemporary Art (San Diego)

Museum of Modern Art (Fort Worth, Texas)

The National Museum of Contemporary Art (Oslo)

Neue Museum (Kassel)

Sapporo Sculpture Park (Hokkaido, Japan)

Stadt Kassel

Tokushima Modern Art Museum (Japan)

The Umedalen Sculpture Foundation (Sweden)Ville de Rennes (Rennes, France)

Walker Arts Centre (Minneapolis)

The Weltkunst Foundation (Zurich)

Publications

Publications

1981 "Antony Gormley" - Bulletin sheet, Whitechapel Art Gallery (London), Text by Jenni Lomax

1984 "Antony Gormley, Drawings From the Mind's Eye" - Riverside Studios, Hammersmith/Chapter (Cardiff)

1984 "Antony Gormley" - Salvatore Ala Gallery (Milan/New York), English and Italian Editions, Text by Lynne Cooke

1985 "Antony Gormley Drawings" - Salvatore Ala Gallery (Milan/New York)

1985 "Antony Gormley" - Stadtische Galerie Regensburg (Frankfurt Kunstverein), Text by Veit Loers and Sandy Nairne

1987 "Gormley" - The Seibu Department Stores (Tokyo), Text by Michael Newman

1987 "Antony Gormley Five Works" - Serpentine Gallery/Arts Council of Great Britain (London) Statement by Antony Gormley

1988 "Antony Gormley" - Contemporary Sculpture Centre (Tokyo). Text by Tadayasu Sakai

1989 "Antony Gormley" - Louisiana, Museum of Modern Art (Humlebaek, Denmark). Text by Richard Calvocoressi and Oystein Hjort

1992 "Antony Gormley: Learning to See, Body and Soul" - Contemporary Sculpture Centre (Tokyo). Text by Masahiro Ushiroshoji and Antony Gormley

1993 "Learning to See" - Thaddeus Ropac (Paris/Salzburg). Text by Yehuda Safran. Antony Gormley interviewd by Roger Bevan, The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Montreal). Texts by Pierre Theberge, Antony Gormley, Gabriel Orozco and Thomas McEvilly

1993 "Antony Gormley" - Konsthall Malmo (Sweden)/Tate Gallery (Liverpool)/Irish Museum of Modern Art (Dublin). Texts by Lewis Biggs and Stephen Bann. The artist interviewed by Declan McGonagle

1994 "Antony Gormley" - Moderna Galerija (Ljubljana, Slovenia) The artist interviewed by Marjectica Potrc

1994 "Open Space" - Ville de Rennes (France). Texts by Philippe Hardy.

1994 "Field for the British Isles" - Oriel Mostyn (Llandudno). Texts by Lewis Biggs, Caoimhin Mac Giolla Leith, Marjetica Potrc

1994 "Antony Gormley" - Galeria Pedro Oliveira (Porto, Portugal). Text by Andrew Renton

1995 "Antony Gormley" - Phaidon Press Monograph. Texts by John Hutchinson, Ernst Gombrich and Lela B. Njatin

1995 "Critical Mass" - StadtRaum, Remise (Wien)Text by Andrew Renton. Conversation with Edek Bartz

Exhibition Announcements

Exhibition Announcements

| Image | Opening | Closing | City/Country | Exhibition Place | Exhibition Title | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

May 26, 2013 11:30 am | Oct 06, 2013 | Bad Homburg v.d.H. | Blickachsen 1 - 11 | Blickachsen 9 | ||||||

Hans Arp, Le Pepin géant, 1937/1956, cast bronze (162 x 125 x 77 cm) Bad Homburg v.d.H. Blickachsen 1 - 11Blickachsen 9Contemporary Sculpture in Bad Homburg and Frankfurt RheinMain

[Armand Pierre Fernandez] Arman - Jean [Hans] Arp - Hanneke Beaumont - Caspar Berger - Damien Cabanes - Ricardo Calero - Richard Deacon - [César Baldaccini] César - Erik Dietman - Laura Ford - Gloria Friedmann - Antony Gormley - Camille Henrot - Sean Henry - Kenny Hunter - Fabrice Hybert - Ilya & Emilia [Ilya Josifovich Kabakov * 1933 & Emilia Kanevsky *1945] Kabakov - Claire-Jeanne Jézéquel - Dietrich Klinge - Masayuki Koorida - Luigi Mainolfi - Yazid Oulab - Jaume Plensa - Peter Randall-Page - Germaine Richier - Jean-Paul Riopelle - Stefan Rohrer - Moon-Seup SHIM - Hans Steinbrenner - JianGou SUI - Matthäus Thoma - Bernar Venet - Henk Visch - Not Vital - Michael Zwingmann - Assan Smati - Magdalena Abakanowicz - |

|||||||||||

offers / Requests offers / Requests  |

Learn more about this service |

|---|

Visualization |

Learn more about this service | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Interested in discovering more of this artist's networks?

3 easy steps: Register, buy a package for a visualization, select the artist.

See examples how visualization looks like for an artist, a curator, or an exhibition place: Gallery, museum, non-profit place, or collector.

Exhibition History

|

SUMMARY based on artist-info records. More details and Visualizing Art Networks on demand. Venue types: Gallery / Museum / Non-Profit / Collector |

||||||||||||

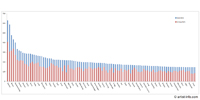

| Exhibitions in artist-info | 97 (S 44/ G 53) |

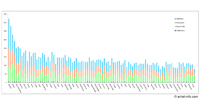

Did show together with - Top 5 of 1157 artists (no. of shows) - all shows - Top 100

|

||||||||||

| Exhibitions by type | 97: 44 / 18 / 32 / 3 | |||||||||||

| Venues by type | 69: 27 / 13 / 26 / 3 | |||||||||||

| Curators | 26 | |||||||||||

| artist-info records | Mar 1981 - Jun 2022 | |||||||||||

|

Countries - Top 5 of 13 United Kingdom (22) Germany (21) United States (9) Belgium (7) Ireland (4) |

Cities - Top 5 of 48 London (23) New York (6) Bruxelles (5) Dublin (4) Berlin (4) |

Venues (no. of shows )

Top 5 of 69

|

||||||||||

Curators (no. of shows)

Top 5 of 26

|

| Whitechapel Gallery | G | Feb 2022 - Jun 2022 | London | (417) | +0 | |

| Blazwick, Iwona (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| The Irish Museum of Modern Art - IMMA | G | Nov 2015 - May 2016 | Dublin | (207) | +0 | |

| Galerie Ropac - Paris Pantin | S | Mar 2015 - Jul 2015 | Pantin | (9) | +0 | |

| Galeria Pedro Oliveira | G | Sep 2014 - Oct 2014 | Porto | (58) | +0 | |

| Galleria Continua | G | Sep 2014 - Jan 2015 | San Gimignano - Siena | (10) | +0 | |

| Sardenberg, Ricardo (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Blickachsen 1 - 11 | G | May 2013 - Oct 2013 | Bad Homburg v.d.H. | (12) | +0 | |

| Scheffel, Christian (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Kaeppelin, Olivier (Curator) | +0 | |||||