Artist | Vicente Pascual (*1955)

https://www.artist-info.com/artist/Vicente-Pascual

Biography

Biography

Born in 1955 in Zaragoza, Spain. He held his first solo-show in 1971 at the Galeria Atenas, also in Zaragoza.

From 1970 to 1988, he worked with Angel Pascual Rodrigo in the two-man collective La Hermandad Pictorica.

In 1974 and 1975, Vicente Pascual traveled to Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Living with a Brahman family in Pushkar, Rajhastan, he studied the diverse arts and philosophies of India.

After his return to Spain in 1975, he moved to the Pyrenees.

From 1980 to 1992, Pascual’s studio was in Campanet, Mallorca. In 1992, he moved his studio to the United States.

Since 1999 Vicente Pascual lives and works in the Washington DC area.

Solo Exhibitions

Solo Exhibitions

2002 “Mundus Imaginalis”, GLOBAL FINE ART, Washington DC.

2001 "Imago Mundi", EMBASSY OF SPAIN ART SPACE, Washington DC.

2000 "Círculos/Ciclos", PALACIO DE MONTEMUZO, Zaragoza.

1999 "Romanica Similiter", MONASTERIO DE VERUELA, Veruela.

1999 "Opus Naturae 88.92", CASTILLO DE OROPESA, Toledo.

1998 "Símbolos", Galería EUDE, Barcelona.

1998 Paintings from the Exilio INSTITUTO CERVANTES, John Hancock Center, Chicago

1997 "20 Fragmentos", Sala NAVARRETE EL MUDO, Logroño.

1997 Sala IBERCAJA, Valencia.

1997 MUSEO CAMÓN AZNAR, Zaragoza.

1996 "Shields", JOHN WALDRON ARTS CENTER, Bloomington IN.

1996 Sala IBERCAJA, Guadalajara.

1996 "Archaic Echoes", SANTUARIO DE GUADALUPE, Santa Fe, NM.

1996 Galería ANTONIA PUYÓ, Zaragoza.

1995 "Nómadas", Galería EDURNE, Madrid.

1995 "Pictures from Wheresoever", IUS Gallery, New Albany IN.

1994 "Pinturas de Indiana", Galería EUDE, Barcelona.

1993 "Ancient Rhythms", IMU Gallery, Bloomington, IN.

1992 "Obra Dramática", TORREON FORTEA, Zaragoza.

1992 "Terra Incognita", CASAL BALAGUER, Palma de Mallorca.

1991 "Terra Incognita", CASAL BALAGUER, Palma de Mallorca.

1991 "Sturm und Drang", Galería MAIOR, Pollença.

1991 "A Giotto a Morandi", Galería SEN, Madrid.

1991 "Una Imatge de l’Imaginari", MUSEO DE OLOT, Girona.

1990 TORRE DE SES PUNTES, Manacor.

1989 "Ante Diem", Sala LUZÁN, Zaragoza.

1989 "Archeologica Circiter", Sala de Exposiciones de la DIPUTACIÓN PROVINCIAL, Huesca.

1989 "Bona Nit Món", Galería EUDE, Barcelona.

1988 "Al Marge del Temps", Galería FERRÁN CANO, Palma de Mallorca.

1987 "D’un Pais Daurat", Galería EUDE, Barcelona.

1987 "Retrospectiva, 70.88"; PALACIO DE SÁSTAGO, Zaragoza.

1986 Galería TORCULO, Madrid.

1985 Sala LIBROS, Zaragoza.

1985 Galería LLUCH FLUXÁ, Palma de Mallorca.

1984 Galería QUATROCENTO, Tarragona.

1984 Galería SEBASTIÁ PETIT, Lérida.

1984 Galería BENNASAR, Pollença.

1983 Galería SEN, Madrid.

1983 Galería MALONEY, Ibiza.

1983 Sala LIBROS, Zaragoza. ARCO 83 Madrid.

1983 Galería 4GATS, Palma de Mallorca.

1982 Galería BM, Granollers.

1982 Galería S’ART, Huesca.

1982 Galería EUDE, Barcelona.

1981 Galería BABEL, Vinaroz.

1981 Sala LIBROS, Zaragoza.

1980 Galería EUDE, Barcelona.

1980 Sala DOSIUNA, Barcelona.

1980 Galería CANALETA, Figueras.

1980 Galería LA BOVEDA, Borja.

1980 Galería SEN, Madrid.

1979 Galería CARMEN DURANGO, Valladolid.

1979 Galería EDURNE, Pedraza.

1978 Sala LIBROS, Zaragoza.

1978 Galería FÚCARES, Almagro.

1977 Sala VINÇON, Barcelona.

1977 Galería EDURNE, Madrid.

1976 Galería LIBROS, Zaragoza.

1976 Galería S’ART, Huesca.

1976 Gráfica 69.76, Galería BERDUSÁN, Zaragoza.

1975 Galería TASSILI, Oviedo.

1974 Galería ATENAS, Zaragoza.

1974 Sala VINÇON, Barcelona.

1974 Galería 4GATS, Palma de Mallorca.

1973 Galería S’ART, Huesca.

1972 Galería ATENAS, Zaragoza.

1972 CASA CONSISTORIAL, Aínsa.

Group Exhibitions

Group Exhibitions

2001 ART SPACE, Richmond, Virginia.

2001 PALACIO DE MONTEMUZO, Zaragoza, Spain.

2001 “Spacia” MILLENNIUM ART CENTER, Washington DC.

2000 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ARTS CENTER, Washington, D.C.

2000 Galería MORANDI, León, México.

2000 THE ELLIPSE ARTS CENTER, Arlington, Virginia.

2000 1708 GALLERY, Richmond, Virginia.

1999 Col.lecció Testimoni 98.99, Fundació LA CAIXA, Barcelona.

1998 "Europas", CASAL SOLLERIC, Palma de Mallorca.

1998 "Approaching the Millennium", AMALIA MAHONEY, Gallery, Chicago.

1997 ARCO 97 Madrid.

1996 ARCO 96 Madrid.

1996 KÖLN 96 Köln.

1995 "90 años de Arte en Aragón", Sala LUZÁN, Zaragoza.

1995 IAC 95 Namato, Japan.

1995 ARCO 95, Madrid.

1994 SURTEX’94 New York.

1994 "Col.lecció Testimoni, 93.94"; Fundació LA CAIXA, Barcelona.

1994 ART MESSE’94 Frankfurt.

1993 "Edurne de Plata", Galería EDURNE, Madrid.

1993 NEW PIER SHOW 93 Chicago.

1993 IAC 93 Namato, Japan.

1992 "Col.lecció Testimoni, 90.91"; Fundació LA CAIXA, Barcelona.

1992 "The New Spain", TOWN HALL, Galveston, TX.

1992 IAC 92 Namato, Japan.

1991 ART JONCTION 91 Nice.

1991 "Antológica", 10 Años Galería TÓRCULO, Madrid.

1990 "Vanguardia en Aragón", MUSEO DE TERUEL.

1990 "Lectures", Galería BISART, Palma de Mallorca.

1990 "100 F", Galería MAIOR, Pollença.

1990 "Col.lecció Testimoni 89.90", Fundació LA CAIXA, Barcelona.

1989 VIDEOARCO 89 Madrid.

1989 Galería EDURNE, Madrid.

1989 "De los Setenta", MUSEO DE ALAVA, Vitoria.

1988 "Col.lecció Testimoni 87.88", Fundació LA CAIXA, Barcelona.

1988 ARCO 88, Madrid.

1988 "La Estampa Contemporánea Española", CENTRO CULTURAL DEL CONDE DUQUE, Madrid.

1988 ART 19.88 Basel.

1987 "Col.lecció Testimoni 87.88", Fundació LA CAIXA, Barcelona.

1987 "25 Años de Arte Español", Sala LUZÁN, Zaragoza.

1987 CIAE 87 Chicago.

1986 "Adquisiciones Recientes", MUSEO DE VERUELA.

1986 ARCO 86 Madrid.

1986 GALERÍA AUDITORIO NACIONAL, México DF.

1985 SALÓ DE LA TARDOR, Ciutadela, Menorca

1985 CIAE 85 Chicago.

1984 "Naturalezas Muertas", MUSEO CARRILLO GIL, México D.F.

1984 ART 15.84 Basel.

1983 ARCO 83 Madrid.

1983 CIAE 83 Chicago.

1983 BIENNAL OF GRAPHIC ART, Heidelberg.

1982 "Patrimonio de la Universidad", ANTIGUA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA, Zaragoza.

1981 El Pan de cada día AYUNTAMIENTO DE ALCAÑIZ.

1981 I Salón de los 16, MUSEO ESPAÑOL DE ARTE CONTEMPORÁNEO, Madrid.

1981 BIBLIOTHEQUE MABLY, Bordeaux.

1980 AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE, New York, NY.

1980 Galería LAGUADA, Granada.

1979 MUSEU D’ART CONTEMPORANI, Ibiza.

1979 "De Goya a nuestros días", MAISON D’ESPAGNE, Paris.

1978 "Cinco Nombres", Sala LUZÁN, Zaragoza.

1978 Galería CARTEIA, Algeciras.

1978 "Trayectoria 64.78", Galería EDURNE, Madrid.

1977 "Cajas"; Galería SEIQUER, Madrid.

1977 28’eme Salon de la Jeune Peinture, MUSEE DE LUXENBOURG, Paris.

1975 I Feria de Arte Contemporáneo, LA LONJA, Zaragoza.

1974 Galería ATENAS, Zaragoza.

1973 MUSEU DE L’EMPURDA, Figueres.

1973 Galería MATISSE, Barcelona.

Museums and Corporate Collections

Museums and Corporate Collections

BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL, Madrid.

THE HISPANIC SOCIETY OF AMERICA MUSEUM, New York.

REAL CALCOGRAFÍA NACIONAL, Madrid.

MUSEO DE BELLAS ARTES, Zaragoza.

INDIANA UNIVERSITY ART MUSEUM, Bloomington.

MUSEU D’ART CONTEMPORANI, Ibiza.

MUSEU D’ART CONTEMPORANI DE PALMA DE MALLORCA.

MUSEO PABLO SERRANO, Zaragoza.

MUSEO DE ARTE CONTEMPORÁNEO, Veruela.

MUSEO DE OLOT.

MUSEO DEL DIBUJO CONTEMPORÁNEO, Larrés.

COLECCIÓN DEL GOBIERNO DE ARAGÓN.

COL.LECCIÓ DEL GOVÉRN BALEAR.

COLECCIÓN DE LA DIPUTACIÓN DE ZARAGOZA.

COL.LECCIÓ DEL CONSELL INSULAR DE MALLORCA.

COLECCIÓN DE LA DIPUTACIÓN DE HUESCA.

COLECCIÓN DEL AYUNTAMIENTO DE ZARAGOZA.

COL.LECCIÓ MUNICIPAL, Palma de Mallorca.

INSTITUTO CERVANTES, John Hancock Center, Chicago.

PATRIMONIO DE LA UNIVERSIDAD, Zaragoza.

GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY ART COLLECTION, Washington, DC.

COL.LECCIÓ TESTIMONI LA CAIXA, Barcelona.

COLECCIÓN CAI, Zaragoza.

COLECCIÓN IBERCAJA.

COLECCIÓN BANCO PASTOR, Madrid.

COLECCIÓN MAZ, Zaragoza.

COLECCIÓN CERLER DE ARTE CONTEMPORANEO, Sabiñanigo.

INDIANA MEMORIAL ART COLLECTION, Bloomington.

ARLINGTON COUNTY ART COLLECTION, Arlington, Virginia.

INTER-AMERICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK, Washington DC.

DFI INTERNATIONAL ART COLLECTION, Washington DC.

About the work

About the work

A lot of contemporary painting is “trick” painting, employing the genres of the past but sneaking radically different content into established forms. Certainly this is true of artists like Byron Kim, Ingrid Calame, and Peter Halley (as well as Mike Bidlo and Sherrie Levine, if direct quotation counts.) Each presents works that resemble simple formal or informal compositions but, by appealing to pre-established color keys in the case of Kim, the source of the images in the case Calame, or recognizable prison and pipe imagery in the case of Halley, their canvases step outside of narrow formalism.

Vicente Pascual’s paintings participate somewhat in this tendency. Since he gave up representational painting (first pop-inspired political paintings and then anti-transavantgardia landscapes), he has been working on abstract canvases that might be mere formal compositions but for their quiet appeal to the meaningful forms of traditional Medieval, Islamic, Mongol, and Tuareg art. Yet while functioning in this double way, on another level his art also constitutes a rather profound critique of such two-sided painting: the distinction between pure form and content-that-is-simply-applied-to-it is not left in place for his viewers.

When one looks at a painting by Pascual, whether an acrylic and sand-infused canvas or a painstakingly produced watercolor, one is confronted with a surprisingly well-crafted and often very tasteful object. This object presents a form, usually a very simplified one (like the centrally located circular shapes that predominate in the current series), which hooks up with the arts of traditional ornamentation. In its vastly reduced condition, however, the image slides so easily into cannon of modernism that the appeal to tradition is not obvious and can come as a kind of aftereffect. This is the duality of the painting: on the one hand a well-crafted composition that can pass as a modernist offspring (especially a child of its drive to reduction) and, on the other, an appeal to something that precedes modernism by centuries or exists alongside it but in a separate world like the art of today’s nomads. (1)

Of course, a survey of contemporary art (a walk through many of the galleries in Chelsea or Soho) reveals how easily this two-sided painting can become a manner. This is something that Pascual is aware of and resists much more than his peers. For the majority of postmodern painters, the hunt for meaning can become a second level of very light formalism; meanings are sought out and applied as simply another attribute, a feature that is arbitrary and almost decorative. (Hence the references in the canvases are usually the most light imaginable, like appeals to cosmetic ingredients or to whimsically chosen personal experiences). As against this easy method, Pascual’s painting offers the much more oppositional and on the surface anti-modern notion that a meaning might actually inhere in a form and that one meaningful form might be better than another.

Of course, the prevailing doctrines of modern art have been against this, holding to the fundamental meaninglessness of form and the arbitrariness of any meaning applied to it. For example, mid-century formalist schools of painting such as abstract expressionism and color field lived dutifully under the separation of form and meaning by embracing a kind of pure opticality. The conceptual art of Joseph Kosuth, On Kawara, and others made its peace with this distinction by placing meanings, however elaborate and crucial to their projects, outside of visual form and on the side of language. Even today’s very current conceptual painting only brings form and meaning in close proximity, like oil and water, but still honors their insolubility. Nevertheless, an essentialist undercurrent has always existed in modernism, which continued fin de siecle symbolism’s beliefs about inherent meaning. This essentialist approach has surfaced periodically, appearing in Wassily Kandinsky’s beliefs about color (an essentialism emerges after a detour through his doctrines about synesthesia), in Kasimir Malevich and Joseph Alber’s theorizing, as well as in such unlike places as Yves Klein’s spiritual associations with blueness and Robert Motherwell’s blunt appeal to the composition of pigments to insure their necessary connections to lived realities. It is this underacknowledged tradition of modernist essentialism, call it the hegemonic version’s repressed other, that Pascual appeals to when he makes paintings in which circles do stand for centering, in which tiny points represent essences and origins, and large monochrome fields denote an embracing world or cosmos.

Aware of its contrariness, Pascual’s approach connects with, at the same time as it reverses, the interests of Roger Fry, Paul Guillaume, and Wilhelm Worringer. At the beginning of the modern movement, these writers saw connections between the forms chosen by primitive man and the abstractionist tendencies of the modern world. With hindsight, we can doubt whether their views were history or fantasy, to be understood more as a comment on the so-called primitive peoples than as a projection of the modern condition, but, in any case, an affinity was perceived and recorded: tribal patterns were seen as prototypes for the geometries of the machine age, while the arts of Africa and Oceania would henceforth be investigated with newfound rigor. To be modern, these theorists believed, was to be primitive, just as primitiveness was viewed as a kind of modernism.

The relationship was not, however, as symmetrical or as reflexive as one might have hoped. A residue remained insofar as there was an inevitable one-sidedness to the interpretation (actually the colonization) of the early beliefs that is all too evident today. Pascual goes back to this originary aspect of modernism, this perhaps Archimedean point (if any exists) at its theoretical origins, and applies the primitive to the contemporary rather than the contemporary to the primitive, by practically reversing the priorities between the interpreted and analyzing culture and its intellectually passive object. The significance of the our connection with so-called primitives is then seen not as a point of merely psychological affinity, as Fry and Warringer saw it, or as physically and mentally therapeutic, but as representing, as any primitive would have believed, a superhuman or spiritually objective affinity. When early moderns took over these shapes and interpreted them according to their own psychologizing contemporary tendencies, they left as a residue the objective spiritual beliefs of the creators. It is this set of beliefs, or at least the primitives’ interest in the objectivity of what is represented by their ornamentation, that Pascual addresses and in a large measure appropriates.

For Pascual the shapes—the circles, squares and other reduced glyphs--in his paintings are forms akin to the intersubjective schemas of the understanding that Plato, Kant, and Cassirer saw as preconditioning appearances. (2) As such they are about the realities of centering, harmony, and unity that precede the abstractions of everyday life. As templates, cognitive fundamentals, they point to the fact that our notions of pure abstraction and pure realism make little sense once one accepts that furniture of the universe is richer that the visual color patches of positivism. The proof of this subject’s cogency is that it can force a rereading of the art of the past. Once one has looked at this work and accepted its premises, Mark Rothko or Adolf Gottleib’s painting appears to be involved with inchoate and haphazard playing with forms that could actually be fruitfully researched and deliberately applied. The meanings that result in Pascual’s painting are thus humbler and more robust than those that usually circulate. By actively seeking out the significances of forms that are usually treated casually, Pascual’s painting is a kind of anti-humanist project: it is both an emptying out of modernism (of its subjectivity and myths of expressiveness) but at the same time an enriching and enlarging via the appeal to a larger, prior belief system.

Pascual’s latest series is stark: its palette consisting mostly of black sumi ink and Quinacridone, colors that we can associate with his origins in desert Aragon. Many of the pieces are visible fragments with frayed, torn edges that invoke, like the Schlegel brothers’ literary fragments, the wholes of which they might be a representative part. The geometry in these works is severely simplified and represents the latest and most stringent in a set of self-imposed rules that Pascual initiated when he took over the standards of the landscape genre about twenty-five years ago. Within this highly restricted field, the artist sets out to find a liberty of discipline that is opposed to license. In his latest series, this program is inflected and perfected, with his art sounding its perennial note that invokes return and control as against innovation, and correction, repair, and refinement in lieu of unceasing chaotic cultural upheaval.

Pascual knows that austere paintings such as his require a special context in which their understated character can be read. To create this context he feels the need to exercise absolute control over the environment, the entire context of display, even his carefully designed catalogues. He mutes the wall color, dims the ambient light, and by the same token has avoided environments of display that might be too caught up in noisy commerce for his art to operate. Except for his concern to put the work first and not the environment and to eschew theatricality of all kind -and these are major reservations- Pascual could be compared to one of today’s many installation artists.

Pascual has said that the artistic gesture is for him a matter of the imposing order on chaotic nothingness. (3) This is a gesture that he desires to keep as evident as possible by not eliminating all empty spaces in the exhibition rooms and the paintings but instead keeping them present, even prominent in the finished work. His mentioning an original creative gesture may sound oddly close to unschooled primitivism of modernism (like that of action painters), but Pascual’s is as usual very far from it. His practice is informed by an awareness that “primitive art” is always the work trained and highly skilled craftsman, hence more about order than expression; like geometry, it relies on impersonal primitives that are no less beautiful for their existing before and after human existence. The effect he aims at, and very often achieves, is one in which painter and tradition speak in the same voice, where the past and present are subsumed under the unifying framework of something permanent and objective. If this is a tall order, it is one that Pascual has been working on for most of his career and his self chosen masters, the anonymous artists and craftsmen to whom he has voluntarily apprenticed himself, have pursued for many more.

By Chris Gilbert

Associate Curator at Des Moines Art Center

Washington D.C. June, 2000

1) The art of nomadic peoples became a special preoccupation of Pascual during the period 1993 to 1997.

2) The comparison is not exact, with Kant and Cassirer at least, since they were seeking epistemological fundamentals. By contrast, Pascual is interested in existential or ontological fundamentals.

3) Conversation with the artist, May 26, 2000.

offers / Requests offers / Requests  |

About this service |

|---|

Exhibition Announcements Exhibition Announcements  |

About this service |

|---|

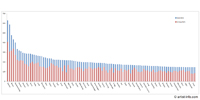

Visualization |

Learn more about this service | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Interested in discovering more of this artist's networks?

3 easy steps: Register, buy a package for a visualization, select the artist.

See examples how visualization looks like for an artist, a curator, or an exhibition place: Gallery, museum, non-profit place, or collector.

Exhibition History

|

SUMMARY based on artist-info records. More details and Visualizing Art Networks on demand. Venue types: Gallery / Museum / Non-Profit / Collector |

||||||||||||

| Exhibitions in artist-info | 12 (S 12/ G 0) |

Shown Artists - 0 of 0 artists (no. of shows) - all shows - Top 100 |

||||||||||

| Exhibitions by type | 12: 11 / 1 / 0 / 0 | |||||||||||

| Venues by type | 8: 7 / 1 / 0 / 0 | |||||||||||

| Curators | 0 | |||||||||||

| artist-info records | Sep 1990 - Jul 2003 | |||||||||||

|

Countries - Top 1 of 1 Spain (9) |

Cities - Top 5 of 6 Madrid (3) Zaragoza (3) Barcelona (2) Pollensa (2) Palma de Mallorca (1) |

Venues (no. of shows )

Top 5 of 8

|

||||||||||

|

Curators (no. of shows)

Top 0 of 0 |

| Museo of Huesca | S | Jun 2003 - Jul 2003 | Huesca | (1) | +0 | |

| Galeria Lausin & Blasco | S | Dec 2000 - Jan 2001 | Zaragoza | (1) | +0 | |

| Eude | S | May 1998 - Jun 1998 | Barcelona | (26) | +0 | |

| Galeria Antonia Puyó | S | Dec 1996 - Jan 1997 | Zaragoza | (4) | +0 | |

| Galeria Antonia Puyó | S | Jun 1995 - Jun 1995 | Zaragoza | (4) | +0 | |

| Galería Edurne | S | Nov 1994 - Jan 1995 | El Escorial | (10) | +0 | |

| Keep reading |