Artist | Karen Finley (*1956)

https://www.artist-info.com/artist/Karen-Finley

Naked with Honey

Naked with Honey

DNA Gallery, Provincetown, MA, will be hosting the peformace

"Naked with Honey"

by Karen Finley on August 18, 19, and 20th at 8 PM, 2000.

Tickets are $20 and are available for advance purchase at the DNA Gallery.

Karen will perform"Naked with Honey," a nude ballet which reconstructs the Oedipal and Electra complex in her own version of Jack Kerouacs's On the Road. The performance is a journey of psychosexual lust and dysfunctional companionship.

Karen Finley is an artist who uses the mediums of theater, performance, literature, installation, and the visual arts. She received an MFA from the San Fransisco Art Institute, and through performance, devoted herself to "effecting change in the world." Finley considers herself an artist, "working with the tradition in which there has always been subversive work." She received wide media attention in 1990 when John Frohnmayer (then the chairman for the National Endowment for the Arts) rescinded the grant that had been awarded to her.

Finley has been performing internationally since 1981, appearing at venues such as The Kitchen and the Knitting Factory in New York City, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. She has also performed at the ICA London. Karen has had writings published in The New York Times and Art Forum, and has published six books of her own work and writings.

1-900-ALL-KAREN

1-900-ALL-KAREN

Starting on President's Day, February 16, Arizona State University Art Museum is pleased to partner with Creative Time, New York City's leading public arts presenter, in launching Karen Finley's first national public performance piece, 1-900-ALL-KAREN. Every day for six months, Finley will perform a daily message that audiences across the country can access. Her phone commentary will respond to a range of topics including observations on news headlines and social injustices as well as more personal reflections on motherhood and daily life. Listeners will have a more personal experience than ever before - a virtual one-on-one look at an artist.

Inspired by America's growing fasination with the telephone as a personal, yet anonymous outlet for information and companionship, Finley has chosen to use telecommunications as a vehicle to connect to a national audience. She specifically appropriates a 900 exchange (usually associated with the charlatanism of phone sex, horoscopes, and psychics) as a venue to explore free expression. In 1990 Finley's National Endowment for the Arts grant was rescinded due to political charges of obscenity. She fought the NEA's decision and in 1992 the grant was reinstated. Since this case has just been petitioned for consideration with the Supreme Court, 1-900-ALL-KAREN will be a source of information on Karen's perspective concerning this important ruling.

1-900-ALL-KAREN was commissioned and organized by Creative Time in keeping with its continued commitment to presenting experimental public artworks that investigate the role of art and artist in our social landscape. In a step for enhanced arts partnerships, Creative Time and Arizona State University Art Museum presents 1-900 with such nationally respected institutions as the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art (Ridgefield, CT), Allen Memorial Art Museum (Oberlin, OH), Contemporary Arts Forum (Santa Barbara, CA), CSPS (Cedar Rapids, IA), Diverseworks (Houston, TX), Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (San Francisco, CA), MOCA (Los Angeles, CA), Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego (San Diego, CA), Nexus Contemporary Art Center (Atlanta, GA), Out North Contemporary Art House (Anchorage, AK) and Wagon Train (Lincoln, NE).

Karen Finley performs and exhibits extensively throughout the U.S. and internationally. Her most recent installation, entitled Go Figure and Fear of Offending, was part of the exhibition, Uncommon Sense at the Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles).

Karen is also the author of several books, her latest being Living It Up: Humorous Adventures In Hyperdomesticity published by Doubleday. She is also represented by the Thomas Healy Gallery (New York).

Biography

Biography

Karen Finley is an artist who uses the media of theater, performance, literature, installation and visual arts. She is interested in the subject first and the form second. She is motivated by social, political and personal concerns and her work communicates these concerns to her audience through whichever medium she employs.

In 1981, Finley graduated from the San Francisco Art Institute with an MFA. She began by performing and exhibiting in Bay Area clubs and art spaces, and with the rise of punk, she opened for such bands as the Dead Kennedys. She also worked and collaborated with Brian Routh (aka Kipper Kids). Finley toured the European festival circuit with her collaborative work, and her controversial performance about current German anti-Semitism at the Theatre of the World Festival in Cologne was filmed by Fassbinder.

Upon receiving an NEA grant in 1984, Finley moved from Chicago to New York City where she staged art events, curated performance happenings at clubs, and performed in the vibrant "East Village Scene." At the end of 1985, she toured the US with the solo piece, "I'm An Ass Man." The performance dealt with the themes of sexual abuse and misogynist attitudes in the lives of women from infancy through death. That same year she recorded some of her monologues to a disco beat, using the format of dance music to communicate her ideas to people who would normally not get the chance to hear her. She has recorded numerous dance records and monologues since then, including a collaboration with Sinead O'Connor. During this year, Finley also had her first solo painting show at Mo David Gallery in New York City and received a Jerome Grant which she used to create a cable television show called The Bad Music Video Show.

In December of 1986, The Kitchen in New York City produced her solo performance, "The Constant State of Desire," which dealt with the desire to control others. It received much critical acclaim, toured throughout the United States and Europe, and was subsequently published in the academic theater journal TDR the following year (and in two other books since then). She also received a Bessie Award for this work.

In January of 1988, with the help of Art Matters and NYSCA grants, Karen Finley created her first interdisciplinary piece, "A Suggestion of Madness," at PS122 in NYC. It was part play, part dance troupe, part comedy and part reality. At the end of that year, she wrote her first full-length play, "The Theory of Total Blame," a black comedy about a dysfunctional, alcoholic family that featured a cast of six. Produced in Rochester, New York City, San Francisco and Los Angeles, it was later published in 1993 by Grove Press as part of a collection of plays edited by Michael Feingold titled New American Theater.

In 1989, Finley premiered her solo performance, "We Keep Our Victims Ready," at the Sushi Gallery in San Diego. This performance, which toured extensively throughout North America and Europe, addressed people who are oppressed for political, economic, social or sexual reasons and how they are kept in the position of the victim by a white, patriarchal system. In May of 1990, the piece received much national attention when it was vilified by conservative columnists Evans and Novak. The controversy eventually led to NEA Chairman Frohnmayer's denial of Finley's grant application due to political pressure. Nominated for "Best Play of 1989" by the San Diego Theater Critics, this piece also garnered another Bessie Award for the artist.

Her first public sculpture, sponsored by Creative Time Citywide, was unveiled in New York City in 1990. A bronze casting of her poem "The Black Sheep" was attached to a concrete monolith of her own design and installed in a park at the corner of First Avenue and Houston Street where many homeless people live. She wanted to create a piece of art specifically for the homeless since most sculpture seemed to be made for the affluent and placed in uptown parks. During that same month, Finley also created an installation at Franklin Furnace in New York City entitled, "A Woman's Life Isn't Worth Much." This installation dealt with violence toward women, and consisted of murals, objects, and wall texts hand-painted by Finley. Due to the interest shown in the exhibition, the installation was extended for several months. In Chicago, she exhibited her paintings in a solo show at World Tattoo Gallery. In 1990, her first book, Shock Treatment, was published by City Lights Books. A collection of her narratives, essays and poetry, the well-received volume is now in its fourth printing, and she has done readings from it at many universities around the country.

In 1991 she had two solo exhibitions of her paintings: one at World Tattoo Gallery in Chicago and one at Rene Fotouhi Fine Art East in East Hampton, New York.

In 1991 through 1992, Finley created an installation entitled, "Memento Mori." It consisted of two rooms: "The Woman's Room," which addressed pro-choice issues and violence toward women, and "The Memorial Room," which addressed the grief felt for those who have died of AIDS and the inability of traditional memorial services to deal with that grief. The installation featured writings by Finley on the walls, while tableaux vivants portrayed rituals that related to the text. The viewer was also given rituals to perform that related to the context of the piece, thus incorporating the viewer's own experiences into the collective emotions of the installation and making him or her a participant in the creation of public art. This installation has been exhibited at Projects U.K., Newcastle, England; The Kitchen, New York City; and The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. In February 1993 it traveled to the Intermedia Arts Gallery, Minneapolis, sponsored by the Walker Art Center.

In the spring of 1992, Finley wrote a new play, "Lamb of God Hotel," that was produced at The Kitchen with financial help from NYSCA and Art Matters grants. It expanded on the concept of "The Black Sheep" and involved a cast of four outsiders whose personal suffering is caused by oppression. It also examined suicide as an option for those suffering from AIDS. It was the first play written by Karen Finley in which she did not perform.

In May of 1992, Finley received an honorary doctorate from the San Francisco Art Institute. In June of that year, Finley premiered a collaboration with avant-garde musician Jerry Hunt of Dallas, Texas. Together, they created a performance that deconstructed the variety talk-show using musical pieces, video segments and monologues, which were framed by talk-show chit-chat from the two of them. The piece was commissioned by The Kitchen with a grant from the NEA Interarts panel.

In the summer of 1992, Finley premiered her latest solo performance piece with a commission from the Serious Fun! Festival at Lincoln Center in New York City. "A Certain Level of Denial," was performed in the spirit of simple '60s and '70s style performances rather than the large scale, theatrical style that dominated the scene at the time. The subject matter included society's indifference to AIDS, homophobia in the liberal community, and injustice to women in a male-dominated society.

In the fall of 1992, at Hallwalls in Buffalo, New York, and again for Day Without Arts (December 1) at Amy Lipton Gallery in New York City, she premiered the installation, "Written in Sand." The piece consisted of a gold-painted, sand-filled room. The only illumination come from candles placed throughout the hills of sand. In what amounted to a grieving ritual, viewers were invited to take their shoes off, walk into the room, and write the name of someone that they had loved and lost to AIDS in the sand. When they finished, they smoothed the sand back over.

In 1993, Finley received a Guggenheim Fellowship to work on a new performance piece entitled, "The American Chestnut." That same year, the lawsuit in which she was involved against the NEA was settled and she was awarded her 1990 grant. However, the reversal of the decency language provision at the NEA, which the artists won at the lower level, is still being appealed by the government.

In 1993, Finley also created a new installation for Creative Time Citywide and the 42nd Street Redevelopment Corporation entitled, "Positive Attitude." A storefront installation dealing with positive visualizations for people suffering with AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma, it was on view from the summer of 1993 until the spring of 1994 at the corner of 42nd Street and 7th Avenue.

Finley's humor book, "Enough Is Enough: Weekly Meditations For Living Dysfunctionally," was published in the fall of 1993 by Poseidon Press. Turning the tables on self-help books, the author urges people to embrace rather than fight their dysfunctional qualities in order to become more in touch with themselves. The book included her own drawings, one for each meditation, that were later exhibited at Lipton/Owens Company, New York City.

In 1994, Finley exhibited a one-woman show of paintings and three-dimensional works entitled "St. Kilda" at Kim Light Gallery in Los Angeles. She also premiered a new installation at the Walter/McBean Gallery of the San Francisco Art Institute entitled, "Moral History." Using video, photography, art books, and found objects, it examined the historically male-dominated art world and the constriction of female expression in art and in everyday life, particularly in childbirth.

In November of 1994, Rykodisc released a CD version of A CERTAIN LEVEL OF DENIAL, the critically acclaimed monologue she premiered at Lincoln Center in 1992. The deluxe package includes a 48-page book of the text interspersed with reproductions of the art that Finley incorporated into the performance on stage.

Talking with Karen Finley

Talking with Karen Finley

by Christopher Busa

Karen Finley retreated to Provincetown during the summer of 1990, following highly publicized attacks by North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms, who charged that her work, involving nudity, the rights of homosexuals, and the rage of women, was "obscene." Although obscenity often plays into art's effort to say the unsayable and to confront taboos, the wide-bodied and outspoken Senator, speaking guiltlessly from the podium of a tobacco state, persuaded the National Endowment for the Arts to deny Finley a grant already recommended by the NEA peer panel. Only recently did she win a lawsuit restoring the award, and she remains embroiled in another case about what constitutes a standard of decency. The shock of the experience has hardly abated for Finley, who recalls that her first small NEA grant, coming at the beginning of her career in the early '80s, permitted her to move to New York and launch herself by performing short pieces before rowdy crowds at the Pyramid, the Cat Club, and Palladium. She is troubled that early support such as hers may be disappearing for the new generation of artists.

At alternative spaces like The Kitchen in New York and on nationwide tours, Finley began doing longer pieces such as "I'm an Ass Man," a scathing critique of the power of male desire to "colonize" the female. Her medium is her voice and body, and nudity is crucial to her work in general. Like a live model in an art class, she de-fetishizes and de-sexualizes the body.

Always seeking ways to reach audiences outside the white cube of the gallery, and to reach audiences beyond those who attend avant-garde theater, she recorded albums of her work set to dance music, including a collaboration with Sinead O'Connor, appeared in a film by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and played Tom Hanks's doctor in Philadelphia. Increasingly she has performed her pieces in prime venues throughout the U.S. and in Europe, Australia, and South America. In 1992 she premiered A Certain Level of Denial at the Serious Fun Festival at Lincoln Center in New York. Later that summer she brought the piece to Provincetown, appearing in Town Hall before a full house and leaving the audience trembling for days from the ultrasound of her projected feeling. She began naked, wearing only a hat, and speaking in a meek voice. Slowly, over the course of the performance, she clothed herself, article by article. Gradually, across the narratives of five linked pieces, the syllables of her voice grew in power as undulating patterns of emotion emerged from incantations, laments, sobs, scolds, tantrums, ritualized rants, plaintive wailings, and an audible gnashing of teeth. It seemed I was witnessing the emergence of a new category for aesthetic judgment, the bone-marrow test. She reminded us that if an artist hasn't got passion, no matter what else they have, they haven't got much.

A provocateur, not an entertainer, Finley has a way of attacking the prejudices that hobble some of us, like a kind of arthritis that limits but is not disabling. She enacts a postmodern form of Aristotelian catharsis: she irradiates an audience with volts of fear and waves of pity. Her high levels of intensity are counterpointed in performance by a minor persona, a fragile, domestic woman, speaking in a timid, questioning, even impotent voice. Present within her, vying for expression, are both a savage woman and a hollowed-out housewife. Occasionally she also invokes male voices.

Born in Chicago in 1956, Finley attended Catholic and public schools and joined the radical ranks in the nearby college town of Evanston, involving herself with the Punks for Peace movement. In the late '70s, her father shot himself and died. She saw that when the artist Chris Burden shot himself, he made art out of his wound. To her, more shocking than personal tragedies, even her father's suicide, were larger situations-homelessness, the AIDS crisis, wars-themes that drive her work.

Utilizing her voice, a few props, and fewer clothes, Finley works in an experimental genre that can be confused with theater. Trained as a visual artist, with an MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute, she got her first NEA grant for Emerging Artists in New Genres in 1983. Often she incorporates her own "static" work-bluntly urgent drawings and paintings of thickly outlined figures, scratched with legends such as "God is a woman"-into her live performances, sometimes showing slides in huge scale on a stage scrim, creating ceremonial environments that animate her various voices. She does not project herself into a role written by someone else, but rather projects herself into roles she has written for voiceless souls on the margins of society, seeking to validate feelings of the repressed or oppressed. Her performances would be acting if someone else could do them, which, to her, would be like having another artist do one's painting.

Finley speaks of her writing, in contrast to her performances, as "removing my body from my work." Many of her writings and prose poems are related to her performance pieces, a kind of spoken writing, but the writing is not a text of the performances. One of her spoken pieces, "The Black Sheep," was cast on a bronze plaque embedded in a black rock in a park for the homeless on the Bowery. Commemorating the dispossessed, it reads with brisker cadences, more anger, and as much love for humanity as Walt Whitman. This and other poetry and prose is collected in her book Shock Treatment, published in 1990 by City Lights, the San Francisco press which published Howl. Finley, who read Ginsberg's cri de coeur in 1969 when she was 13, is gratified that her own howl is added to the mainly male list of Beat poets. Enough Is Enough, published by Simon and Schuster in 1993, mimics the genre of meditation and self-help books, which Finley began reading in the wake of the NEA conflict. Her topsy-turvy instructions make a lot of sense. For example, she points out that guilt is normal, that only sociopaths do not feel guilt, and that guilt accompanies all good things, from sex to ice cream. She shows the value of meditating on the dysfunctional and how such mindfulness can lead us to link the marginal to the mainstream.

Her most recent work, The American Chestnut, utilizes the idea that the American Chestnut, a tree blighted by a disease that prevents it from reaching maturity, casts its shadow on the American housewife who strives to garden and entertain with the unattainable perfection of Martha Stewart. This is also the subject of her latest book, Living It Up: Humorous Adventures in Hyperdomesticity, to be published by Doubleday in October. The American housewife is a woman with six arms, one each for sweeping, cooking, baking, gardening, hostessing, and holding the household together. Finley once said that the way to have power as a woman was to act like a man. I wonder, if enough women do this, perhaps in another two centuries it will dawn on men that the way to have power is to act like a woman.

Christopher Busa: This winter I was surprised to read an article about your latest book contract on the front page of the business section of the New York Times. They took it seriously as a business story. Maybe it turned out well for you in the long run, since you got to keep the first advance from Crown and sell it again to Doubleday.

Karen Finley: When Crown decided not to publish Living It Up, because it offended Martha Stewart, I was disappointed. It set a precedent for publishing houses that said they can't have two opposing views under one roof, especially if one point of view earns less income than the other. They go with the more established author. At first my book was considered funny, a humor book, a parody. But on closer examination the book criticizes how women spend their days and the fact that the only place a woman can exercise creative dominion or power or decision-making is in the safe haven of domestic territory. When I critique that, the whole world caves in. We've seen similar things happen to more famous public figures, like Hillary with the baking cookies line, a simple sentence, but the whole world caved in and she's never gotten over it. That was the beginning of the end for her. She made a comment criticizing how women spent their day, and that was it. The fact that I make fun of or parody that is very threatening. It goes beyond a financial decision. It was fine at first. The attractiveness of me going with Crown, as they presented it to me, was that they published Martha Stewart and the type of genre I was parodying. I was to have access to the designers and the knowledge Crown had. People at the top of the company knew of it. They had told Martha Stewart's editors. It had been in the New York Times that I was doing this. Then a man decided not to do it. I don't know if Martha Stewart knew or not, but Martha Stewart certainly didn't say she thought this was censorship. She certainly hasn't gotten upset about it.

CB: Has she made any comments at all?

KF: She said it just isn't her business. She didn't deal with the business situations. That's how women have been taught. They are not supposed to have political thought. I think Martha Stewart is our first lady. That's why everybody is so into her. The way she's blonde, the way she looks and handles herself. Her work becomes an overgrowth, like a cancer out of control, beyond what she attempts to do. She's trying to introduce creativity into women's lives, and I wanted to parody this misuse of power.

CB: As a creative homemaker.

KF: She's smart, she went to Barnard, she has credentials. What they'd really like for Hillary Clinton is to disguise that. Martha Stewart has all the education, but she decided to stay home and bake cookies. That's why the country's all behind her. They are with the woman who has decided to stay home and bake cookies, and who has the education, and who has made money from it. I find it gross, like a tobacco company, a really bad bill of goods.

CB: A legal corruption, part of the fabric of society and sanctioned. Making quilts is like baking cookies. You saw the patchwork quilt Jenny Humphreys did where the word "cunt" is stitched into each square. She took a safe idiom, the quilt made at home before the hearth, and she used it to make a powerful statement.

KF: That piece brings up the idea of the offended. At one point this artist was called this word, and it deeply affected her. In the history of the quilt, women would put meaning in each square, using scraps of clothing their family had worn. It was the only place where a woman could get this information out. A quilt is traditionally woman's work. Using the quilt as a canvas frees that word of its power. Good art transforms pain into some compassionate attempt to understand it. I haven't talked to Jenny Humphreys, but I think she's getting people to feel the horror she felt. You get that feeling of pain when you go in front of the Vietnam Memorial. In Syracuse there is a memorial to the plane crash in Scotland-statues of women looking up to the sky, crying. They're supposed to be mothers. You can hardly look at it, it's so deep and emotional. There are things that are hard to live with, but it's important to have them present. There are very important civil rights photos. With Mapplethorpe, you have the flowers and the XYZ work. It's important to have both.

CB: In a free society people are going to be offended just by the nature of freedom. People wonder why they should be offended. They are like Jesse Helms and want to make it against the law to offend them.

KF: Right. So you're offended. You don't like something. Everything in our society is supposed to be immediate and gratifying. People think if they do some sort of exercise, they can control things. I don't think there's anything wrong with being offended. I see movies I don't necessarily like and I will examine the reason something offends me, but I don't want to get rid of it. We live in a thinking culture, and we get the shadow of the opposite, which is feeling. Just because a person has a psychology they haven't processed doesn't mean that other people have their experience. I also have no problem with bad taste. Bad taste is okay. CB: Since becoming a mother, you've been reading a lot of children's books. Do you feel you've been torn away from the hot issues of the art world by the text you are reading to your daughter?

KF: No. It's brought my eyes open. If there is a girl, she's usually by herself. It's rare to have females who are equal. In Beatrix Potter, the females are only mothers. Jemima Puddle Duck is trying to lay an egg. Growing up, Captain Kangaroo, no females, Sesame Street, no females, except Miss Piggy, and she's not even on Sesame Street. It's okay for girls to identify and look at males for models, but boys in this culture are denied access to females. They can never fantasize about wanting to be a female. Little girls can look at men and think, I'd like to be a doctor, but little boys don't look at female role models and think they would like to be like that person without it being taboo.

CB: Your daughter Violet is now two years old. She seems very well adjusted. How does an artist care for a child?

KF: She seems wonderful. I've been very conscious of the horrors in the artist's family caused by creative life. There is a fear that artists create a destructive world for people connected to them. The men chose to leave and the women chose family. My grandmother had an incredible singing voice. She headed in the direction of an opera career and decided not to pursue it because she wanted a family. She made a choice. People in our culture have either suffered from having the artist in the family, and struggled with that myth, or they have decided to be stereotypical good people and not listen to their inside, suffering for the rest of their lives.

CB: If the nature of reality for many people is hell, are you saying you wish it weren't that way?

KF: Yes, I don't think it has to be that way. I have a problem with the machismo sense of the artist. To me, it began with Gauguin. He had to make that choice about leaving his family and going to Tahiti. He couldn't be creative in France in his family structure, but he could in a primitive place. I have a lot of problems with that, and with the super-artist, whether it's Picasso, and he-mostly it's been "he"-embodies creativity for all of us, like a voice from God. We look and stare at their art. We stare at their madness, their willingness to risk all in their personal life, and go through alcohol and women, to come up with this oil painting. In some ways it's humorous. I mean, it's just a painting. Yet the artist has to embody some ceremony. Their personal life must be deep and hectic and they must be doing it for us. It's a weird archetype we've made.

CB: You are not a male artist-maybe that has made you free.

KF: A lot of male artists are changing, too. One reason the far right is so against the artist, right now, is that artists are integrating.

CB: Isn't that the thing, that artists now stand for sanity and health?

KF: Besides the madness that artists were supposed to embody, for many years artists only came out of affluence. I just came back from Brazil, where I really felt the difference between low and high art, for lack of a better term, or folk art as opposed to art that comes from some European reference. When I went to the museums, there was no one there-very few visitors. That was interesting to me. It got me thinking about how art wasn't doing its job in Brazil. The wealthy, the businesses, try to have a European form. I haven't been there for the Bienal, but what I saw wasn't happening. I went to a sculpture park. There was no one there. But go to a park downtown, there are over 1000 people, much activity. That made me think of art in everyday life. People should be able to value what they do as art, whether they spend 15 minutes or live the Western notion that in order to be an artist work has to be nonstop, no sleep, 15 hours, draining one's soul to get to something. A size element goes along with it. I question that. It makes art very lonely, makes it so certain people can't do art. When I was pregnant, I saw how art was valued by length of time and that was connected to how I felt about art in Brazil.

CB: The populace there was participating in the pleasure of making things in little pockets of time, and that's the important thing to focus on?

KF: Braiding a child's hair is a beautiful sculpture. Setting a table. We have a value system that isolates people from being a participant in creative life, because it can't be acknowledged or recognized that everyday life is creative. That makes you feel less valuable. A woman with her vanity table, with all her things around, that's art-making.

CB: A huge amount of life takes place domestically, and if that's excluded, art is less. In fact, your new piece, American Chestnut, is performed through the character of a housewife. As I hear the voice in your performances, I think, "Who is speaking?" Very often there is a dialogue, for example, in A Certain Level of Denial, between a female patient and a white, male psychiatrist. They are distinguished by vocabulary, intensity, point of view, but essentially I feel you are pulling from different parts of your personality. Sometimes you do this very quickly, shifting from being the oppressor to being a victim, from being a leper to being a person calling someone a leper. Are you conscious of that?

KF: I think it's unconscious, but when I look at it I can explain it.

CB: The last poem of Shock Treatment, "The Black Sheep," was placed as a piece of public sculpture in a forsaken area of the East Village. You wrote that even if black sheep are outsiders in their own family, they can be family to strangers. Are you a black sheep or are you merely speaking for black sheep?

KF: Recently I feel like a black sheep. "The Black Sheep" came about from reading religious texts. I began to think that "The Lord Is My Shepherd" is not my prayer. I wanted to write a new prayer, "The Black Sheep." In it was the idea that you do not ever feel you fit in. It could be the artist, it could be the lower class. Their struggle connected them to other black sheep. That is the family. You realize this pain. I think that's an important prayer, having that realization and that acceptance. I have an image at the end, "silence at the end of the phone," which is about the attempt to have a conversation with a family member or someone that you feel is supposed to love you, and they never do. In our life certain people never love you, although you love them and they're supposed to love you.

CB: I can see how you might see yourself as a black sheep, but you don't focus on yourself, you focus on many other black sheep. What is remarkable is the range of sympathy in your imagination.

KF: If I have anything that's happened to me I just use that, turning whatever pain I have into being more compassionate to others. Imaginative sympathy, I don't think is that hard. It was very difficult to see the poverty, the visible suffering, in Brazil. When I was performing I started breaking down and telling the people I didn't know how they could endure all the poverty.

CB: What piece did you do there?

KF: A Certain Level of Denial. They want me to come back. I'm going to do a public sculpture, an installation. I'll do something with the poverty.

CB: You are making visual art, you are writing your own performance texts, poetry and prose, and you are performing or acting. How are you finding your center? Is it through the writing, is it through the image, is it through the feeling or the action of acting?

KF: It's like being in a garden and visiting the different parts of the garden. You have to have some flowers that grow in the shady part, you have to have some that grow in the sunny part. Like a conceptual artist, I always come up with a concept first, then I try to think of what structure suits my idea. Sometimes I will be doing visual elements and then, while I'm doing the visuals, the writing comes along with it. I'm a fairly slow writer. Ideas come quickly, and I work every day, but I look for something else besides working from nine to five. I don't force it, although I was schooled in a painting tradition where you're supposed to stay in the studio until something happens. You don't leave till something does. Like a jail.

CB: In sports they say, "No pain, no gain."

KF: It is like sports. I guess the reason I could never play sports was that I was not very competitive. I am not a competitive person. I liked the physicality of sports, but the idea of winning was uncomfortable for me. Men are trained, or it's in their genes. I get bored easily. When I first started performing in theaters, I felt I was appropriating a theatrical structure. I get into a problem with a medium when I start to entertain the idea that I should be taken seriously in that medium. When I did music, I never thought of myself as a rock-and-roll person, but I was appropriating the form of dance music. Once I start thinking I'm going to be doing it seriously, it falls apart. One reason I wanted to publish my book, Shock Treatment, with City Lights was because of their tradition of male Beat poets. I wanted to have a woman in the back with their listings. I've done that book, but I don't feel now I'm writing Beat poetry. With Enough Is Enough, I appropriated the medium of self-help books.

CB: In what genre did you see yourself writing in Shock Treatment?

KF: All my performance pieces, I think, are a type of poetry. I won't say the model was performance texts, because I don't give any explanations. I do that purposely. When you read a play, there's a distancing, and I wanted my book to be more immediate, the way I was moved, transformed, by reading early books like Howl and Ferlinghetti and Beat work when I was 13 years old. Everything I read then was male-based on an unconscious level. I wanted to contribute a feminine position.

CB: What are you reading now?

KF: A lot of facts, rather than expressive stuff. I read biographies. Right now I'm reading cookbooks. In my new book I take the pursuit of an unattainable domesticity that you see in Martha Stewart.

CB: If I were Martha Stewart, I'd be quaking in my Wellingtons. How many lawsuits do you have going now?

KF: I think I have five lawsuits, all involved with my art. Meanwhile, I can't wait to paint my dining room, to try to make it more like a tiki room. I think men feel this too.

CB: I love nestbuilding.

KF: I wrote Living it Up for men too. I feel I can't be taken seriously and given respect in the outside world, but within the home I can. That's where women can actually have their creativity. There's this hyper-domesticity, and a need for it, even by professional women who resort to it perhaps because they have come to a glass ceiling. In Marcia Clark or Hillary Clinton we've seen this. It's also kind of gross and extravagant to be making things with hydrangeas and dried macaroni with what's going on in Bosnia. It's like Nero playing the violin. The country is falling apart while people have a preoccupation with things fleeting and time-consuming. The positive side is the making of things. I didn't put this in American Chestnut, but I originally had a makeover of Hillary, showing her what she should do. She would have to be on the cover of Good Housekeeping, not Harper's or the Atlantic Monthly. Talking about child care is good, but talking about cookies is where it's at.

CB: Your voice in performance has an incantatory way of gaining momentum. You work the material until it becomes kneaded and shaped and understood.

KF: I shift a lot. I have conversations with myself and take one position, then another. I like to analyze and I love hindsight. I also like to look at omens, things speaking to me that aren't about language. If I come out of a meeting and something happens synchronistically, that's important to me.

CB: If the whistle blows at noon when you start your car.

KF: Yes, I look at that as important information for telling me what's really happening, an indicator, rather than an intellectual process, like synchronicity.

CB: We need to get some sense of what drove you to become a performance artist. You got your MFA in '82, but you had started performing earlier in 1979, before you got you MFA. I wanted to ask you about your father's suicide, if that's not an off topic.

KF: No.

CB: He committed suicide in 1978 and you began performing shortly afterwards?

KF: I had been doing performances since puberty, early teens, and happenings in high school, and going to the San Francisco Art Institute. So it was part of my language, though I wasn't sophisticated. I was reading Artforum about the things at the Kitchen. I'd read about Chris Burden and Vito Acconci. I was interested in artists who were doing happening type of work.

CB: Allen Kaprow?

KF: Very much so. His early work seemed wild. When I was in high school, around 14, I would take on individual quests, quietly done. I would sit on a train and write to the person next to me. I would let the letter sit there and see what they would do.

CB: Would you leave it there when you left?

KF: No, I would leave it on my lap. I would write, "Dear lady in the blue coat sitting next to me." People could be physically touching each other but have no communication. I would go in front of restaurant windows, while people were eating, and start having fits. I was interested in doing fits. I quit a job, telling them extraordinary personal information that wasn't true. I was curious about people saying they were interested in you when they were not really interested.

CB: What kind of outlandish thing did you say-that you were born in an orphanage?

KF: I told them I was pregnant. Once I pretended I had an epileptic seizure while I was a waitress. At the time, people did outlandish things. I lived in a town, Evanston, home of Northwestern University. I'd been in two riots or demonstrations. I was active in the peace movement, civil rights, all the different movements that were going on. I was outlandish in the way I dressed. I wore costumes. I came dressed as a tree. I was active at being a young person, definitely an individual. You see me now, but I was more flamboyant at that age.

CB: I read an interview you did eight years ago with David Ross and Trevor Fairbrother in which you speak about your father's jazz playing and him beating the drums and going into a trance, and you going into a trance listening to him. It made me think of the elaborate conversation you have going between the various parts of yourself, each taking different positions, and sometimes only appearing as fragments of voices, mixtures of voices. It would be wonderful to imagine you as existing in a free state, witness to your own uncensored mental activity. I suppose I am trying to say that there is something mediumistic about the way you work, the way you allow yourself to function as a conduit for a lot of emotional energy.

KF: Well, I worked as a psychic, professionally. I also feel that the performance I did here in Provincetown, A Certain Level of Denial-in that piece I am definitely visited by spirits. Things happen on stage that are unexplained. I feel very strong about the medium aspect. Sometimes I do automatic writing, sometimes I have visitations. I do feel I am a medium. I stopped doing that professionally because I couldn't do my art and also work as a psychic. When you talk about the jazz or the trance aspect and the connection to voices, I can say that several things got me interested in voices. When I was about 12 years old I had this incredible slumber party at my house. Witnessing the Chicago Democratic Convention and the riot that happened afterwards, the police attacking the demonstrators-seeing that live on television-had a tremendous effect on me. Having the Chicago Seven trial happen. Abbie Hoffman, Bobbie Seals, William Kunstler, made you think about how art was a communication of ideas, more important than the decorative. That had a big effect on me. Also, speakers. I remember being moved by the speaker when we would go to demonstrations or rallies, that being a moment when everyone knew what they were there for and the speaker bringing the passion together. There are speakers that all of us know, whether it's King or Jesse Jackson or Kennedy, incredible speakers.

CB: I hadn't thought of that connection of performance to speeches at political rallies. In making a distinction between performances and actions, Peter Hutchinson told me that he doesn't do performances, but he does do actions, meaning that the performance is done before an audience while an action is done in solitary activity or with a single assistant. I think it is a pretty useful idea.

KF: I think that is a useful idea.

CB: I would like to find some language to describe the feeling I have, watching you perform, that I am observing not a theatrical performance, so much as a private action.

KF: What I do is ceremony. It would be acting if someone else could do my performances. People ask me, and it makes me reluctant to publish my work because people feel they can do someone's performance, which to me is like someone saying, "Oh, can I do your painting?" Coming from the late '70s and doing performance work, I understand that distinction with the action. I first started doing actions where there would be few people and I would document them, but what happened was I made a conscious decision that I wanted to present work-and I'm going to use the word conceptual, I'm going to use the word avant-garde, you know, experimental-to the mass public. The person in the grocery store did not know what conceptual performances were. I wanted a language that had an effect on mainstream culture. I don't want to change so much that I have my work on HBO. I'm probably a step closer to HBO than Joseph Beuys is, but I'm still not on HBO. He is closer to PBS than me. I want to do my new piece, American Chestnut, in a white space.

CB: A white cube?

KF: Yes, like a gallery rather than a black box, which is more theater. I am concerned that people think performance is something that's like comedy. That's why I want to pull back. Another reason is that the art institutions in this country, and even in the world, have not supported action artists. I haven't talked to Chris Burden, but he's doing sculpture now. Vito Acconci is doing sculpture. These artists weren't supported. And I don't get asked to do things by too many museums. I'd like to do my performance work in museums. Overall, you don't see new genre or expanded forms promoted by the art world and the art magazines and the critics. I've been lucky. I get a lot of good reviews, but I can lose, especially with my new piece. It won't catch on if you have just worked with theater. When I was squirting milk out from my breasts, I was trying to do an abstract painting like Pollock in that famous film.

CB: The Hans Namuth film?

KF: Yes. Those are the references with it. So it's difficult and that's a reason why.

CB: Pollock said, "I am nature."

KF: I am nature, too!

CB: I was just thinking that.

KF: That's hysterical. I'll remember to use that with the Christian Coalition.

CB: There's the story of when Hofmann came to Pollock's studio, looked at the work, and said, "You don't paint from nature." And Pollock said with utter devastation, "I am nature."

KF: Oooh, I'm going to say that.

CB: Nudity is natural. When you did your show in Provi

offers / Requests offers / Requests  |

About this service |

|---|

Exhibition Announcements Exhibition Announcements  |

About this service |

|---|

Visualization |

Learn more about this service | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Interested in discovering more of this artist's networks?

3 easy steps: Register, buy a package for a visualization, select the artist.

See examples how visualization looks like for an artist, a curator, or an exhibition place: Gallery, museum, non-profit place, or collector.

Exhibition History

|

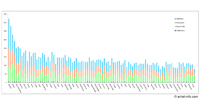

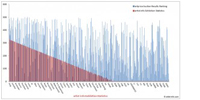

SUMMARY based on artist-info records. More details and Visualizing Art Networks on demand. Venue types: Gallery / Museum / Non-Profit / Collector |

||||||||||||

| Exhibitions in artist-info | 13 (S 8/ G 5) |

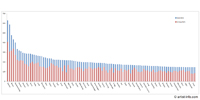

Did show together with - Top 5 of 996 artists (no. of shows) - all shows - Top 100

|

||||||||||

| Exhibitions by type | 13: 7 / 3 / 3 / 0 | |||||||||||

| Venues by type | 12: 6 / 3 / 3 / 0 | |||||||||||

| Curators | 9 | |||||||||||

| artist-info records | Jun 1992 - Dec 2013 | |||||||||||

|

Countries - Top 3 of 3 United States (11) Austria (1) France (1) |

Cities - Top 5 of 7 New York (6) Los Angeles (2) Phoenix (1) Philadelphia (1) Paris (1) |

Venues (no. of shows ) Top 5 of 12 | ||||||||||

Curators (no. of shows)

Top 5 of 9

|

| Forum Stadtpark | G | Nov 2013 - Dec 2013 | Graz | (17) | +0 | |

| Hauer, Veronika (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Alexander Gray Associates | G | Feb 2010 - Mar 2010 | New York | (65) | +0 | |

| Centre Pompidou - Musée National d'Art Moderne | G | May 2009 - Feb 2011 | Paris | (144) | +0 | |

| Morineau, Camille (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Debray, Cécile (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Bajac, Quentin (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Guillaume, Valérie (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Lavigne, Emma (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Alexander Gray Associates | S | Oct 2007 - Nov 2007 | New York | (65) | +0 | |

| Venetia Kapernekas Fine Art | S | Feb 2006 - Mar 2006 | New York | (6) | +0 | |

| DNA Gallery | S | Aug 2000 - Aug 2000 | Provincetown | (5) | +0 | |

| Keep reading |