Artist | Christian Boltanski (1944 - 2021)

https://www.artist-info.com/artist/Christian-Boltanski

About the work (english / deutsch)

About the work (english / deutsch)

Les Suisses morts (1990) und Les Ombres (1986)

The locations that Christian Boltanski, born in France in 1944, has chosen for his two installations in the museum were not actually intended as exhibition rooms in the strict sense. Les Suisses morts (The Dead Swiss) leads us down four stairs into a room under the landing that resembles a broom cup-board. With its sparse lighting, the gloomy room immediately makes the observer feel apprehensive. Over 700 portraits photos, each behind glass, fill the wall space completely from ceiling to floor; each hangs flush with the next and each is uni-formlyframed with black cloth tape, comparable to the black lines around obituaries. The room, and its shape reflects the lattice-like structure of the pictures, forms a closed unity. Small black clamp-on lights perch in a line along the top of each wall just beneath the ceiling like diffuse spots of light. This primitive lighting in the shaft-like room reminds one of archives, storage rooms, and depots.

The portraits, and it is to these that the title refers, are all taken from the obituaries' pages of a regional newspaper in one of the Swiss cantons, namely "Le Nouvelliste du Valais", where the deceased were presented by means of a photo, often taken from one of the happiest moments of their lives. Boltanski has subscribed to this newspaper for twenty years und this subscription has resulted in a collection of portrait photos ranging from small children to very old persons. Because the pictures are cropped to fit the narrow format of the frames, for all their individuality the various people are reduced to a sort of norm: they merge to become innumerable faces, almost stereotypical, passportlike, at best snapshots from private photo albums. The photos are organized quite randomly in a sequence that merely evinces the time of their appearance in the newspaper: the artist does not impose an order of his own.

Owing to their having been enlarged, many of the photos are out of focus and no longer resemble the people they portray; indeed, they could be anybody. At the same time, they are black-and-white, as factual as the buroaucratic documentary material in an archive full of personnel files. We are more used to encountering such photos as the wanted posters that hang in post offices and police stations or as the reports of missing persons in newspapers than to seeing them in museums. In fact in Boltanski's installation it is no longer possible to distinguish the perpetrators of the crime from the victims.

However, the photos also document things past, memories of people who are admittedly dead, but, by virtue of having been captured photographically while still alive, give causeforjoyfulness. The people are both present and absent at once.

Thousands of people are both similar and dissimilar. The anonymity of the people photographed and, of course, of the photographers, engenders a quite universally valid image that grects the observer. Boltanski himself says: "The more universal the image, the more it approximates life." (C.B.) In other words, he intends the image to apply to us the observers und thus to address the meaning of life per se. The installation focuses an the observer's memories, the black-and-white photos reminding us of our own childhood, even if today we can only recollect that past via the agency of the private photo album. Les Suisse morts highlights this passage of time and the fact that we ourselves have aged. In so doing, as in the case of a memento mori, an element of melancholy arises, und what remains is the memory of that moment in time frozen in the photo. We have all experienced this in one way or another when studying photographs of relatives who we do not otherwise know. Thus, Boltanski inquires as to the meaning of life und simultaneously that of death. And the nameless portraits unconsciously set emotions free - for we feel a liking for some of the portraits whereas others leave us cold.

Although each of these photographs conceals the fate of an individual, taken as a whole their a anonymity and great number lead us to think of mass life und perhaps of the violent death of all of them. It is precisely in Germany that Boltanski's work, and he himself comes from a Russo-Jewish family, repeatedly sparks off associations of, among other things, the Holocaust. Yet, to put it naively, why did so many Swiss have to die? Boltanski has this to say: "Jews and death - the two are too obvioulsy interlinked. By contrast, the link between the Swiss and death is most tenuous, because there is no apparent reason why the Swiss should die. They are neutral and rich, the air in Switzerland is unpolluted - and yet they nevertheless all die." (C.B.) The clichéd view of the Swiss sees them as clean, orderly und wealthy - an image that is least compatible of all with that of death. Here, Boltanski makes quite conscious use o a paradox. He underscores the taboo placed on death in our society and thus violates our feeling of shame. As observers, we can only see ourselves in these everyday faces. "To my mind," Boltanski states, "in general death is one of the great issues in art." (C.B.)

Such a spatial installation also challenges our normal conception of the museum as an institution, as a collection of pictures. In Les Suisses morts preservation, contemplation and remembrance are all manifest in a special way. The portraits seem to have been stored in a depot.

Photography is but a picture of reality, an image that Christian Boltanski then in turn reproduces. Photography has long since become the preferential everyday medium adopted by everyone. Boltanski makes use of this specific aesthetics of the photographic image for the individual private pictures used have been published a thousand times in the newspaper. It comes as no surprise that from the outset of his work as an artist Boltanski has focused on the use of photography as a reflection of reality, concentrating in particular on amateur photography.

In this particular installation Boltanski resembles Andy Warhol, for he takes the existing material from the world of images found in one specific massmedium. The fact that everything is slightly out of focus owing to the photos having bee enlarged and their grisaille-like, almost painterly effect also bring to mind Gerhard Richter's use of existing photographic material.

It is again light which dominates the second, smaller chamber Boltanski has prepared - in a special way. A small "side chapel" of the Museum, originally intended as a temporary storage room for large-fonnat pictures, is now infused with a religious atmosphere produced by a row of burning tea-lights each set on a small metal console. The light emanating from these minute flames causes tiny exceptionally fragile metal figures to cast their shadows onto the room's walls. Les Ombres: the shadows, immaterial pictures that correspondingly shiver faintly in the soft flickering of the candle flames.

The mythical darkness not only prompts us to think of the liturgical context of the catholic church - for example, the illumination of icons - but also reminds one of popular superstitions, such as the realm of the dead as the realm of shadows. Boltanski draws playfully on these sacred traditions, on votive offerings, and on the theme of light and darkness. He claims, moreover, that "shadows refer to disappearance", to the inability to keep somethingfor ever. When the light of the candle is extinguished so too is the image itself. The shadow figures, gesticulating wildly with outstretched arms, spread harmless fear. Or, to put it in Boltanskis words: "The ridiculous and the tragic are never far apart.

Die toten Schweizer (1990) und Die Schatten (1986)

Der 1944 in Frankreich geborene Künstler Christian Boltanski hat für seine zwei Installationen im Museum für Moderne Kunst Orte ausgewählt, die im eigentlichen Sinne nicht als Ausstellungsräume vorgesehen waren. Das Werk Les Suisses morts (Die toten Schweizer) führt den Betrachter vier Stufen hinab in einen kammerartigen Raum unter einem Treppenabsatz. Der düstere, nur mit schwachem Licht beleuchtete Raum weckt sogleich das Gefühl von Beklemmung. Wandfüllend, von der Decke bis zum Boden, sind über 700 verglaste Porträtfotos dicht an dicht gehängt, einheitlich gerahmt mit schwarzem Textilband, mit Trauerrändern in Todesanzeigen vergleichbar. Der durch diese gitterartige Struktur geprägte Raum bildet eine in sich geschlossene Einheit. Kleine schwarze Klemmlampen sitzen wie diffuse Lichter in einer Linie als Wandabschluß unterhalb des jeweiligen Deckenniveaus. Die notdürftige Beleuchtung des schachtartigen Raumes läßt an Archive, Lagersituationen oder an Depots denken.

Die Porträts stammen - und darauf bezieht sich der Titel - aus Todesanzeigen der regionalen Schweizer Kantonszeitung "Le Nouvelliste du Valais", welche die Verstorbenen mit einem Bild zeigen, oft in glücklichsten Momenten ihres Lebens aufgenommen. Boltanski hat diese Zeitung seit zwanzig Jahren abonniert. Eine Sammlung von Porträts vom Kleinkind bis zum Greis, die bei aller Individualität durch den engen formatfüllenden Bildausschnitt sehr genormt wirkt. Unzählige Gesichter, fast stereotyp, passbildhaft, allenfalls Schnappschüsse aus privaten Fotoalben. Nach dem Prinzip des Zufalls, dem Finden der Fotovorlagen in der Schweizer Zeitung entsprechend, werden die Aufnahmen aneinandergereiht, eine vorgegebene Ordnung gibt es nicht.

Die Fotos sind zum einen durch die Vergrößerung unscharf, den Abgebildeten unähnlich, ja allgemeingültig, zum andern schwarzweiß - sachlich wie archiviertes Dokumentarmaterial von bürokratischen Personalakten. Bekannter sind solche Fotos meist aus Vermißtenanzeigen oder Fahndungsplakaten von Kriminellen auf Polizei- und Postämtern. Opfer und Täter sind in diesem Fall nicht von einander zu unterscheiden.

Die Fotos dokumentieren aber auch Vergangenes, Erinnerung an Menschen, die zwar gestorben sind; da sie aber in einem Moment ihres Lebens festgehalten sind, entsteht auch Fröhlichkeit. Die Personen sind an- und abwesend zugleich. Tausende von Menschen sind ähnlich und doch verschieden. Die Anonymität der dargestellten Personen und auch die der unbekannten Fotografen schafft ein Höchstmaß an Allgemeingültigkeit für den Betrachter. "Je allgemeiner das Abbild ist, desto näher kommt es dem Leben." (C.B.) Boltanski spricht damit vom Betrachter selbst und stellt generell die Frage nach der menschlichen Existenz. Es geht um die Erinnerung des Betrachters. Die Schwarzweißfotos lassen an die Zeit der eigenen Kindheit denken, wenn auch heute nur noch vermittelt durch das private Fotoalbum. Sie lassen die vergangene Zeit deutlich werden und das eigene Älterwerden. Einem "memento mori" vergleichbar entsteht ein Moment der Melancholie. Was bleibt, ist die Erinnerung an den durch das Foto eingefrorenen Augenblick. Jeder ist vertraut mit dieser Erfahrung durch Verwandte, die nur von Fotos bekannt sind. Boltanski stellt die Frage nach dem Leben und damit gleichzeitig nach dem Tod. Die namenlosen Porträts lösen unbewußt Emotionen aus. Manche der Abgebildeten sind uns sympathisch, andere weniger.

Hinter den Fotos steht zwar das Einzelschicksal, aber durch die Anonymität und die Vielzahl an Porträts wird ein massenhaftes, vielleicht sogar gewaltsam ausgelöschtes Leben dieser Menschen vermutet. Gerade in Deutschland löst die Arbeit von Christian Boltanski, der selbst aus einer russisch-jüdischen Familie stammt, immer wieder Assoziationen, wie die an den Holocaust aus. Warum mußten aber gerade "harmlose" Eidgenossen ihr Leben lassen, könnte man naiv fragen. "Juden und Tod - ist eine zu enge Verbindung. Schweizer und Tod liegt am weitesten auseinander, weil Schweizer eigentlich keinen Grund zum Sterben haben. Sie sind neutral, reich, die Luft ist gut - und dennoch sterben sie alle." (C.B.) Die Schweizer als Klischee von Sauberkeit, Ordnung und Wohlhabenheit lassen sich am wenigsten mit einem Todesbild vereinbaren. Boltanski arbeitet hier sehr bewußt mit einem Paradox. Er bezeichnet die Tabuisierung des Todes in unserer Gesellschaft und verletzt damit das Schamgefühl. In den Gesichtern des Alltags erkennt der Betrachter nur sich selbst. "Der Tod ist für mich generell eines der großen Themen in der Kunst." (C.B.)

Ein solches raumbezogenes Werk stellt auch eine Auseinandersetzung mit dem Museum als Institution, als Bildersammlung dar. Das Bewahren, das Besinnen, das Erinnern wird hier in besonderer Weise sinnfällig. Die Porträts sind depotähnlich abgelagert, magaziniert.

Die Fotografie ist lediglich ein Bild der Wirklichkeit, das von Christian Boltanski nochmals reproduziert wird. Fotografie ist zum alltäglichen und beliebten Medium jedes einzelnen geworden. Boltanski benutzt diese spezifische Bildästhetik. Das einzelne private Bild ist l000fach in der Zeitung veröffentlicht. Seit Beginn seiner künstlerischen Arbeit beschäftigt sich Boltanski im Umgang mit Fotografie mit der Reflexion von Realität, insbesondere mit der Amateurfotografie. Mit Andy Warhol vergleichbar, benutzt Boltanski in diesem Werk das vorgefundene Material der Bildwelt eines Massenmediums. Das Unschärfeelement durch die Vergrößerung und die grisailleartige, fast malerische Wirkung erinnert an Gerhard Richters Umgang mit vorgefundenen Bildmaterialien.

Auch im zweiten, noch kleineren Kabinett von Christian Boltanski führt das Licht in besonderer Weise Regie. In einer schmalen "Seitenkapelle" des Museums, ehemals als Zwischendepot für großformatige Bilder vorgesehen, herrscht eine geradezu sakrale Stimmung, hervorgerufen durch eine Reihe von brennenden Teelichtern auf kleinen Metallkonsolen. Das Licht ihrer Flämmchen wirft den Schatten, immaterielle Bilder, die im leichten Flackern des Kerzenscheins entsprechend leise zittern. Es sind sehr fragile kleine Figuren, die den Schatten ihre Form geben.

Die mythische Dunkelheit erinnert an liturgische Zusammenhänge der katholischen Kirche (z.B. die Beleuchtung von Ikonen), aber auch an Volks- und Aberglaube (das Totenreich wird als Schattenreich bezeichnet). Boltanski spielt mit sakralen Traditionen, mit Exvotos und dem Thema von Licht und Finsternis. "Die Schatten handeln vom Verschwinden" (C.B.), dem nicht Festhalten können. Wenn die Kerze verlöscht, verschwindet auch das Bild. Heftig mit emporgestreckten Händen gestikulierend, verbreiten die Schattenfiguren einen harmlosen Schrecken. "Das Lächerliche und das Tragische liegen nah beieinander." (C.B.)

German text by Mario Kramer / Translation by Jeremy Gaines

(Extract - Full printed version available in the Museum)

MMK - Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main

offers / Requests offers / Requests  |

About this service |

|---|

Exhibition Announcements Exhibition Announcements  |

About this service |

|---|

Visualization |

Learn more about this service | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Interested in discovering more of this artist's networks?

3 easy steps: Register, buy a package for a visualization, select the artist.

See examples how visualization looks like for an artist, a curator, or an exhibition place: Gallery, museum, non-profit place, or collector.

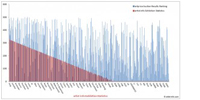

Exhibition History

|

SUMMARY based on artist-info records. More details and Visualizing Art Networks on demand. Venue types: Gallery / Museum / Non-Profit / Collector |

||||||||||||

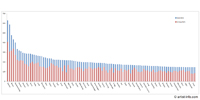

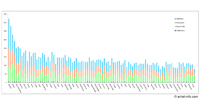

| Exhibitions in artist-info | 229 (S 52/ G 177) |

Did show together with - Top 5 of 3335 artists (no. of shows) - all shows - Top 100

|

||||||||||

| Exhibitions by type | 229: 35 / 110 / 80 / 4 | |||||||||||

| Venues by type | 164: 29 / 69 / 63 / 3 | |||||||||||

| Curators | 105 | |||||||||||

| artist-info records | Mar 1970 - Jan 2023 | |||||||||||

|

Countries - Top 5 of 24 Germany (78) France (42) United States (32) Switzerland (14) United Kingdom (9) |

Cities - Top 5 of 93 Paris (24) New York (18) Frankfurt am Main (15) Berlin (14) London (8) |

Venues (no. of shows ) Top 5 of 164 | ||||||||||

Curators (no. of shows)

Top 5 of 105

|

| Musée Félix Ziem | G | Oct 2022 - Jan 2023 | Martuges | (2) | +0 | |

| Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg | G | Mar 2022 - Jul 2022 | Wolfsburg | (71) | +0 | |

| Beitin, Andreas F. (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Broeker, Holger (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Centre Pompidou - Musée National d'Art Moderne | S | Nov 2019 - Mar 2020 | Paris | (144) | +0 | |

| Blistène, Bernard (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Tower - MMK | G | Mar 2018 - Jul 2018 | Frankfurt am Main | (10) | +0 | |

| Kunsthalle Rostock | S | Sep 2017 - Nov 2017 | Rostock | (38) | +0 | |

| The Jewish Museum | G | Sep 2016 - Feb 2017 | New York | (54) | +0 | |

| Hoffmann, Jens (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Obrist, Hans Ulrich (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Taxter, Kelly (Curator) | +0 | |||||

| Keep reading |