Artist | Alfio Giuffrida (*1953)

https://www.artist-info.com/artist/Alfio-Giuffrida

Biography

Biography

Alfio Giuffrida, Jahrgang 1953, stammt aus Catania, Italien. In Rom studierte er Malerei und Bühnenbild. Von dort aus startete er seine internationale Karriere als Maler, Bildhauer und Bühnenbildner. Seit 1986 arbeitet er in Deutschland. Im Jahr 2003 erklärte Alfio Giuffrida seine künstlerische Tätigkeit für beendet und trat als Geschäftsführer in das Unternehmen A.G. Sinnwerke ein.

Exhibitions (selection)

Exhibitions (selection)

2001 Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum, Aachen

2001 Stadtmuseum Siegburg

2004 Kunstverein Mannheim

javascript:createOnlyNewWin ('/download/museum/stadt/smausstell2001/20Skulp/index.html'

About the work (deutsch, english)

About the work (deutsch, english)

ALFIO GIUFFRIDA - RAUMGESTALTUNGEN

Der Bildhauer und Bühnenbildner Alfio Giuffrida schafft seit 1996 Stahlskulpturen, die dezidiert innovativ sind. Das Material wird zu puristischer Einfachheit reduziert. Giuffrida verwendet ausschließlich Metallrohre von 13 mm Innendurchmesser mit einer Wandstärke von 1 mm, ein Material, wie es zur Produktion von Dachgepäckträgern verwendet wird. Ebenso aus dieser Zubehörfertigung stammen zickzackförmige Verbindungselemente, die bisweilen in einer frühen Werksphase eingesetzt sind. Wurden die Skulpturen anfangs unbehandelt belassen oder durch farblosen Lack vor Patinierung geschützt, so hat der Künstler 1998 begonnen, seine Werke im galvanischen Bad hochglänzend zu verzinken. Diese sachliche Benennung des simplen Materials muss zu Beginn der Auseinandersetzung mit Giuffridas großformatigen Arbeiten stehen. Denn der Künstler vermag mit stupender Kreativität eine endlose Reihe von Formen, sogenannte Raumskulpturen und Wandinstallationen, aus dem lapidaren Werkstoff zu schöpfen.

Zentral im Werkkomplex der Stahlskulpturen steht die Lösung der großen Form. In welcher Variation Giuffrida diese Form auch biegt, stets strebt er eine über drei Meter hohe Struktur an. Die Beschreibung des Skulpturenpaars B - 731 R mag zum Exempel dienen. Vier senkrechte Elemente der Einzelstruktur übernehmen die Statik über einer rechteckigen Grundlinie bis auf etwa zwei Meter Höhe. Darüber weiten sich die Linienformen durch konvexe Drehungen und springen in der Konkave zurück. Somit entsteht eine Schulterlinie, die in einem mittigen, gedrungenen Hals endet. Statische Struktur und Schulterprofil bilden die gemeinsamen Nenner, die der Mehrzahl der sogenannten Raumskulpturen Giuffridas zu eigen sind. Die Variationsdichte, zumal in den Horizontlinien dieser Schulterprofile, lässt sich am treffendsten mit anthropomorphen Begrifflichkeiten, wie vor der Brust angewinkelte Arme (B - 707 R) Tunikaform (B - 401 R), Herzschulter (B - 981 R) oder Oberarmschulter fassen, manchmal auch in geometrischen Termini, wie Pyramidenstümpfe und Parallelogramme.

Trotz erheblicher Übermannshöhe verlieren die raumständigen Rohrskulpturen nie das menschliche Maß. Stets bieten sie Einladungen, sie zu betreten, sie mit dem eigenen Körper zu füllen und nach der äußeren Betrachtung von Innen zu sehen und von Innen zu spüren. Diese Aufforderung zu interaktiven Betätigung mit den Skulpturen verstärkt der Künstler, indem der Serien von Skulpturen in Räumen installiert. Deren interne Distanzierung wird dem menschlichen Schritt angemessen und der Betrachter zur Durchschreitung des Ganzen geradezu herausgefordert. Die Arbeit „Sechs Raumskulpturen (B - 704 UR) beinhaltet im charakteristischen Schulterhorizont eine ovale Augenform, die bei der exakten Montage als perspektivisch sich verjüngende Röhre erkennbar wird. Im langsamen Durchmessen löst sich dies Röhre wieder zu Einzelformen auf. In dieser subjektiven Erfahrbarkeit gleichen Giuffridas Raumskulpturen ephemeren Körpermodellen, die den realen Körper umschließen können oder sich in der distanzierten Ansicht zum Gedankenmodell eines Körpers entwickeln. Als solche steht die Privatikonographie Giuffridas in der gegenwärtigen Strömung des Modelldenkens. Freilich widerspricht dem Modellcharakter die flüchtig Leichtigkeit der großen Skulpturen. Deren klinisch reinen Oberflächen spiegeln die atmosphärischen Phänomene der Umwelt, also Licht, Ambientefarben, Himmelstöne wider. Diese Einbeziehung von Umgebung und Licht in die gleichsam angedeutete Skulptur zielt auch auf die Lösung eines herkömmlichen Bildhauerproblems hin, auf die Idee der schwerelosen, der schwebenden Skulptur.

Ähnliche Beobachtungen, die Erkenntnis des monumentalen Körpermodells oder die Auflösung der Skulptur im Raum, lassen sich auch an den Wandinstallationen Giuffridas treffen. Auch hier folgt der Künstler humaner Allusion im Sinne der Linie des Schulterhorizonts. Freilich sind diese Skulpturen zumeist zweidimensional, also nicht eigenständig, sondern anzulehnen. Damit ergibt sich die Variante der Licht- und Schattenwirkung. Bezeichnend wirkt der Skulpturenschatten bei diesen Arbeiten wesentlich konkreter als die Skulptur selbst, die Realität ist also ephemerer als die Virtualität. In der wandständigen Reihung können die Ensembles ebenso abgeschritten werden, wie die Raumskulpturen. Licht und Schatten werden somit zu einem Hauptmedium im skulpturalen Schaffen von Alfio Giuffrida. Je nach natürlicher, mit dem Tageslicht sich permanent verändernder und künstlicher Beleuchtung, geraten die Skulpturen im Extremfalle zur flirrenden Blendung oder zur graphischen Zeichnung. Sie erschließen sich einerseits also durch die aktive Bewegung beim Durch- oder Abschreiben, andererseits aber durch das kontemplative Betrachten der Lichtveränderung.

Die kunsthistorische Einordnung der Stahlskulpturen von Alfio Giuffrida macht deutlich, dass auch bei diesen völlige eigenständigen Arbeiten das Primat Picassos im 20. Jahrhundert vorauszusetzen ist. Mit seinen Drahtskulpturen von 1928/29 näherte sich Picasso kurzzeitig einer weitestgehenden Abstraktion an, jedoch ist durch die Implantation von Leibrundungen, Extremitäten und zumal Kopfscheiben immer die Anspielung auf das Menschenbild klar. Nur in den vorbereitenden Zeichnungen dieser Phase von 1928 verzichtet er vereinzelt ganz auf die Figürlichkeitszeichen. Diese Dessins dans l’espace, also Raumzeichnungen, die er freilich höchst selten in größere Formate umsetzen ließ, verfehlten ihre vermittelnde Wirkung auf die abstrakte Skulptur der Vor- und Nachkriegszeit, etwa auf Walter Bodmer oder Reginald Butler, und in Deutschland auf Hans Uhlmann oder Norbert Kricke, nicht. So ist normal und wünschenswert, dass auch Alfio Giuffrida diese Genialitäten kennen muss.

Alfio Giuffrida sieht seine Arbeiten nicht nur in Museen und Galerien, sondern auch als Zeichen in der Natur. In der Tat entwickelte er die schlüssige Idee, seine Skulpturen derart zu vergrößern, dass sie Hochspannungsmasten ersetzen könnte. Man stelle sich vor: Hochspannungsmasten, die ohne jede Ästhetik jedwede Landschaft weltweit durchqueren müssen und zerstören dürfen, würden von Künstlern modifiziert. Nicht mehr die rein sachliche Technik der Strommasten triumphierte über Wälder und Felder, Berge und Täler, sondern anthropomorphe Skulpturen würden in die Natur eingebettet. Diese global sicher nicht realisierbare Vorstellung böte immerhin einen Ansatz zu einer öffentlichen Kunst, der neu wäre. Technik zu ästhetisieren wurde im 20. Jahrhundert zur Normalität. Bei dem Transport von Elektrizität, der bekanntlich über längere Strecken nur oberirdisch geschehen kann, hat sich die Menschheit offensichtlich nie an der Ästhetikfeindlichkeit gestört. Giuffrida wird hier als Visionär tätig.

Alfio Giuffrida ist Bildhauer und Bühnenbildner. In seinem zweiten Beruf ist der Mensch die Voraussetzung seiner Arbeit. Nicht verwunderlich ist deshalb, dass die Allusion an das Menschenbild auch in seinem skulpturalen Schaffen richtungsweisend ist. Gleichzeitig darf der Bühnenbildner im klassischen Reich der Illusion keine gedanklichen Grenzen kennen. Der Traum von den großen Mastenbildwerken, die die flirrenden Stahlkabel über die Hügel spannen, muss geträumt werden.

Text von ULRICH SCHNEIDER

ALFIO GIUFFRIDA - SPACE DESIGNS

Since 1996 the sculptor and stage designer Alfio Giuffrida has been creating steel sculptures which are decidedly innovative. The material is reduced to puristic simplicity. Giuffrida works exclusively with metal pipes whose inside diameter is 13 mm and wall thickness is 1 mm. This material is used industrially for manufacturing vehicle roof luggage racks. Zigzag connecting elements originate from this material too and were sometimes used in an early phase of Giuffrida’s work. Initially the sculptures were left untreated or they were protected against patination by colourless varnish, but in 1998 the artist started to galvinase his works providing them with a high gloss zinc coating. This objective description of the simple material must stand at the beginning of a confrontation with and discussion of the large format works of Giuffrida, because the artist possesses stupendous creativity anabling him to produce an unlimited range of shapes and forms, so-called space sculptures and wall installations, from this seemingly uninspiring material.

The solution of the large form plays the central role in the complex of the steel sculptures. Whatever the particular variant may be, into which Giuffrida bends this form, he always strives to create a strucutre taller than three metres. The description of the pair of scultpures B - 731 R can here be taken as typical example. Four vertical elements of the individual structure play the static role over a rectangular baseline up to a height of about two metres. Above that the line forms widen through convex expansions and jump back into the concave. That gives rise to a shoulder line which ends in a central stocky neck. The static structure and shoulder profile constitute the common denominators which are typical for the majority of the so-called space sculptures created by Giuffrida. The variant profusion, particularly in the horizon lines of these shoulder profiles, can be expressed most aptly with anthropromorphic terminology such as ‘bent arms in front of the chest (B - 707 R), ‘tunica form’ (B - 401 R), ‘heart shoulder’ (B - 981 R) or ‘upper arm shoulder’. In some cases geometric concepts are applicable too, such as pyramidal frustrums and parallelograms.

In spite of their height considerably exceeding human stature, these scupltures standing in space never lose sight of human dimensions. They always offer the invitation to enter into them, to fill them with one’s own body and to see them and feel them from the inside after looking at them from the outside. The artist emplifies this enticement for interactive intercourse with sculptures by installing them in series in the rooms. Their internal spacing is adapted with respect to the human pace and forcibly challenges the viewer to walk through the whole. The work ‘six room sculpures’ (B - 704 UR) contains an oval eye shape in the characteristic perspectivistically as a tapered pipe. While stepping slowly through it, this pipe disintegrates again to the individual shapes.

In this opportunity to subjectively experience Giuffrida’s room sculptures they appear like ephemeral body models which can enclose the real body or, when viewed from a distance, can develop to become the mental model of a human body. As such, the private iconography of Giuffrida stands in the present mainstream of thinking models, even though the fleeting levity of the large structures contradicts the model character. The clinically clean surfaces reflect the atmospheric phenomena of the environment such as light, ambient colours and shades of the sky. The inclusion of the environment and light in the hinted sculpture also strives for the solution of a conentional sculptural problem, the idea of the weightless floating sculpture.

Similar observations, namely the recognition of the monumental body model or dissolving of the sculpture in space, can also be found viewing Giuffrida’s wall installations. Here too the artist pursues human allusion in the sense of the line of the shoulder horizon, although these sculptures are mostly two dimensional, so that they are leaning instead of standing on their own. This gives the variant of light and shadow effect. It is chracteristic that the sculpture shadow of these works appears considerably more concrete than the sculpture itself, so that reality is more ephemeral than virtuality. It is possible to walk through the wall sequences too, like the space sculptures.

Light and shadow thus become a principal medium in the scultpural creations made by Alfio Giuffrida. Depending on the natural illumination by daylight with its permanent diurnal changes, or artificial lighting, the sculptures become flimmering glare or a graphic drawing in the extreme situations. They reveal themselves on the one hand through active movement when walking through or along them, and on the other hand through contemplative observation of the varying illumination.

The placement of Alfio Giuffrida’s steel sculptures in the history of art makes it clear that even for these completely independant works, the primacy of Picasso in the twenthieth century is prerequisite. With his wire sculptures in 1928/29 Picasso briefly approached maximum abstraction, but the allusion to the human form was always clear through the implantation of rounded body attributes, extremities and, in particular, head disks. Only in the preparatory drawings of this phase of 1928 he occasionally abstained completely from using any figurative symbols. These designs in space, that is room drawings, which he very rarely implemented in larger formats, did not fail to have a mediating effect on abstract scultpure before and after the war, for example on Walter Bodmer or Reginald Butler, and in Germany on Hans Uhlmann or Norbert Kricke. So it is a normal and desirable expectation that Alfio Giuffrida too should know of these brilliant precursors.

Alfio Giuffrida sees his works not only in museums and galleries, but also as symbols in Nature. He even conceived the consequent idea of magnifying his sculptures to the extent that they could replace the pylons of high voltage overland transmission lines. Just imagine the high voltage lines, which have to cut across every landscape world wide and destroy it for every lack of aesthetic design, would be modified by artists. No longer the purely objective technologiy of the pylons thriumphs over forests, fields, mountains and valleys, but instead anthropromorphic sculptures would be embedded in Nature. Although certainly not globally realisable, the vision at least opens a new approach to public art. In the course of the twentieth century it has become normal practice to give technical installations an aesthetic form. But for the transport of electricity, which has to be above ground over long distances, so far evidently nobody was concerned about the non-aesthetic character of cross-continental power-lines. Giuffrida here came as visionary.

Alfio Giuffrida is sculptor and stage designer. In his second profession the human being is the prerequisite for his work. It is therefore not surprising that the allusion to the human form dominates in his sculptural works. At the same time the stage designer must not be subjected to any restriction of thought in the classical field of illusion. It is necessary to dream of huge pylon sculptures carrying glistening steel cables over the hills.

Text von ULRICH SCHNEIDER

ES KOMMT GANZ DARAUF AN

Bemerkungen zum Skulpturalen Werk von Alfio Giuffrida

Ausnahmsweise (wirklich ausnahmsweise!) ein Zitat zu Beginn: Irgendwo ziemlich am Anfang in Oscar Wildes „Dorian Gray“ steht der Satz: „Kunst spiegelt nicht die Natur, sondern den Betrachter“. Für den Fortgang der Geschichte ist dieser Satz höchst interessant, gibt er doch das Leitmotiv vor. Denn der moralische Verfall des Titelhelden wird sich in seinem Porträt widerspiegeln. Gleichzeitig spricht der große Provokateur Oscar Wilde mit diesem Satz auch gegen das Kunstverständnis seiner Zeit. Obwohl in seinem Innersten keineswegs so eindeutig vom Subjektivismus überzeugt, nimmt er doch die Pose ein und schleudert all denen, die sich als Künstler und Betrachter von Kunst dem Erschließen der tatsächlich existierenden Natur verschrieben haben, den Fehdehandschuh entgegen. Er bricht eine Lanze für die Künstlichkeit der Kunst und bestreitet all denen die Grundlage, die dem Kunstwerk im objektiven Diskurs beikommen wollen. Eine solche Position ist auch heute noch provozierend, halten doch auch wir bei aller Skepsis gegenüber den kunsttheoretischen Konzepten des 19. Jahrhunderts an der Autonomie des Kunstwerks fest. Oscar Wilde bestreitet uns diese Autonomie, denn man kann sein Diktum auch so lesen, dass Kunst nur das ist, was der Betrachter daraus macht.

„Kunst spiegelt nicht die Natur sondern den Betrachter“, das könnte auf den ersten Blick - aber nur auf den ersten Blick ein Zugang zu einer Reihe von Werkgruppen im skulpturalen Werk von Alfio Giuffrida sein. Zeichnen sich doch beispielsweise seine „Unsichtbaren Objekte“ aus dem Jahr 1999 oder die „Elemente“, die seit 1997 entstanden sind, dadurch aus, dass sie keine endgültige Form haben. Einem Kaleidoskop ähnlich besitzen sie viele, aber nicht unendlich viele Zustände, können vom Künstler, vom Ausstellungsmacher, vor allem aber von ihrem Besitzer mal in dieser und mal in jener Form gezeigt werden. Wer das will, kann der jeweiligen Arbeit täglich eine neue Form entlocken. Dabei kann er sich an Vorschlägen des Künstlers orientieren, kann aber auch Formen hinzu erfinden. Gibt es etwas Subjektiveres? Hat der Künstler mit einem solchen Konzept von Kunstwerk den Autonomiebegriff verraten? Hat er seine Arbeit zum Spielzeug eines Dritten degradiert? Die Antwort lautet nein.

Giuffridas Konzept beinhaltet zwar den Zugriff auf seine Arbeit, und es duldet auch das Entstehen von Variationen, die in ihrer äußeren Form dem Künstler vielleicht nicht recht sind. Aber das jeweilige Kunstwerk definiert sich nicht durch die Interaktion mit einem Dritten. Die Arbeiten sind nicht Hilfsmittel, um die kreative Entwicklung ihres Besitzers zu fördern. Und Spielzeuge sind sie schon gar nicht. Was Giuffrida viel mehr interessiert als die Interaktion eines Dritten mit einen Arbeiten, sind die Variationsmöglichkeiten an sich. Die verschiedenen Anordnungen der „Elemente“ oder der „Unsichtbaren Objekte“ decken das in den Kunstwerken innewohnende Potential auf. In einer konventionellen Arbeit, die das endgültige Ergebnis eines künstlerischen Prozesses darstellt, ist dieses Potential sozusagen versteckt. Es besteht aus den zahllosen Entscheidungen, die der Künstler während des Entstehens des Werkes treffen musste., in den Varianten gegen die er sich entschieden hat. Das Potential ist vollständig nur für den Künstler nachzuvollziehen, wenn er sich an alle Einzelentscheidungen überhaupt noch erinnern kann. Für den fremden Betrachter lässt es sich nur noch erahnen, denn es liegt in der Vergangenheit, ist Geschichte geworden. Anders die Arbeiten von Alfio Giuffrida: Hier hat sich der Künstler die Möglichkeit offen gehalten. Er muss sich nicht auf einen Endzustand festlegen, sondern hat den Weg gefunden, wie er mehrere anbieten kann. Ein Nebeneffekt ist, dass auch der Besitzer/Nutzer der Arbeit auf die Suche gehen darf.

Man mag vermuten, dass Alfio Giuffridas Interesse an Variabilität und Beweglichkeit auch aus seiner langjährigen Erfahrung als Bühnenbildner gespeist wird. Sind doch seine Bühneninszenierungen - überwiegend für das Tanztheater - gerade dadurch geprägt, dass sie mit einigen wenigen abstrakten Elementen auskommen, die - jeweils unterschiedlich positioniert auch verschieden genutzt - von Szene zu Szene neue, unterschiedliche Räume schaffen. Ähnlich wie dem Nutzer der „Elemente“ bietet Giuffrida dem Regisseur seine skulpturalen Versatzstücke auf der Bühne an. Wie bei den „Elementen“ sind damit gewisse gestalterische Grundformen festgelegt. Am Gesamterscheinungsbild, an der Atmosphäre ist nichts zu ändern, wohl aber an den Endzuständen. Zahllose Variationen sind möglich, aber der Rahmen, der nicht zu durchbrechen ist, wird durch den Künstler/Bühnenbildner vorgegeben. Sowohl im Theater als auch in der bildenden Kunst.

Eine weitere Besonderheit im skulpturalen Schaffen Alfio Giuffridas mag gleichfalls mit seiner Theatererfahrung zu tun haben. Giuffridas Arbeiten haben keine „logische“ Größe. Er gehört zu der nicht sehr großen Anzahl von Künstlern, die Werke schaffen, die man im Original sehen muss, wenn man wissen will, wie groß sie sind. Sie „funktionieren“ sowohl als Miniatur wie auch als monumentale Plastik. Der Blick auf ein Foto einer solchen Arbeit verunsichert, denn man muss schon genau hinschauen, um zu erkennen, in welchen Dimensionen der Künstler gearbeitet hat. Neben den „Unsichtbaren Objekten“ gilt das vor allem für die Plexiarbeiten, die Giuffrida mit Fundstücken - häufig aus Metall - kombiniert. Vor allem die Plexiarbeiten ähneln den Elementen, mit denen er im Theater arbeitet. Und ihre merkwürdige Eigenschaft, das Verstecken ihrer eigentlichen Größe, rührt wohl daher, dass der Bühnenbildner gelernt hat, mit Modellen zu arbeiten. Was einmal im menschlichen und manchmal übermenschlichen Maß auf das Theater kommt, wird zunächst kleinmaßstäblich entwickelt. Der Regisseur muss durch das Modell überzeugt werden, das Theaterpublikum durch die Inszenierung. Diese doppelte Herausforderung löst Alfio Giuffrida nicht nur auf der Bühne, sondern auch in der bildenden Kunst. Vieles - nicht alles - was er schafft, kann als Miniatur daher kommen, aber auch als Großplastik. Dem Kunstwerk wird dadurch Nichts genommen, im Gegenteil: Es gewinnt eine neue Dimension hinzu. Der Vergleich zu den verschiedenen Zuständen der „Elemente“ drängt sich auf. Giuffridas Kunst kennt nicht den einen endgültigen Zustand, sie ist auf Variabilität angelegt, ohne beliebig zu sein. Und in diesem Sinne widerspricht sie dann doch dem Diktum des großen Spötters Oscar Wilde. Natürlich spiegelt sie die Natur, denn auch die ist durch fast unendlich erscheinende Variationen geprägt, lässt vieles zu und ist letztlich doch durch Gesetzte gebunden. In diesem Sinne schafft sich Alfio Giuffrida sein eigenes Universum.

Text von GERT FISCHER

IT REALLY DEPENDS

Observations on the sculptural works of Alfio Giuffrida

As an exception (really an exception), let us start with a quotation: Somewhere towards the beginning of Oscar Wilde's Portrait of Dorian Gray, there is the sentence „Art does not imitate Nature, it imitates the observer.“ This sentence is extremely important as the story proceeds; it asserts the leitmotiv. The moral decay of the hero in the title is reflected in his portrait. The arch provocateur Oscar Wilde uses the sentence simultaneously to speak out against the appreciation of art at the time. Although inwardly he is in no way convinced by subjectivism, he adopts the pose and throws down the gauntlet to all those who, as artists and observers of art, have sold out to the exploitation of real Nature. He breaks a lance for the artificiality of art and questions the motives of those who want to draw close to the work of art in objective discourse. Such a stance continues to be provocative today, although, despite all the scepticism that exists towards the artistic theories of the 19th century, we stand by the autonomy of the work of art. Oscar Wilde questions this autonomy – we can also interpret his dictum as saying that art is only what the observer makes of it.

„Art does not imitate Nature, it imitates the observer“ could also be an initial insight – and only an initial insight – into a series of groupings in the sculptural work of Alfio Giuffrida. Examples such as his „Invisible objects“ from 1999 or „Elements“, which have appeared since 1997, are characterized by having no absolute form. Like a kaleidoscope, they have many, but not an infinite number of states, and can be presented by the artist, the exhibitor or, especially, the owner in a variety of forms. Anyone who wants to can coax a new form from a particular work on a daily basis. He can heed the artist's suggestions but can also discover additional forms. Could anything be more subjective? Has the artist, by employing such a concept, betrayed the autonomy of the artwork? Has he degraded his work to the level of a toy for a third party? The answer is no.

Giuffrida's concept embraces access to his work but also allows for the creation of variations whose external form may not sit well with the artist. But a particular artwork is not defined by interaction with a third party. The works are not an aid designed to boost the owner's creative development. And they are certainly not toys. What Giuffrida finds more interesting than the interaction of a third party with his works is the number of possible variations. The different arrangements of „Elements“ or „Invisible objects“ reveal the innate potential of the artworks. In a conventional work which represents the end result of an artistic process, this potential is more or less hidden. It consists of the innumerable decisions which the artist must face during the creation of the work in the variations which he has rejected. The potential is only fully realized for the artist if he can still remember all his individual decisions. The outside observer can only surmise because it lies in the past, having become history. But the works of Alfio Giuffrida are not like that: Here the artist has kept the options open. He does not have to stand by a final form but has found a way of being able to offer more. A side effect of this approach is that the owner/user of the work can join in the search.

One might suspect that Alfio Giuffrida's interest in variability and mobility is a product of his years as a stage designer. However, it is more a case of his stage productions – most of them for the ballet – being stamped with a few abstract elements which, each positioned differently and used differently, create new and innovative spaces from scene to scene. Like the user of „Elements“, Giuffrida offers the director his sculptural sets on the stage. In the case of „Elements“, this involves the establishment of certain basic, artistic forms – in the overall appearance, where nothing of the atmosphere is to change, as well as in the final positionings. Numerous variations are possible, but the framework which cannot be infringed is defined by the artist/stage designer. This applies in the theater and in the plastic and graphic arts.

One other feature of Alfio Giuffrida’s sculptural works may also be associated with his theater experience. Giuffrida“s works do not have a „logical“ size. He belongs to that small minority of artists who create works which must be seen in the original if one is to know how large they are. They „function“ equally as miniatures and as monumental sculptures. Looking at a photograph of such a work is unnerving, because one has to look closely to discover the dimension in which the artist has worked. This applies not only to "Invisible objects" but especially to the plexiglass works which Giuffrida combines with objets trouvés, often in metal. It is the plexiglass works in particular which resemble the elements with which he works in the theater. And their outstanding feature, the concealment of their actual size, indicates that the stage designer has learnt to work with models. What appears in the theater in human and, often, superhuman dimensions is first developed on a tiny scale. The director must be convinced by the model, the theater audience by the mise-en-scène. Giuffrida satisfies these twin requirements not only on the stage but also in his art. Much, but not all, of what he produces can start as miniatures but also as large sculptures. This does not detract from the artwork but rather brings a new dimension to it. It is tempting to make comparisons with the different positions of „Elements“. Giuffrida's art does not recognize a final state; it is based on variability without being arbitrary. And in this sense, it contradicts the dictum of that great mocker, Oscar Wilde. Of course it imitates Nature, because Nature, too, is characterized by an almost infinite number of different variations. It is very tolerant but is ultimately subject to laws. In that sense, Alfio Giuffrida creates his own universe.

Text von GERT FISCHER

Internet

Internet

offers / Requests offers / Requests  |

About this service |

|---|

Exhibition Announcements Exhibition Announcements  |

About this service |

|---|

Visualization |

Learn more about this service | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Interested in discovering more of this artist's networks?

3 easy steps: Register, buy a package for a visualization, select the artist.

See examples how visualization looks like for an artist, a curator, or an exhibition place: Gallery, museum, non-profit place, or collector.

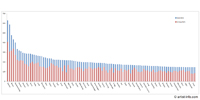

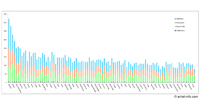

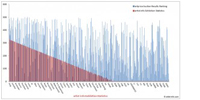

Exhibition History

|

SUMMARY based on artist-info records. More details and Visualizing Art Networks on demand. Venue types: Gallery / Museum / Non-Profit / Collector |

||||||||||||

| Exhibitions in artist-info | 4 (S 3/ G 1) |

Did show together with - Top 5 of 406 artists (no. of shows) - all shows - Top 100

|

||||||||||

| Exhibitions by type | 4: 0 / 2 / 2 / 0 | |||||||||||

| Venues by type | 4: 0 / 2 / 2 / 0 | |||||||||||

| Curators | 0 | |||||||||||

| artist-info records | Mar 1975 - Aug 2004 | |||||||||||

|

Countries - Top 2 of 2 Germany (3) Italy (1) |

Cities 4 - Top of 4 Siegburg (1) Mannheim (1) Aachen (1) Roma (1) |

Venues (no. of shows )

Top 4 of 4

|

||||||||||

|

Curators (no. of shows)

Top 0 of 0 |

| Mannheimer Kunstverein | S | Jul 2004 - Aug 2004 | Mannheim | (86) | +0 | |

| Stadtmuseum Siegburg | S | Apr 2001 - Jun 2001 | Siegburg | (78) | +0 | |

| Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum Aachen | S | Feb 2001 - Apr 2001 | Aachen | (49) | +0 | |

| X Quadriennale Nazionale d'Arte | G | Mar 1975 - Apr 1975 | Roma | (5) | +0 | |

| Keep reading |