FROM THE ARCHIVES OF AMERICAN ART: THE ROLE OF THE MACBETH GALLERY

October 1962 - May 1963

The American Federation of the Arts

41 East 65th Street, New York 21

ANNOUNCEMENT.

I respectfully call attention to the fact that I have leased the store No. 237 Fifth Avenue for the permanent exhibition and sale of American pictures, both in oil and water colors.

The work of American artists has never received the full share of appreciation that it deserves, and the time has come when an effort should be made to gain for it the favor of those who have hitherto purchased foreign pictures exclusively. As I shall exhibit only that which is thoroughly good and interesting, I hope to make this establishment known as the place where may be procured the very best our artists can produce. An experience of over eighteen years in the picture business will be devoted to the accomplishment of this result.

The location, two doors above 271h Street, is in the immediate neighborhood of the large hotels, and easily accessible from every part of the city.

Visitors will be welcome at all times.

WILLIAM MACBETH.

New York, April, 1892.

THE ROLE OF THE MACBETHGALLERY

Of all the participants in the life of the arts, the art dealer gets the worst press, if he gets any press at all. When he appears on the stage or in books itis usually as a character with as little conscience as the villain in the old-fashioned melodramas. Yet everyone who has been in the art world, in any capacity, knows that the art dealer plays an important role; that it is, in effect, impossible to ignore his contributions. Ignored they are, none-the less.

The Archives of American Art has been given: the papers of the Macbeth Gallery, covering the more than sixty years of its activity in New York City. A selection from these, and from the pictures sold by that gallery, have been assembled by the staff of the Archives and of The American Federation of Arts, with the advice of Mr. Robert G. McIntyre, the last president of the Gallery, and is here presented. The exhibition will we hope make clear, through the long and distinguished record of that gallery, something of what the role of the art dealer is. He makes, as I see it, three main contributions beyond his role as a merchant of quality: by helping the artist to find his audience, he opens the road to reputation and success for the talented; by maintaining a standard of quality he educates collectors and the public, and so helps to shape taste; by rescuing works of art from obscurity and bringing them to attention, he saves them from destruction and thus helps preserve our artistic heritage. Three men headed the Macbeth Gallery. Each played his own role yet their different careers illustrate all of these functions.

William Macbeth (1851-1917) came to the United States from Ireland in 1871 and began his career with Frederick Keppel and Co., print sellers. In 1892 he opened the Macbeth Gallery at 237Fifth Avenue, the first gallery at that time to deal solely in American art. He encouraged a number of the younger men and was helpful in establishing the reputations of painters like Arthur B. Davies and Robert Henri. The most famous of his exhibitions was that of The Eight, in 1908, which commenced a new period in our art. He established his own publication, Art Notes, a combination of house organ and running commentary on the artworld, and edited it until his death.

Robert Macbeth (1884-1940), the son of William Macbeth, joined the firm in 1909 and became president in 1917. He established the Gallery as one of the leading firms in New York, showing both contemporary and older American art, and in 1928 was instrumental in organizing the American Art Dealers Association, serving as its first president.

Robert McIntyre, the nephew of William Macbeth, had joined the firm in 1903 and became president on the death of his cousin in 1940. He continued the Gallery's tradition of showing both the work of living American artists and American artists of the past. His standing was more than that of an art dealer; he was an adviser to museums and a scholar whose book, for example, on Martin Johnson Heade is still the only monograph on this rediscovered artist. He closed the Gallery in 1953 and when the corporation was finally dissolved in1957, turned over its records to the Archives of American Art.

The Archives of American Art, founded in 1954 as a national research institute, has from the first set out to document the art world as a whole. This meant that it has set out to preserve and make accessible to students, the papers of:

1. Artists and craftsmen of all kinds, of every period of our art.

2. Collectors.

3. Dealers.

4. Critics and historians.

5. Museums, societies and institutions of art.

Its collection consists of original and secondary source material (MSS., letters, notebooks, sketch-books, clippings, exhibition catalogues, etc.); other printed material, such as auction sales catalogues, publications of societies, all types of rare and out-of-print material; microfilms; and photographs of works of art. We are grateful to Mr. McIntyre for his wisdom in securing the preservation of the records of the Macbeth Gallery, which form a major contribution to the history of American art in modern times. We are grateful also to The American Federation of Arts for its recognition of the role of the Macbeth Gallery and for assembling this exhibition with its accustomed skill and care; to the trustees and staff of the Archives who worked on this exhibit, notably Mrs. Otto L. Spaeth, Mr. W. E. Woolfenden, and our two archivists, Mrs. Miriam L. Lesley and Mr. Garnett McCoy. Their joint efforts have created an exhibit that tells a story worth our attention and thought.

E. P. Richardson

Director,

Archives of American Art.

THE MACBETH GALLERY: A CAPSULE HISTORY

In April, 1892, my uncle, William Macbeth, I who for many years before this was associated with Frederick Keppel, an internationally known dealer in rare prints and a recognized authority in the field, sent the following announcement (deleted here in part for lack of space), to the press: "I respectfully call attention to the fact that I have leased the store, No. 237 Fifth Avenue, for the permanent exhibition and sale of American pictures ... The work of American artists has never received the full share of appreciation it deserves, and the time has come when an effort should be made to gain for it the favor of those who have hitherto purchased foreign pictures exclusively... I hope to make this establishment the place where may be procured the very best our artists can produce. .".

Since, in 1892, foreign art, particularly the Barbizon and Dutch schools, still held sway here, and since William Macbeth had ventured into the business of selling American art against the advice of his most intimate friends who disclaimed any such cultural distinction for America and, too, since this was a panic year, the above announcement was, to say the least, somewhat rash! But it was made by a man of vision who lived to see his strong faith fully justified. The first few years were almost disastrous, with little prospect of better times for himself or for the American artists he hoped to promote.

Until this time, the relatively few buyers of American pictures visited the artists' studios, or bought from the National Academy exhibitions; there was no dealer's gallery where their work could be seen at all times. The new venture was intended to fill this need. Gradually, as conditions improved, this small gallery became a convenient stopping place where, on Saturday afternoons (the day for looking at pictures), collectors, curious to see if contemporary American art had any merit, could, at their ease, have a look. Too often this cost them nothing! With the strong competition of foreign art, and the favorites among the older established American painters, Inness, Homer and possibly Ryder, for example, the younger generation had a rough time of it. (I must mention here the notable exception to the general opinion that American art was not of much account; Thomas B. Clarke held a different view and was far from timid in expressing it. Beginning in the '70's, he made the rounds of the studios, and many an artist received encouragement as well as profit from these visits. He purchased judiciously and generously, was the first to realize the genius of Inness and Homer, the first to show a buying interest in the "younger painters," as he called them, and the first to form a large collection of exclusively American art. He and William Macbeth had many a chat on the present and future state of native art. In 1899, he sold his collection consisting of 372 pictures by 167 artists, many of them young when he first bought their work.)

In addition to this predominantly foreign taste the contemporary artists had to face there was still another reason why Macbeth had such difficulty in getting started. It is well to remember that many years previous to this American art had been much in demand especially here in the East, and that such artists as Church, Cole, Durand, Whittredge, Bierstadt and others of the so-called Hudson River School, became financially very prosperous from the sales of their pictures. This was in the Civil War era and for some time afterward. Business men-merchants, wholesale grocers, railroad builders and the like, becoming very rich, enhanced their social status by spending large sums of money on pictures. They lived in city mansions with unlimited wall space, and the bigger the picture the greater the glory. But they loved their pictures, too, and many of them took a personal interest in their favorite artists, and helped them in other ways as well.

But time, in its inexorable processes of screening and re-screening, changed all this and, as a consequence, pictures by these once so popular artists could be had, when wanted at all, for a mere song, while the artists themselves sank deeper and deeper into the shadowy twilight. Thus, by the time Macbeth had arrived on the scene, the once lush pastures of an earlier day had shrivelled up while fresh ones were slow to develop. It was as if he had stepped into a vacuum with little but his own vision and fortitude to fill it.

In time, however, taste, slowly changing, did improve the outlook somewhat for both dealer and artist, but it still was an uphill struggle. Especially was this so for those artists dissatisfied with the emptiness of the status quo in the current academic, sterile expression; who were striving to develop their own individualities into a personal and independent approach to art and what seemed to them to be its function. Mere superficial appearances were not enough; there was something more, something deeper; however indefinable this might be, they wanted to find it, to experience it each in his own way. And so, it was that men like Theodore Robinson, Twachtman, Weir, Hassam and a few others, still fairly young at the time, found their way fraught with discouragement and disappointments through lack of appreciation. They were "radicals," violating all the tenets of a hallowed and well entrenched tradition.

And then, somewhat later, along came, of all things, the "Ashcan School"! And its attendant fury! Henri, Sloan, Luks, Glackens, Shinn, Davies, Lawson, Prendergast, the men, particularly the first four, who for years had been consistently agitating against the genteel, sentimental, salon-type painting ever present in the Academy exhibitions. They were the uncompromising, outspoken realists who came to grips with life in the raw, who felt that the seamy side, as lived in the Bowery, the Haymarket, and other "horrid" places, was just as real, even more so, as the luxury of a Fifth Avenue drawing room. So, for a long time they suffered for their impudence and effrontery, their direct insult to the artistic sensibilities of the collectors of the day. So, too, did Macbeth.

When, in 19o8, he gave this group, calling themselves "The Eight," their one and only "annual" exhibition, he received threatening letters, phone calls, and visits, mostly to the effect that "if this is the kind of art you are going to sponsor, cross us off as clients." I mention this incident because of its amusing sequel. In the mutations of time which indulges in strange and unexpected happenings, a number of these self-same, outraged protestants bought into the "Ashcan School"! (and loved it!). When the sound and the fury had died down, or at least were greatly modified, as the idea that art is something that does not stand still gradually entered the consciousness of art lovers and collectors, these radicals became "respectable," even if not wholeheartedly accepted. William Macbeth, too, profited by the changing atmosphere. And if in later years he ever ruminated on the vicissitudes of his career as an art dealer after he had become at least moderately successful (he died in 1917), it must have been with a good deal of satisfaction, and not a little amusement, having in the very beginning been warned against the futility of promoting American art which to so many at the time was a non-existent quantity; then taken to task for his sponsorship of what later became known as the American Impressionists; and, finally, soundly berated for standing solidly back of the "Ashcan School."

Before bringing this capsule history of the Gallery to a close, I should like to mention that though Macbeth's interest was primarily concerned with contemporary art, he was also interested in another phase of American art-the late i8th and early r 9th century portrait painters. He was a close student of this period, traveled extensively throughout New England and the South, and was active in developing collector interest in this important school.

Though this exhibition evokes within me many nostalgic images, recreating past experiences, I think of it, not so much as the role in American art played by the Gallery itself, but, rather as a personal tribute to the original vision and idealism of its founder, William Macbeth. During the many years I was associated with him, I was witness to this vision, this idealism. I am deeply grateful for this tribute.

I am grateful, too, to Dr. Edgar P. Richardson, scholar and humanist, who developed this idea with The American Federation of Arts; and to The American Federation of Arts for its ready and willing cooperation in assembling it and circulating it through various art centers; to the many museum directors, trustees and private owners who ungrudgingly lent the pictures that have made the exhibition possible; to Bill Woolfenden of the Archives of American Art; and last, but by no means least, to Miss Virginia Field, Miss Diane Goetz, Miss Margaret Cogswell, for their untiring and, I suspect, sometimes arduous efforts.

R. G. McIntyre

October, 1962

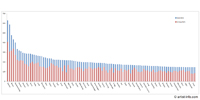

artist-info Exhibition Id

https://www.artist-info.com/gallery/Macbeth-Gallery

https://www.artist-info.com/exhibition/AFA-Id391598

https://www.artist-info.com/exhibition/AFA-Id391599

Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries. Thomas J. Watson Library Digital Collections

Exhibition Announcements

Exhibition Announcements