Exhibition of Russian Painting and Sculpture

February 24 - April 06, 1923, Brooklyn Museum (NY)

Foreword by William Henry Fox

Introduction by Christian Brinton

Foreword

While the war left in its wake much to deplore, it had one happy result for this country. It brought to us the products of European culture in volume and richness hitherto undreamed of. Since 1914, the Brooklyn Museum has afforded the opportunity of placing Europe's best contemporary art before the New York public. Sweden, France, Switzerland, and England, have successively exhibited in these galleries the work of their most talented artists. Again a rare privilege is placed within reach of the American public. For the first time is Russian art shown in the United States in anything approaching its true strength and unity. In the current exhibition, twenty-three [twenty-four] artists have united to show their work side by side for the purpose of indicating to the American people the significance of contemporary Russian art. The Brooklyn Museum has the honour to welcome these disinterested pioneers, and to thank them for their gracious co-operation. The Museum likewise tenders grateful thanks to the French Government, to Mr. Edward Duff Balken, Mrs. George Blumenthal. Mr. Robert Winthrop Chanler, Mr. William Astor Chanler, Mrs. Clarkson Cowl, Miss Elsie de Wolfe, Miss Katherine S. Dreier, Miss Helen Frick, Mrs. John W. Garrett, Mr. Morris Gest, Mr. Raymond Henniker-Heaton, Mr. John R. Hunter, Mrs. Otto H. Kahn, Mrs. Thomas L. Leeming, Mr. Adolph Lewisohn, Mrs. Philip Lewisohn, Mrs. Benjamin Moore, Mr. James N. Rosenberg, Mr. Robert Schwarzenbach, Mrs. Elise, M. Stern, Mr. William S. Stimmel, Mrs. William K. Vanderbilt, Mrs. Efrem Zimbalist, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Worcester Art Museum, the Société Anonyme, the Kingore Galleries, M. Knoedler & Co., the New Gallery, and the Galleries of Mrs. Albert Sterner. To Dr. Christian Brinton the Museum expresses grateful appreciation of valued assistance, and for the notable catalogue of the exhibition, with cover design by Vadim Chernov.

William Henry Fox [Director Brooklyn Museum]

Introduction

By Christian Brinton

Il n'y a pas de style Russe; il y a l'âme Russe

Transported to us upon the magic carpet of circumstances, exotic of aspect and passionate in appeal, is the current display of Russian painting and sculpture. Whatever else it may achieve, Slavonic aesthetic expression offers a vivid epitome of the national consciousness. A thousand years of shifting pageantry, the successive ascendancy of influences now Byzantine, now Mongolian, now frankly European, have altered the outward semblance, but not the inner Spirit of Russian art. Emerging from an austere, hieratic, or sumptuously boyarian Background, Slavonic painting and sculpture look toward a future not less eloquent or less typical.

The art that unfolds itself before us upon these walls is strictly contemporary. Though its roots sink deep into the ages, this work is of to-day, and fully reflects actual conditions and tendencies. Despite the tragic vicissitudes of the last few years, each of the exhibitors is still living, and several of them have fortunately reached our shores. You thus have before you not Russian art in retrospect, but Russian art as it is currently seen in Moscow, Berlin, Venice, or Paris. The magic carpet that bears the plastic and colouristic message of Russia around the world, has for the moment descended into our midst.

Modern Russian art begins, you doubtless recall, with the secession from the Imperial Academy, in 1863, of an aspiring band of radicals headed by Ivan Kramskoy, who rebelled against the sterile formalism of routine instruction, and demanded more vital themes from which to work. Within the ensuing decade they organized a thriving society known as the Peredvizhniki, or Wanderers, and carried their programme triumphantly throughout the country. Realism, and an ardent nationalism were their watchwords, and for a generation their position remained unchallenged.

The foremost exponent of Russian realism is the masterful Cossack, Ilya Repin, and in a measure the mantle of Repin has descended upon the shoulders of one of his favourite pupils, Nikolai Fechin. In its essential features the art of Fechin is Repinesque. Yon note in these portraits and character studies from the picturesque, semi-Tatar district about Kazan, provincial types in all their primitive verity. Fechin in fact came from Kazan, and it was to Kazan that he returned after his prentice days at the Imperial Academy to depict that life and scene for which he evinces such abiding sympathy.

During the years when Fechin pursued his studies at the modest art school in his native city, and passed the summer months sketching in remote, outlying village, there used to forgather at the home of Alexander Benois in the Oulitza Glinki, a coterie of artists and intellectual aristocrats to whom the name of Repin was anathema. They abhorred realism. They betrayed scant love for peasant or proletarian, and passed unforgetable nights in feverish discussion, or strolling along the Neva quays singing arias from Tchaikovsky's Queen of Spades, while the chimes from the cathedral tower of St. Peter and St. Paul sonorously chanted the hours. The sensitive, penetrant intellect of the group was Benois himself, its dynamic impetus derived from Diaghilev, and its chief artistic asset was the ever facile and fecund Bakst. They perforce had to have their medium of publicity, and in due course appeared Mir Iskusstva, the early issues of which contained a series of spirited onslaughts upon the excessive xenphobia and provinciality of the day.

To the undying disgust of Stasov and the old guard, Mir Iskusstva, and the art exhibitions organized under its auspices, exalted that which was exclusive, eclectic, and European rather than Slavic. "We are a generation hungry for beauty," proclaimed Diaghilev, and beauty they discovered in the sophisticated eroticism of Somov, the rococo irreality of Lanceray, and the delicately traced vignettes of Dobujinsky. Led by Benois, who had lived at Versailles, they were one and all retrospectivists. They harked back to Sèvres and Saxon figurine, to the Empire, Louis Seize, Peterhof, the shaded seclusion of Pavlovsk park, and the picturesque and appealing charm of Old St. Petersburg. They did their best, in short, to disguise, to de-Russianize themselves.

Yet the consuming energy and ambition of Diaghilev proved the salvation of Mir Iskusstva, and of these young dilettanti from the College May. Relinquishing the review, which had proved a costly adventure, Diaghilev turned his attention to the stage, where he proceeded to fulfill his destiny as the supreme artist-impressario of theatrical history. Decorators rather than painters, the members of Mir Iskusstva likewise achieved their chief successes in scenic production. Here Bakst disclosed the passionate splendours of Cleopatra and Scheherazade, Benois the poignant fantasy of Petrushka, Anisfeld a luxuriant chromatic imagination, and Roerich the smouldering intensity and dramatic suspense of the Polovetzky Stan scene from Prince Igor. When Diaghilev raised the curtain upon the initial representations of the Ballet Russe at the Châtelet in 1909, he revealed to Western eyes a new art form. The exhibition of Russian painting seen at the Grand Palais three years previously, failed to enthuse the Parisian pubic as did the sudden apparition of the Ballet Russe. Here was a veritable synthesis of the arts - fresh, daring, replete with plastic and colouristic fervour, and fused by a truly creative imagination into a single, organic ensemble.

A salutary antidote to the general spirit of Petrograd preciosity, which lingered like a frail blossom on the brink of an abyss, was shortly found in mellow, full-flavoured Moscow. If Petrograd is classic and apollonian, Moscow joyous, vital, and genuinely dionysian. It was at the private theatre of the private theatre of the prince Mamontov, a veritable Muscovite Metzenat, that latter-day Russian stage décor first came into being, and it was in this same fruitful atmosphere that contemporary Russian painting received its most significant-stimulus. Vrubel it was who flung his resplendent, demon-haunted fantasy against the dull reality of the Peredvizhniki, and in the train of Vrubel and his Swan Princess followed Korovin, the sumptuous colourist, Aleksandr Golovin, and a score of Iesser lights. The drift away front actuality was synchronic. For, just as the flaming vision of Vrubel soon overcast Repin and the realists of brush and palette, so the conscious scenic artistry of Meyerhold marked a similar reaction against the zealous illusionism of Stanislavsky and his colleagues of the Khudozhestvenny Teatr.

The first decade of the present century in Moscow was a period of inspiring ferment. While a few of the local artists were admitted into the rarefied ranks of the Mir Iskusstva, the majority remained faithful to the Soyuz, or banded together in rebel groups and under frankly insurgent banners. They welcomed the French modernists long before their Petrograd brethren were aware of their existence, and it is impossible to overlook the influence upon the present generation of Moscow artists of such epoch-making figures as Cézanne, Gauguin, van Gogh, Henri-Matisse, Picasso, and the Futurists.

Led by the ardent progressives, Larionov, Goncharova, Gonchalovsky, Tatlin, and Burliuk, the younger set employed the most rudimentary tactics in order to place themselves and their theories before the public. Larionov paraded the Tverskaya arrayed in cubist costume while the dynamic Burliuk displayed his canvases on street corners, to the accompaniment of eloquent explanatory comments by himself. Various societies such as the Blue Rose, the Target, the Donkey's Tail, and the Bubnovy Valyet, or Knave of Diamonds, sprang into being, the latter surviving the rest and commanding most consideration and support. It was all vastly different from formal, patrician Petrograd, but despite a deal of gratuitous clamour, the participants were sincere, and possessed of unquestioned talent.

The real spirit of Moscow was not, however, reflected in such sporadic manifestations. .And just as Petrograd, the "Palmyra of the North," discloses in Leon Bakst an epitome of suave, sensuous neo-Hellenism, so in Sergei Sudeykin Moscow has produced an artist who depicts as none other the geniality, the gusto, and the inextinguishable love of life that typify the city by the Moskva. Yet the art of Sudeykin, like that of Bakst, is retrospective in spirit. It glances back to the picturesque period of 1830 and 1840, to Gogol and to Ostrovsky. And now and t hen, with a passion and imagination which bespeak the poet that lurks at the heart of every genuine satirist, it reaches toward the sumptuous realm stretching away to South and East — the land of Gipsey, Georgian, and Bashkir. The pageant of Russian art reveals nu more characteristic figure than this same diverting Sudeykin, of whom Benois once said, "il est venu au monde en dansant."

Possessing such a heritage racial and aesthetic, it is scant wonder that the Russian artist should feel impelled to draw upon his incomparable native patrimony. The remote, austere varengian, Nikolai Roerieh, leads us magically back to the pale half light of history. Natalia Goncharova and Vadim Chernov evoke for us the mystic spirit of saint and apostle, which gleams from ikon or the frescoed wall of cathedral and monastery. And Larionov, once he lays aside a doctrinaire modernism, delves into the treasure-troves of popular fancy, bringing forth, as in his Contes Russes, images that real more than all else the creations of the genial fabulist Krylov. The sheer fecundity of these artists is amazing. They discover effective motifs anywhere and everywhere — at rural .fêtes and fairs, in the quaint signs of provincial shop and traktir, and the crudely tinted toys of simple peasant child. In some guise or other this varied and vigorous stream of form and colour finds its .way into the more conscious production of the professional artist. And it is Ute Moscow painters who most fully appreciate its essential beauty and validity. For Moscow has ever remained closest to the national ideals, and the creative aspirations, of the great mass of the Russian people.

The achievement of the foregoing men and their colleagues of brush and chisel brings our slender survey of contemporary Russian art down to the beginning of the war and the consequent dissolution of the old order. The period from the formation of the Peredvizhniki to the advent of the Mir Iskusstva, and the more virile and autonomous Moscow group, was, as we have noted, a period of sober, pedestrian endeavour. The decade that extended from the Russo-Japanese war to 1914 was characterized by a passionate quest of beauty, and an unparalleled florescence of creative and colouristic fancy. And while it was Diaghilev and his Ballet Russe who first captured the enthusiasm of the Western world, Russian painting as such had won its right to be considered upon, its own merits quite apart from the lustre it lent to opera and choreodrama. Comprehensive as was Diaghilev's exhibition at Paris in 1906, it proved but a prelude to that which was to follow.

The arrival of the war and the dislocation of forces political, social, and economic, wrought rapid changes in the physiognomy of Russian art. Following the outbreak of the revolution, a number of painters and sculptors fled the country to seek refuge abroad. Paris and Berlin claimed a goodly quota, and are still gaining fresh recruits. Our own first visitor was Boris Anisfeld, who crossed the Trans-Siberian and reached us early in 1918. Anisfeld was followed by Roerich, who had paused en route in Finland, Sweden, and England, and was met on the dock by his friend, Derujinsky, but lately landed from the Black Sea Port of Novorossysk. With the fall of the Kerensky government, there began an exodus of the Russian intelligentsia that may be likened to the departure of the Italian artists for France during the later Renaissance, or the migration of the Saracens to Spain. Only those of sturdy temper or aspiring expectancy, such as Burliuk and Boris Grigoriev, elected to remain in Russia, and they, too, subsequently turned their faces, one to East, the other to West.

The three artists of the present exhibition in whose work you can discern traces of the social and political cataclysm that has overtaken their country are Burliuk, Grigoriev, and Manievich. Each lingered within the red flare of the Terror, and each has recorded his impressions in characteristic fashion — Burlitik modernistically, Grigoriev humanistically, Manievieh with a touch of imaginative synthesis. While the reaction of the revolution upon the sensibilities of Burliuk and Manievieh was but transitory, in the case of Grigoriev it sank deeper into the well-springs of his creative consciousness.

With a vigour of statement that recalls the Italian primitives — a rigour of line and an integrity of purpose that suggest Matteo di Giovanni or Mantegna — Grigoriev pictures for us in n series of unforgetable panels life as he witnessed it in Sovdepia. There is indeed a phantasmal quality to the painting entitled Visages Russes that suggests some strange apocalyptic vision, a tortured memory, an hallucination. As a product of Bolshevist Russia the canvas has no parallel in art, and in literature can only be compared to Blok's Twelve. And yet Grigoriev is not exclusively an apostle of that ruthless reversion to type of which Blok, Bely, and Mayakovsky are notable examples. In his less stressful moments his outlook is serene and truly kindliche. Despite its frank eclecticism, its restless range from Mantegna to Montmarte, from primitive to neo-cubist, the basis of Grigoriev's art lies in its sound and superb draughtsmanship. The man is a master of graphic expression. His colouring, which, for the most hart, is the clear-toned mujik colouring he so loves, is merely suggestive. His triumph lies in his command of line and in his innate plastic power.

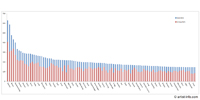

Creative activity in Russia, as elsewhere, oscillates with approved regularity between conservatism and a salutary modernity. White in the tempestuous cubo-futurism of Burliuk, and that hint of social mysticism you note in the canvases of Grigoriev, we have indications of profound unrest, the more acute products of Russian radicalism have not yet reached our shores. Larionov and Goncharova we already know. Paris is familiar with Chagall, but Tatlin and "tatlin-ism," Casimir Malyevich and "suprematism," together with the work of Kamyensky, Rodschenko, Kulbin, Falk, Olga Rosanova, and Lentulov, do not find place in the present Brooklyn Museum exhibition. Thus far in fact, they have not pushed beyond the Gallery van Diemen in Berlin [https://www.artist-info.com/blog/berlin1922], and recent issues of Jar-Ptitza.

The corrective to this latter-day experimentation, much of which in itself is obviously sociological as well as aesthetic, is however found in full strength upon these walls. Despite a congenital freedom of temper, even Grigoriev betrays elements of conservatism, while in the work of Jakovlev, Shukhaiev, and Sorin, we revert to standards that are frankly academic. As familiar with Cézanne as they are with Cimabue, with Picasso as they are with Pisanello, these young men have elected to pursue the pathway of moderation, not to say reaction. Former pupils of the Imperial Academy, they perpetuate the traditions of that imposing institution on the Vassili Ostrov, the portals of which were but recently dosed after a century and a half of organized activity.

Severe, disciplined, synthetic, and basing itself upon a deep-rooted reverence for form, the art of Jakovlev leans now to the static calm of the Orient, now to the serene naturalism of the Florentine primitives. Almost as painstaking in its fidelity to what may Ire termed the essential probity of visual representation, is the work of Shukhaiev, while Sorin suggests the complex psychology of the modern woman with a lineal beauty and surety recalling the baffling impeccability of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Distinctly post-revolutionary, the work of these latter men points toward that New Idealism which, in Russian literature and music as well, has begun to cast over a sorely troubled world its reassuring rays.

Whatever its deficiencies, the present display of Russian artistic activity is not lacking in variety of interest or inspiration. To the foregoing names may be added those of the young Georgian mystic and neo-orientalist, Lado Gudiachvili, the Parisianized Feder, the accomplished draughtsman and decorative scenic artist Nikolai Remisov, and the sculptors, Arkhipenko, Derujinsky, Patlagean, and Sudbinin, in whose work we encounter the same individual play of creative forces as in that of the painters.

Realistic, naturalistic, idealistic, stylistic, or fanciful and extramundane, Russian art, graphic or plastic, possesses certain specific points in common. It evinces, in particular, a pronounced hypostatic accord between art and life. The transition from one to the other is accomplished with perfect ease and spontaniety. A marked sensibility of temper characterizes Russian artistic activity. First, last, and always, these Slavs are emotional, and their art displays above all an organic emotionalism that nothing seems to efface. The art of France shows the dominance of intellect over Imagination; that of Russia illustrates the ascendancy of imagination over the intellect. In its every aspect Russian art epitomizes the eternal struggle toward freedom through sublimated creative expression. And the significant qualities of Slavic aesthetic aspiration an' its conviction, and its power to convince. It beckons eloquently toward that kingdom which all seek, that radiant realm — où tout y est vrai, bien que rien n'y soit réel.

Source: Catalog of this exhibition

artist-info.com Exhibition Pages

'Russian Painting and Sculpture (1/2) - Paintings and Drawings'

https://www.artist-info.com/exhibition/Brooklyn-Museum-of-Art-Id380375

'Russian Painting and Sculpture (2/2) – Sculpture'

https://www.artist-info.com/exhibition/Brooklyn-Museum-of-Art-Id380376

Exhibition Announcements

Exhibition Announcements